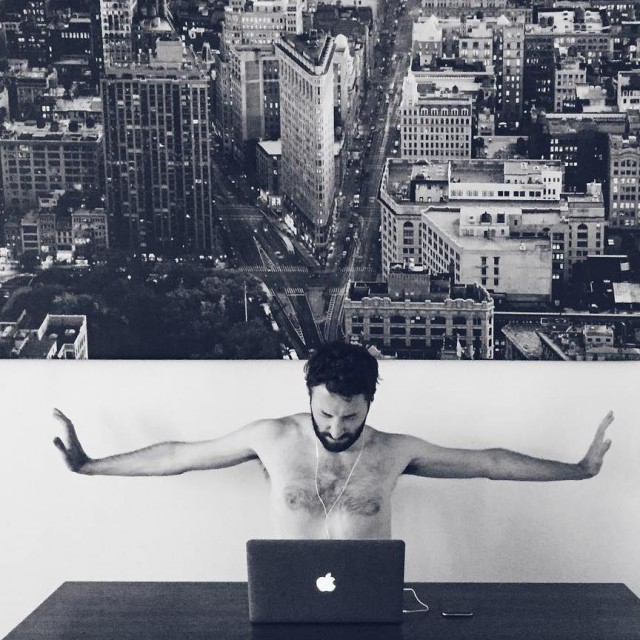

Photo by Francois Laforgia

Photo by Francois Laforgia

Ross Hammond and the Tao of Improvisation

At this year’s SXSW, Ross Hammond, performing with Teakayo Mission, put his rockist touch on the traditional hymn, “Let Us Go Into the House of the Lord,” leading a 14-minute tour of the heavenly kingdom. The live recording sounds as though he and his band mates reached nirvana; but for Hammond, this was just another night of performing in one of his many side projects.

It is tough to say why I feel this way, but the guitar has always been a spiritual instrument in my mind. Perhaps it is images of Jimi Hendrix kneeling in a prayer position, conjuring flames from a burning broken instrument, or the intoxicating feelings that come from Eddie Hazel’s 10-minute guitar soliloquy on Funkadelic’s “Maggot Brain.” A guitar is especially powerful when improvisation is introduced, allowing a guitarist to operate on instinct and inspiration—it is in these delicate moments that musicians seem touched by a divine muse.

Pulling the pomp from these circumstances, such musings can be reduced to just another good night for improvisational jazz—a scene that is garnering some attention in Sacramento. Ross Hammond has been operating within the limitless art form for over a decade, dividing time between improvisational groups, working as a sideman for singers and songwriters, teaching private lessons and curating local jazz shows. Some of his current projects, whether as a leader or session player, include RACE!!!, Teakayo Mission, V-Neck, Lovely Builders and Joaquin’s Night Train. Even with such a prolific resume, he’s reluctant to be dubbed torchbearer for the scene. “A lot of these projects that I’m playing in aren’t mine,” Hammond said. “There’s a lot of passing the leader title around in different projects. Usually a new project is from meeting someone new that’s into a similar idea or finding a new concept about how to present your music.”

Even in the most possessed thralls of improvisation, an artist cannot reach this higher ground without an intense dedication to the craft and community—one monk can’t run a monastery. Hammond views his eagerness to continually invite new musicians into his circle part of this ideal. “Playing with all kinds of different musicians and styles keeps you sharp,” he said. “That’s really the whole idea, in being able to play as much as I can in as many styles as I can.”

Hammond’s predilection for an unabashed marriage of style and technique are the principles for his latest solo record, An Effective Use of Space, a title penned by his wife. “It’s a phrase [she] likes to use when we talk about how things should be arranged in our house,” he said. “I’m sure someone could make a good musical meaning for it too. But it was more of a title that was given after the fact.”

Essentially, his wife has unwittingly helped this writer do just that, as his album suggests jazz feng shui. In a traditional sense, feng shui is an ancient Chinese system of aesthetics for improving ones life through placements of positive energy, but Hammond’s feng shui comes from his guitar-plucking intuition. The record also features several stylistic choices that require delicate placement.

[audio:Heaven Was Getting Crowded.mp3]Hammond occasionally deviates from his signature sound to pose dedications to friends and family. One of his favorite songs is “Heaven Was Getting Crowded,” which features his recently departed grandmother—Hammond recorded her delivering this joke during her final stay in the hospital. “I wanted to get a recording of her telling her favorite joke, so that’s pretty much how it came out,” he said. “She was a very loving and supportive lady, and she loved to make people laugh. She would tell us and the doctors and medical staff jokes up to her final days.” Without overshadowing the recording, he supports his grandmother’s joke with a bittersweet mood created from solo electric and lap steel guitar loops. “The song is meant as a way to remember her jovial side,” he said.

Once again, I recall Hammond’s SXSW recording. It is as though his guitar is in deep meditation, yet there’s an unspoken connection with his band mates. The spiritual is the constant, while the exploration of a deeper understanding is ritually being sought throughout the performance. “I try to communicate whatever I’m feeling in the moment,” Hammond said. “That obviously has some day to day changes, but there are some parts of my personality that are pretty much constant.” Originally from Lexington, Ky. and raised in the church, Hammond’s spirituality is connected to his guitar playing. “I think most improvisers are that way,” he said. “You should be able to get an idea of what a person is feeling by listening to them play. I think that’s what keeps improvised music honest. But there’s also the factor of what your other band mates are doing. So, it is definitely a balance of trying to get across what you feel while still listening to what’s going on around you.”

The practice of meditation in Eastern religions holds relevance to the improvised jazz performer. Obtaining Zen through meditation involves intense mental stamina as a person directs awareness toward breathing or counting until he or she establishes a trance state. Improvised music shares principles with meditation, as the beat is the groundwork for the journey that comes from reacting to your group and the impulses you feel in the moment. “It’s like you are an antenna that is channeling the music from somewhere else,” he said. “When I play, I’m definitely not thinking about scales or keys. There’s an old adage that says if you are thinking when you play, then you’re gonna muck it up.” Once again, Hammond likened it to his personal experience of participating communally in church, “I think that is a very spiritual thing, because in that sense the music is something that is bigger than just me and whoever I’m playing with. It’s definitely greater than the sum of its parts. I think it’s a similar feeling as being in church, or meditating or whatever else people do to escape. When you are improvising it’s a timeless feeling in that it’s hard to tell if the song you just played was five minutes or 45 minutes.”

Hammond stresses that, though time loses its relevance while performing and the transcendental progression is intoxicating, it is important to hold dear to your purpose. For Hammond, creating is far beyond notes on staff paper, matching scales to chords and counting beats. He spoke with restraint, worried he’d sound too “new age-y,” relating that he created “to convey a sense of unity and harmony in the world we live in.”

Finally, I asked Hammond if he thought his style of improv-jazz was less intimidating than most jazz because of its focus on the guitar and crafting soliloquies. He resisted my hypothesis stating, “I don’t see jazz artists like John Coltrane or Pharoah Sanders being that much different than Pete Seeger or Bob Dylan,” he said. “They are all trying to convey a message through their music. That’s the important part. I think at this point jazz just means ‘not pop.’ Just play what you are feeling. That’s where the real music lies.”

Comments