Life, bro. Life.

Yeah, I cried. Like, real tears. I’m not talking about some pathetic, single anime teardrop. Not some bullshit-ass, Lil Wayne face-tattoo tears.

I’m talking about Selena death tears.

Brokeback Mountain tears.

Michael Jordan tears.

Nooooooo, not you, David Bowie! tears.

I’m talking real, manly-ass, Tiger Woods-apology tears.

And that was only by the one-mile marker.

We were in the outskirts of Boston, in Hopkinton, a small tree-lined suburb that didn’t look familiar at all because I’d never even been there before, yet everything was so nostalgic. Hey, look at that tree! Waaaaah! Ohhh that’s a beautiful house! Waaaaah! This pavement! It’s so … pavement-y! Waaaah!

I’d like to say I don’t know why I was crying as I ran toward mile two of the Boston Marathon, that it was some nebulous wave of emotion that crept upon me like a starving house cat, but I know exactly what happened: Life is fucking weird, man.

The City of Marky Mark

I grew up in Boston. It’s a city I love, but a place that formed my prepubescent psyche, so ingrained in the formation of my war-torn body and old, glitchy mind that it’s no longer just a city; it’s a catalogued collection of “firsts.” Boston is where I first learned to tie my shoes. Where I found out that teachers weren’t always kind. Where I ran away from a gang that was going to rob me. Where I gave my first awkward kiss to an awkward girl in an unmonitored corner of our elementary school. Where I learned the hard way that authority should always be questioned. Where I skipped school and rode the T to play video games in Downtown Crossing. Where I shoplifted my first piece of clothing from Filene’s Basement. Where I got into my first fistfight.

Here’s a story: Once, waiting for the train in Brookline, I saw Jordan Knight, one of the New Kids on the Block, waiting for a train going in the opposite direction. I don’t know why, but I flipped him off, and then he flipped me off back and did a little dance move—a dumb little flick of his hips, paired with a tip-toed Michael Jackson maneuver. He wore these leather pants with silver stars going up the leg, and I flipped him off again for dressing like an asshole. Then he got on the train and as it was pulling away he sat by the window and mouthed, “Fuck youuuuuuuuu,” all the while flipping me the bird. I picked up a rock, hurled it at the train and missed by at least 10 feet.

Boston is where I became a proper juvenile delinquent.

California Love

When I moved to California with my family in my early teens, I was well-versed in the ways of delinquent ninjutsu, a trait I honed until I left high school and moved back to Boston as an angsty teen, where I wandered around aimlessly, bumping Gang Starr in my headphones, hoping to get some sort of break in life. But I had no ambition. I worked in a bagel bakery and girls were repulsed by me. The only thing I liked were drugs. Lots of them. LSD, cocaine, meth, ecstasy, etc. And it wasn’t until I was fully immersed in a horrific drug culture that I started running. My friend Joe (who I met in kindergarten in a time-out box made for unruly children) invited me on a run. He was a student at Boston University on the track team, working at some fancy computer job. I was the opposite of that. My body was comprised of 70 percent whiskey, 10 percent cigarette smoke, 10 percent cocaine, 5 percent methamphetamine and another 5 percent black cloud of doom and uncertainty. I could barely run a block without having a heart attack. But that day I made it around the reservoir and I kept running. Maybe because running was my last tie to normal civilization. Maybe because it was my last connection to my best friend, Joe. Whatever it was, I started running more and more. I began to eat healthier. I stopped drinking. I quit doing drugs. Pretty soon, I was a runner. I entered short races, then longer races, and pretty soon I was running the 26.2 mile distance. Then the 50k distance. Then 50 miles. And now my doctor and my wife and family are telling me that I might be running too much. But I think part of me is afraid that if I stop running, even for a second, I will find an empty swimming pool, fill it to the coping with cocaine, dive in and never come back up for air.

The Humility of the Marathon

The night before the Boston Marathon, I didn’t sleep. I wasn’t nervous the weeks preceding the race. In fact, I was so busy at work that I hardly thought about the marathon at all. But the night before, sharing a bed with my wife and son who had come to cheer me on, I tossed and turned and carried that unbearable feeling in my stomach, like the night before a report card was to arrive in the mail. It’s not like I’d never run a marathon before. The Boston Marathon was my 11th marathon, which isn’t counting the five ultramarathons I’d run previously. So why was I so nervous? It didn’t make sense.

The morning of the race, I groggily slipped on my bright orange Fleet Feet Racing Team singlet and took the train to the start line. I could never understand when people say, “I am so humbled.” That phrase never made sense to me until, of course, I was sitting in a porta-potty with my head resting in my forearms, palms dripping with sweat as a line of people waited for me to empty my bowels. Pro tip: If you’re looking to experience true humility, hold the door open for a beautifully fit runner woman while she enters the porta-potty you just destroyed.

At the start line, I watched two men from Japan adjusting their gear. Written on their shirts in sloppy Sharpie was, “Double Boston Marathon. 52.2.” In the wee hours of the morning, they had run from the finish line to the start line and they were about to do the second leg of their journey. Then I saw a kid who had broken his leg and was “running” the marathon on crutches. There were soldiers running in heavy uniforms.

Of course I could run the race. What the hell was I thinking?

I found the other runners from my Fleet Feet Racing Team and wished them luck.

“Have fun,” I whispered to myself. And then we ran.

Past Hopkinton, down the hills of Ashland, into Framingham to Natick (about 10 miles into the race). The thing about the Boston Marathon is that the city shuts down. Everyone is outside cheering. During Sacramento’s California International Marathon, angry drivers honk at runners blocking their paths, but on Patriot’s Day in Boston, it’s one gigantic party. I’ve never been to a race with so many elated spectators. The halfway point is Wellesley College—a private women’s liberal arts college—where the students stand at the scream tunnel with sexually suggestive signs like, “KISS ME. I USE TONGUE.” I’d never been so excited during a run. Some runners even stopped to make out with the students. I looked at my watch, so entranced that I was running a six-minute pace.

As the miles passed, it got hot and I was running way too fast.

In Newton (mile 16) came the first big uphill, which is where the first runners stopped, their muscles tightening to a point of injury. The heat, the constant pounding, the overzealous running at the start of the race was starting to catch up. Runners clung to the guard rails, crying, clutching their calves, locked into submission. Luckily, I felt fine, even though I had run the American River 50-Mile Endurance run two weeks prior. Maybe it’s why the hills didn’t feel so brutal. Even as we climbed up the notorious “Heartbreak Hill” at mile 20, I felt OK, knowing that once I got to the top it was all downhill from there.

Finish Line

Of course, by the time I got to the top of Heartbreak Hill, I wanted to fucking die.

Running six more miles seemed impossible. But if there’s one solid thing drug culture taught me, it’s that you have to keep going until you can feel your soul leaving your body. So I did. I ran past Boston College, through Brookline, past the screaming Hasidic Jews. On Beacon Street, with only three miles left in the race, I couldn’t hear the crowd anymore, my calves twitching in Morse code yelling, “Stop running, you stupid moron.”

But I kept going, Boston’s illustrious silhouette glowing in the distance—the Citgo sign, a corporate monument of capitalism beckoning the runners like some false prophet.

And just like that, we were in the city, fallen runners scattered along the street, clinging to spectators, collapsing under the misdirection of their failing muscles. It looked like a war zone at mile 25 in Kenmore Square.

Turning onto Boylston Street I could hear the roar of the finish line, the memories flooding back: running from cops down Newbury Street; getting kicked out of the mall at Copley Place; being dragged to the Area D jail by undercover police …

Man, I wish I could explain, but the Boston Marathon is more than running 26 miles and 385 yards. It’s a commitment. To shedding old habits. To praising the body. To adoring your family. Cherishing friendships. To change. Improvement. To focus, loving every second you have left on this earth, speeding head-first into the unknown, muscles screaming in agony, tears soaking your clothes as you go, exhausted, exhilarated and beat down with a big, maniacal smile on your face.

**This piece first appeared in print on pages 22 – 23 of issue #239 (May 8 – 22, 2017)**

They’ve been called an emo band, which is weird. When I think of emo I think of a mopey teenager, clad in black, slouched in front of a 7-Eleven, writing dark poetry in a notebook while sucking on a clove cigarette and waiting for a homeless man to buy him beer. Actually, now that I think of it, that seems really fun.

But not as fun as Little Tents.

Little Tents is what I would call a pop punk band, but that’s the problem with labels: When I hear “pop punk,” I immediately think of Blink-182 and that’s exactly what I don’t want you to think of. Or, actually, think of Blink-182. I don’t give a shit. But Little Tents is pop punk in the way Jawbreaker was pop punk—melodically interesting, catchy, lyrically expressive, yet just hard enough to make your conservative uncle say, “What the fuck is this shit?”

Little Tents’ debut album Fun Colors (out now on Bomb Pop Records) is a short collection of seven quick songs that jump back and forth from melodic to chaotic, and it really couldn’t be any more delightful. And unexpected. Plus, there’s something enigmatic about the band. Perhaps it’s the upbeat tempo, which is pretty much the opposite of the dark, drone-y shoegaze that seems to have permeated underground music as of late. Or maybe there’s just something about Little Tents that isn’t quite right, an incongruous quality that I can’t quite pinpoint. For example, take these lyrics: “Inhale as the sky rains death. Through a haze, planes crack twilight/Smoke-filled teeth chatter with the chill of another night alive/The air will choke you. The water will kill you.”

That’s some darkly poetic shit, right? Some literature written by a deeply disturbed wordsmith? Maybe that’s why people call Little Tents “emo.” But the name of the song is “Shrimp Pants.”

“Shrimp Pants.”

It makes no sense.

Here’s another lyric: “Dawn gives birth to a bleeding child/The hope for a new day leaves us alone with a pile of tiny bones.”

Damn! That’s some evocative, Nobel laureate-type language, right?

“Khakis on the Beach.”

Yup.

So this begs the question: What does the song title “23N60” mean? Is it a super secret combination that unlocks a vault containing Little Tents’ vast fortunes? Is it the Bible Code? Or is it the name of an infectious disease?

To find the cut of Little Tents’ collective jib, I thought I would lure them with pizza (if there’s one thing a pop punk band loves it’s free pizza) so I could interrogate them. So, we—Lys Mayo (guitar), Audrey Motzer (guitar), Jordan Trucano (bass) and Adam Jennings (drums)— gather at Pete’s to hash it out.

They order a big ass pizza and some beer, and I order a douche-y vegan sandwich.

“So what does 23N60 mean?” I ask.

They laugh, while Mayo and Motzer explain that it’s the GPS coordinates of a weird logging road by the American River where they once got lost on a camping trip.

“Khakis on the Beach?”

Well, that song was named such because a guy wearing khakis walked by on the beach.

In short, there is no rhyme or reason as to why they name the songs the way they do. They just like naming songs weird stuff, so they do that.

I also wondered about who exactly sings the songs, because when you listen to the album, you hear a sweet voice and then a bunch of screaming, and it can be disorienting. For some reason, I figured Lys Mayo does most of the vocals, but it turns out Audrey Motzer sings a lot of them and Mayo does a lot of screaming. There’s also a dude (or a couple of dudes) who scream, too. Or maybe more. I don’t know. Even after they told me, it’s still confusing.

I think it’s confusing to them, too.

“She sings all the hits,” says Mayo, pointing at Motzer, who blushes.

It becomes wholly evident that the band does whatever feels right, which is often just an intuition and a willingness to practice until something cool-sounding comes out. In fact, it’s how their band became a band.

“[It] was me and Lys drinking in her backyard with acoustic guitars,” Motzer says. “We both didn’t know what we were doing at the time—and I still don’t.”

Their style of music comes from a wide swath of influences—local bands like Gentleman Surfer, Dead Dads (in which Mayo plays drums), Church and VVomen inform a portion of their musical landscape.

“Between all of us, we listen to a lot of different music,” Trucano says. “So we just threw it all together.” Jennings adds that they have all been friends since they were pre-teens, so they spend a lot of time together, sitting around, drinking beer and melding minds, the resulting songs a compilation of dueling ideas and differing tastes, a sort of auditory representation of their friendship.

“A lot of the decisions that we make for the structure of the songs is relatively arbitrary,” Jennings says. “We’ll kind of just pick it and do it that way every time.” They try to match their live songs to the way they’re recorded in the studio to maintain some sort of consistency.

This insight into the Little Tents process is fascinating, but, ultimately, super unhelpful when trying to trap them into a genre-specific categorical box. Nevertheless, we end up talking for a while as the band devours their cheese pizza, but none of what we cover—the lack of all-age venues, a sketchy house show where the hosts dosed unsuspecting guests with LSD, Sacramento’s inherent radness, Charles Albright getting shitfaced at a party—helps me understand Little Tents in the context of a genre or as a cohesive band. Everything they do seems to be on accident. Aside from their close friendship, there is no real narrative line that runs through the band’s history. They’re fascinating, of course, but only because of a random series of beautiful miscalculations. Or maybe not.

At the end of our conversation comes the most revealing part of the interview. There are two pieces of pizza left. Jennings eyes them both and slides them onto his plate. He reaches for the leftover ranch dressing and slathers it on one piece and puts the other piece of pizza on top. He then eats the slices like a sandwich. A pizza and ranch sandwich.

“How was your pizza sandwich?” I ask when he is finished.

“It was pretty tight,” replies Jennings, smiling a wide smile.

I’m here to tell you, friends: Little Tents are a band of genius punks.

Pick up a copy Little Tents’ debut album Fun Colors in digital form at Littletents.bandcamp.com or on CD at Bombpoprecords.com. Check them out on Facebook to look for upcoming show dates.

A Careful Tyranny

When Nails pulled up to their hotel in Helsinki, Finland, for last year’s appearance at the Tuska Open Air Metal Festival, they walked through the front doors, groggy and tired from the long international flight. That’s when vocalist/guitarist Todd Jones immediately spotted Bill Steer, the British guitarist for Carcass and Napalm Death, sitting right there in the lobby. He had to do a double-take. “We lost our minds,” Jones said in a moment of brief fanboy appreciation.

When the shock wore off, they went upstairs to rest before they had to start gearing up for their show. That night, Nails played a wicked set and after they finished, Jones went upstairs to sleep. He woke up a couple hours later to 20 text messages on his phone. “GET DOWN HERE,” his band members pleaded. “We’re hanging out with Phil Anselmo and the Illegals!” Anselmo (Pantera, Down) urged the band to wake up Jones and get him down there. “Where’s your singer?” Anselmo asked. “I want to meet my goofy cousin.”

The point is Anselmo, a goddamned metal legend, is into Nails, which is sort of a testament to the fact that the band—despite being heavy, dark, scary and alienating to most normal people—has something interesting to say outside of their local Southern California sphere. Let’s get it straight: Nails is not a great band because of a popular sound or crisp production or fancy guitar riffs—they’re great because every instance in every song is deliberate. For example, by starting “Depths” (from the album Unsilent Death), with a squeal and then a heavy chug of the guitars, the listener is placed in a desolate room, a dungeon, where the anticipation of what’s to come is frightening. And what actually arrives is scarier than anything we could have imagined. Jones’ vocals—powerful and desperate—are at once growling and high-pitched, and he conjures a dreary picture of the hateful world with dramatic screams worthy of a Tony award. The band can evoke the entire misery of the universe in one 14-minute album. Yes, that’s 10 songs in 14 minutes: Fuuuuuck.

Restrained Brutality

Jones, who is surprisingly soft spoken on the phone, uses his voice exactly how his band uses music: to pinpoint what needs to be said and to say it powerfully and economically, as not to waste time. “Restraint is a big part of our sound,” he says. “We have these ideas of what we want the band to sound like. We want Nails to be a very specific thing. If we make something that doesn’t fit into that, we’re just not going to use it. How often do we make a riff that we’re going to use? It’s very minimal. It takes us three years to make a record.”

Just think about that: Three years to make a record that will not last more than 20 minutes from start to finish. That’s a lot of thinking and planning and editing for such a short album. It’s beautiful how much thought goes into a Nails record, the end result being something like their latest album Abandon All Life, a tight collection of blistering hardcore and grindcore metal tracks that transport the listener to a very dark and frightening place. The band can be so scary that it’s hard to imagine the man I’m talking with on the phone goes to a day job and interacts with coworkers in a regular fashion. In fact, Jones, an IT guy during the day, doesn’t even tell his coworkers about his band at all. “I don’t talk to anyone about my band. They wouldn’t understand it. They would think I was some sort of freak or something,” he says. “Normal people don’t understand grindcore, death metal or hardcore.”

It’s true. Not many people get dark music, but those who do love Nails for their unique take on brutality, a sound that all comes down to Jones being a huge fan of music and his keen sense of not wanting to let anyone down, especially himself. “I don’t want to disappoint our fans,” he says. “Punk rock and hardcore could be simply bursts of energy. But I think my favorite bands, typically, have structure and restraint and it’s a very focused sound. I just want to be in a band that I like.”

“General Interest Poseur”

With Nails’ rising popularity comes a host of opportunities that were previously unheard of for bands who make heavy music—a brief partnership with the vehicle company Scion, for instance.

“They did a lot of good for us … when Scion was paying all these hardcore bands or metal bands to play shows for them. They treated people extremely well. Was it weird? Fuck yeah it was weird,” Jones says.

And, of course, when an underground band appears to have taken money from a sponsor, the message boards light up with purists claiming “sellout” and worse. After all, the enemy of heavy music is often thought to be corporations, or The Man, if you will. But Jones, a sensible man in his 30s, doesn’t really give a shit. The band’s strange partnerships and interesting opportunities (like a collaboration with Converse and Decibel Magazine) have allowed Nails to travel and/or expose their music to new people, which is all that really matters in the end. “I’m pretty much open to anything,” he says. “As long as it makes sense for us and we benefit and it doesn’t hurt us or our audience.”

Another strange aspect to the band’s rising popularity is reviews from music media outlets, such Pitchfork, which is often thought of as the hipster Holy Grail for pretentious indie reviews, a publication that runs off equal parts snark and hipster fumes to make (and mostly break) music careers. A hardcore band like Nails doesn’t exactly expect to get a rave review from such a publication.

“I was not expecting, but I am very grateful for it. More importantly, [writer Brandon Stosuy] understood our record. It feels good to be understood,” Jones says.

However, interestingly enough, not all good reviews are equal. For example, Anthony Fantano from The Needle Drop—the self-described “Internet’s busiest music nerd”—enjoyed both Nails albums, but Jones is not nearly as enthusiastic about his review, simply for the fact that Fantano obviously doesn’t understand the band at all.

“He’s the kind of person that listens to anything and can kind of find the good in it. At the end of the day I don’t think we’re a band that those people can really jive with. I think our band is too extreme,” he says. “So if someone’s going to hit me up and say ‘What do you think of Anthony Fantano’s review?’ I think it’s cool, but I think he’s a general interest poseur.”

California Torture

While Jones won’t reveal the name of Nails’ new album, he says it’s just about done and, more importantly, that it’s going to be brutal as fuck.

“If you took our first album, Unsilent Death, and held it up against Abandon All Life, it’s basically a progression in the same direction—a little bit more metal, a little bit more technical, but also in some ways it’s a lot more Neanderthal. All I can say is it’s through-and-through a Nails record. We are taking the same caution and restraint and carefulness with writing this record that we did with Unsilent Death and Abandon All Life,” Jones says. “If you’re willing to go a bit more extreme with us, then this one might be your favorite.”

To be honest, it’s sort of horrifying to imagine an album more extreme than Unsilent Death and Abandon All Life. But for fans of heavy music, and for people who know exactly what Nails is capable of, the idea of Nails magnified is thrilling. We can only hope that the band will unleash a few of the new songs when they stop in Sacramento, where they last played several years ago to a nearly empty room.

“There wasn’t very many people and nobody really knew who we were,” Jones says about the house show they played back in 2010.

But it’s 2015. The world still sucks. We’re all broke. Cops are killing everyone. California is dry and everything is lighting on fire. Which is a perfect atmosphere for Nails’ disparate melancholy and unadulterated rage. When they come, Sacramento will never be the same. It will be worse. And you’ll probably want to be there for the mayhem.

See Nails live at Midtown Barfly in Sacramento on Aug. 22, 2015. Pins of Light and Human Nature will also perform. This 18-and-over show has a $12 admission and gets underway at 6 p.m. Midtown Barfly is located at 1119 21st Street, Sacramento. Get tickets in advance at Shufflesix.queueapp.com

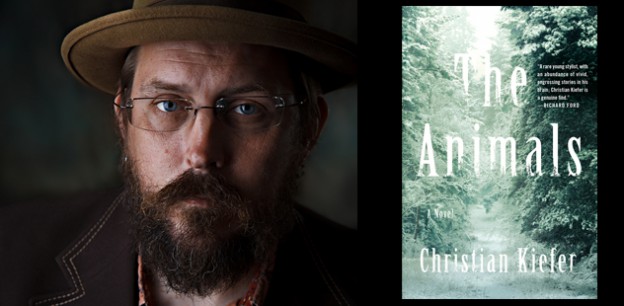

Even As Christian Kiefer Unveils His Latest Book, The Animals, He’s Already Hard at Work on His Next

I didn’t think Newcastle was a real place. I figured Christian Kiefer didn’t want me to go to his house, so he made up some fictional land as a way to tell me to fuck off. But not only is Newcastle a real place, it’s really close to Sacramento.

On the way there, as the scenery turned from strip malls to pristine megachurches and finally to layers of thick, healthy trees, it sort of made sense that Kiefer would want to get as far away from the city as possible. Not that Sacramento is some major metropolis, but he’s a busy man and probably doesn’t need any more clutter to infect a mind that’s always trying to think.

And when I say busy, he’s busy. He’s a father of at least 400 children (OK, maybe like 5), a husband, a musician, a professor at American River College, a writer and, for some reason that I don’t fully understand, he has a bunch of sheep. Plus, he built a back patio on his house. I don’t know what else he does, but I didn’t want to ask. I felt bad enough about my life as it was.

But, of all those activities, Kiefer probably loves writing the most. (Sorry, kids.)

Even when he’s teaching, hanging out with his understanding wife or tending to his children and sheep, he’s constructing new narratives that start as little seedlings in his brain and bloom into real books that are adored by masters like Denis Johnson and T.C. Boyle.

His 2012 debut The Infinite Tides, a novel about a perpetually bummed out astronaut caught in a suburban labyrinth of grief crafted by his own bad decisions, garnered excellent praise, including a Publisher’s Weekly review that called the book “an astute, impressive and ambitious debut.”

His second book, The Animals (out March 23), is about a man who is trying to correct his troubled past, which comes speeding back, threatening to derail everything he’s been so careful trying to rebuild. The book (which Kirkus Reviews called “Eloquent and shattering”) is thrilling, especially compared to Tides’ occasionally plodding introspection, yet it retains Kiefer’s curiosity with language and with the world around him with poetic writing that entrances the reader completely. The Animals is dark, but humorous exactly where it needs to be. One of my favorite scenes is a flashback where the villainous Rick is trying to get his buddy Nat laid in a bar:

“She might have been forty, although she wore so much makeup it was difficult to tell, eyes wiped with turquoise as thick as paint and hair like a bundle of blond wires. She licked her lips. He had seen animals in nature documentaries perform similar actions while feeding on carcasses in the plains of Africa.”

With The Animals still fresh in the world, Kiefer works on his third book, Kingdom of Wolves, which seems to be pushing back a little, giving the author a bit of trouble. Still, he invited me over to his countryside home for a little chat in his writing studio, a big shed full of books and instruments that sits behind his house, next to the trampoline where his little blonde children bounce and scream in exhilaration.

When I exit the freeway and follow the signs to Newcastle, I know I’m close to Kiefer’s house because:

a) It looks like the end of civilization

b) I have to drive down a dirt road

c) I have to stop my car to wait for some asshole turkey that’s waddling in front of my car like it owns the place.

Why do you live all the way out here?

I’ve always lived out here. I grew up in Auburn.

You like it out here because it’s away from things?

I’ve never lived in Sacramento. Sacramento is just the town that’s in the way when I’m going to San Francisco. I’m not a city kid. It’s too much stimulus or the pace is wrong for me or something. When I visit town, I have fun, but I’m ready to go home.

To your nine children?

Yes, to my 50 kids.

My mom swears you’re a Mormon.

I’m just overpopulating the earth. I can’t imagine raising the kids in a city. I remember walking around Chicago or Boston or something and realizing that all the schools were totally inside, even the playgrounds. That’s weird. I just need to be out with the birds and the trees. And the monkeys.

I don’t understand how you do all this. You write. You teach full-time. You do music. You build shit. You have a family.

My wife and I have a very clear division of labor. She does all the in-house stuff. I do all the out-of-house stuff. So I do all the shopping, oil changes, anything that involves driving anywhere, I do that. And she handles all the bills and the food preparation and that works out pretty well. I run the errands on the way home, and when I’m home I have no homework. I’ve also gotten pretty good at not bringing my ARC work home.

You got amazing blurbs for The Animals. Whenever I read that Richard Ford one that calls you a “rare young stylist” I picture you as a flamboyant hairdresser.

I wrote him and said, “You know I’m 43, right?” and he wrote back and said, “Yeah, I’m 70.” That these guys—Richard Ford, Denis Johnson, T.C. Boyle, Pam Houston—I can’t believe any of them even talk to me at all. What’s in it for them? Nothing. But I have a relationship with all those guys that they’re willing to suffer my communications and why I’m lucky enough to be treated like that I have no idea.

That’s great.

I’m a mailer out of fan mail. I do that all the time. I’m reading at Book Passage next month so I wrote a letter to George Lucas and just said, “If you wanna come, man …”

What? Do you just send the letter to their agents or whatever?

Or sometimes you get an address. A lady that interviewed me about The Animals for The Nervous Breakdown…was asking me about Van Halen in the book. She goes, “By the way, my boyfriend is David Lee Roth’s personal assistant. If you want to get a book to him, I’ll give you his address.”

So right now David Lee Roth is reading The Animals?

He has a copy of The Animals. Who knows if he’s reading it. I know he’s a reader, but who knows. I hope my phone rings at any moment—“I gotta go, it’s Diamond Dave!”

Do you think of being a local journalist as a shitty time in your life?

I think of it as something I did wrong.

Why do you say that?

I was writing mostly about music and I am a musician, and I wrote about music as if Sacramento could handle it. I wrote about music in a very critical way. I was very hard. Not harsh, but hard to please. People like Jerry Perry would get on my case a bit about shooting fish in a barrel. And at the time I didn’t give it much credence but now I wonder if that argument isn’t right. Maybe I should have written about architecture or something else.

What about reviews for The Animals? Any bad reviews?

The thing about a bad review is even if they didn’t like the book, it takes eight hours to read a book, so even if they didn’t like it that means they spent a whole day with you. I still have to give them credit for doing that work. I’m really curious to see what The Animals does in the world because it’s so different for me. When Tides was hauling ass it was going like 5 miles per hour. When this is hauling ass, it’s actually hauling ass. So I’m curious what the bad reviews are going to be.

Can you anticipate them?

Maybe that it’s obvious or something. The setup is pretty obvious—the bad guy is coming back and at some point they are going to start fighting. But I wanted it to have a sense of real narrative clarity because Tides doesn’t. And Kingdom of Wolves is just a total clusterfuck of plot.

Is that how you’re going to market Kingdom of Wolves, as a giant clusterfuck?

I’m going to have Morgan Freeman say that. Every time you open the book, he’ll go, “A clusterfuck of plot.”

Weird, man. You’re a weird dude.

Yes, I am. Yes, I am.

Stop by Time Tested Books in Sacramento (1114 21st Street) as Christian Kiefer reads from The Animals on Thursday, April 2, 2015 at 7 p.m. This is a free event.

I love Lee Spielman’s tweets. Sometimes you can tell he’s been smoking weed: “Antwon just showed me a photo of @JLo and said ‘Look @MelissaJoanHart got ass.’” Other times, you can tell he’s high out of his goddamn mind: “You ever stop and admire how nice someone’s front yard is?” And, on occasion, his tweets are downright frightening: “Talking to the Sacramento newspaper later today about playing our first show there in about 7 years. Might Marshawn Lynch the interview.” Ah, Lord. Do you know what is worse than an awkward interview? Nothing. So for the next day I was truly scared about talking with Spielman, the singer whose band Trash Talk I consider one of my favorites.

Trash Talk has been playing hardcore music for the past 10 years and the band has seen a dizzying amount of success, especially for such an aggressive, not-pop-friendly band. They’ve played huge festivals, gotten to work with incredible producers—like Steve Albini (on the Trash Talk album) and Alchemist (on No Peace)—and they even signed to the Odd Future label, which still confuses hardcore and punk purists to this day.

The band, known for their chaotic live shows where the crowd tends to break limbs and destroy venues, is 100 percent chaotic energy. So, needless to say, the prospect of talking with Spielman was exciting, and I had a lot of questions for the Sacramento native. I wanted to know what he thinks about his old hometown and why he left; I wanted to ask him about his collaboration with Odd Future; I was dying to hear him discuss his band’s wild reputation and some of the trouble he’s gotten into with Trash Talk; and I was also wondering why his publicist said he was working construction.

So, I guess the question is: Did Lee Spielman Marshawn Lynch this interview? Well, that’s up to you to decide.

I was so stoked to see you still have a 916 number.

Yeah, I’ve had the same number since I’ve ever had a phone.

The publicist said you were doing construction.

No, I’m building something for us.

What are you building?

Just a bunch of shit for our tour. A bunch of crazy shit. I can’t really talk about it. You’ll see eventually.

Do you work on a lot of other stuff that’s not music?

Yeah, we’re working on a lot of shit. That’s why I’ve been building all fucking day. Working on a lot more stuff that’s outside the box. The last couple months we’ve been having a lot of fun doing creative stuff, from, like, art and ‘zines to collaborating with other artists and brands that we like and not keeping it so cookie cutter on our side.

Oh, OK. Man, I love No Peace. It’s so good.

I appreciate that, man. We were trying to do something different from the demos to what we have now. I don’t even know what the next stuff is going to sound like, but it’s just kind of boring to make the same music over and over. We all know by this point we know how to make short, fast, aggressive punk songs. It’s kind of fun to test ourselves, and we try to do that every time.

When you think back to the beginning of Trash Talk is it odd to think that your little hardcore band ended up being successful and you’re getting to tour and travel and things like that?

Yeah, it is weird. But, then again, it’s something I’ve always loved and have been involved in forever. So it’s weird, but I don’t know what else I would want to do. I’ve been involved with this stuff since I was a little kid, so it almost makes sense. And it’s kind of rad that it turned out the way it did. But I think [our success is] because ever since we started we’ve been 100-percent all the way.

What do you think you would be doing if you weren’t in Trash Talk?

I have no idea. I’d probably would have went to college and shit like that.

Is it weird that we still kind of claim you as a Sacramento band?

I did a lot of things there as a kid. We started playing there when I was a little kid. I booked shows there for the better part of high school years. It was almost like I could say that I learned how to be in a band and how to tour through booking shows in Sacramento.

Was that at Westcoast Worldwide?

Yeah. [Mike Hood] would leave for tour and me and my friend Jason T. would legitimately go to every single show there. We didn’t care what kind of band it was, whether it was a thrash band, a punk band, whatever. I don’t even think they knew my name until the first year. We went so many times and…we kind of took over for a little while. That taught me how to treat bands on tour—how to pay bands, how to book shows, how to promote shows. I kind of owe that whole area of us starting [to that period of time] because I booked all our first tours and it was like, “Hey, remember that time I booked you a show in Sacramento? Can you book me a show in New Jersey?” It was just kind of a tradeoff and punk and hardcore is cool for that. I met all my best friends like that.

Anthony Anzaldo from Ceremony was talking about Westcoast Worldwide and he remembers it being a huge pile of shit.

Yeah, it was a shithole. But it was our shithole, so it was OK.

Do you ever miss Sacramento?

Yeah, my family still lives there. Some of my best friends still live there. I’ve just been going so hard doing other shit. I don’t know, the day I turned 18 I got in our bass player’s car and drove straight to Seattle, and then I haven’t moved back home since then. But it’s been fun because I’ve lived in London, Seattle, Philadelphia, San Francisco, Richmond, Virginia. I feel like every kid should get out and see what’s up. Sacramento is a beautiful place and I’d be psyched to have a house there one day or some shit. I’m too young to be stuck there right now.

Do you think it was important for your band to get out of this place and just go?

I think we got to the point where it was like we were getting asked to play a lot of shows in Southern California and stuff and it was like, “Fuck it, let’s just go to Southern California. We drive there every weekend, anyway.” We all kind of moved apart. Our bass player was living in Bakersfield, our drummer in Los Angeles, our guitar player in Seattle, so one of the main reasons of me moving out was so we could all move to one place and operate as a unit. That helped us get a lot of shit done.

What has Odd Future helped you do?

There’s just other opportunities. It’s more like a whole new set of eyes and ears to work with on the creative side. And just kids in general. I don’t feel that punk and hardcore should be stuck to punk and hardcore kids. [Music should be] projected to someone that can make their own opinion to whether or not they like it, but a lot of time people don’t get the chance. Some kid at an Odd Future show may never have heard of anything like this, but the second he sees it he’ll know it’s his favorite shit. So I think it’s really important to do shit like that in general. Like, we’re coming through Sacramento with Ratking. We’re down to play with Wavves. Or a DJ. Or whatever. It doesn’t matter.

I never heard Ratking until I looked at your flyer and YouTube’d them. They’re really good.

That’s what it’s all about. Shit like that. And then vice-versa. There’s probably a kid in Sacramento who’s never heard of us and going to see Ratking and typed [Trash Talk] in and is like, “Damn, this is tight.”

Skateboarding has always had this connection between punk rock and hip-hop.

I’ve always said that forever. Like, Ratking, we’re going on tour with them. There may rap and stuff and we play a different genre or style of music, but at the same time we’re all the same kids. We got into music for a reason and we’re traveling with our friends, seeing the world, having fun—skating, tagging—doing whatever we want. At the end of the day, regardless of the genre, we’re kind of the same kids.

Since you guys are touring so much, do you ever just get tired out? Like you don’t even want to go on stage?

For sure. Sometimes I’m like, “This fucking sucks. I can’t do this.” But then maybe like 10 seconds before the first note it’s like, “Alright, this is OK.” Then five minutes into the set it’s like, “This is fucking sick.” Halfway through it’s like you forgot how you’re feeling. But this next tour is like 30 days. It’s definitely going to take its toll.

Have you ever played Harlow’s before?

No, I’ve never been there. Is it on J Street or some shit?

Yeah, it has a weird ‘80s lounge vibe. And VIP booths.

That’s tight. We haven’t played Sacramento in hella long. I’m curious to see what’s going to happen.

Do you guys get in a lot of trouble at your shows?

Yeah, a lot. It’s a blessing and a curse. It’s one of those things, people book us to play and they’re like, “Oh, I want this crazy show!” and they get it and they’re super bummed. The crowd’s not bummed. It’s usually the owners or some shit. But it’s not like we ever go out of our way to intentionally break anything. It’s usually not even us. It’s usually the crowd doing too much. We’ve been in trouble a shitload of times. We’ve had riots. We’ve had police shut down our shows. It’s kind of weird now. Every time we pull up, they know we’re pulling up and they have a list of rules of shit we can’t do before we walk in the building.

Is there one rule that people always have for you guys?

Don’t climb on shit.

Well, good, man. I’m glad you didn’t Marshawn Lynch me.

I thought about it.

Who knows what will happen when Trash Talk plays Harlow’s. That’s why you have to be there to find out. The show is March 16 and also features Ratking and Lee Bannon. Tickets for the all-ages show are $15 in advance and can be purchased at Harlows.com.

Though It May Seem the World of Hardcore is Getting Nicer, Hoods is Just as Scary as Ever

I remember being at a Hoods show back in the ’90s, watching some unfortunate kid getting the shit kicked out of him. For some reason, I stood against the wall, laughing. The poor guy was really getting it bad—Doc Martens to the face and everything—and there I was, giggling like an idiot. That is, until a fist flew out of nowhere into my nose, snapping it clean in two. It must have been some sort of punk rock, karmic retribution. There was blood. Lots of blood. My white T-shirt turned crimson. Nobody came to my rescue. The show went on. I woke up the next morning, proudly sporting one of the most prolific black eyes I’d ever worn. I couldn’t breathe through my nose that had swelled up overnight three times its original size.

Those were the days. Hardcore isn’t like that anymore. Sure, there are some scary bands, but the live shows don’t seem to have as much rage. Maybe people aren’t as angry as they were 20 years ago. Back then, all we had was Sabrina, the Teenage Witch and dial-up Internet connections. We were pissed. The point is that Hoods is still a scary band, maybe even scarier now that singer/guitarist Mikey Hood started drinking and smoking a bunch of weed. In fact, the new album, Gato Negro (Spanish, I think, for “We’re old, but we’re still going to fuck you up”), is just as brutal as their debut Once Again and even heavier than the celebrated Victory Records release Pit Beast. Gato Negro teeters on the edge of metal and hardcore, but ends up somewhere along the lines of street punk. Songs like “Middle Class Wash Out” have just enough melody mixed with brutality to show listeners that these are musicians who know exactly how to make fucked up music that jumps out of nowhere, punches you in the face and breaks your nose when you least expect it. It’s the best kind of nostalgia.

I got a chance to talk with Hoods vocalist/guitarist Mikey Hood about his old venue Westcoast Worldwide, cutting hair, fighting, tours, and, of course, weed. Lots of weed.

Hey.

Sorry it took so long to call you back, but we got home and got stoned and I was like, “Shit, I know I’m supposed to do something very important.”

Ah, the fucking weed. So do you miss Westcoast Worldwide?

Yeah, of course. We’re looking at opening a new one probably next year some time. It’s going to follow suit with rehearsal studios and stuff like that. I definitely want to do a live venue, but I want to do it with four or five people as a collective. Doing it all alone drains you. It’s like having an extra job on top of what you already have to do in life to make it.

What have you been up to the last few years?

We’ve been touring still. It’s just we haven’t been touring in the States. To play locally, people in your hometown don’t appreciate you as much as they do in other spots because they have the opportunity to see you. So we stopped playing all the time and then it started creating normal draws again. We did Europe for almost a month and we flew to [Philadelphia] and did Tsunami Fest and that was pretty cool. We played with Cro-Mags, Sick of it All, Obituary, All Out War.

Was it pretty crazy?

I missed it. I had an allergy attack, but everybody else loved it. I could hear it from the van. I made our set and then nearly collapsed.

Are kids different now at shows?

Yeah. Somewhat. The older dudes are still kind of nutters, but the younger kids … it’s more like a popular thing to be into hardcore now, as opposed to something you have a passion for. It’s cool to act tough when you don’t have to even be tough. You can just be a nice dude.

I used to be scared going to hardcore shows.

Now it’s kind of like a bunch of clowns doing karate moves. It doesn’t seem like they really feel it anymore. It’s kind of good it’s not as violent, but at the same time it took a lot of the realness out of it, I guess.

How was Europe?

Really good. We did 22 shows pretty much in 22 days. We played Finland, Germany, Belgium, Holland, Poland, Austria and we did a bunch of shows in France. The shows were really good, but the country’s a little bit suspect.

Really?

They’re fucking assholes. Fuck it.

Why do you say that?

I don’t know, man. The kids at the show are cool, but when you have to deal with somebody in public they’re fucking assholes. As you go southwest, like to Bordeaux, the people are really cool, but some of the people in Paris and Marseille, they’re just really arrogant, man. If you ask them something in French, they’ll just look at you like you’re fucking stupid. It’s like, “I’m going to slap your fucking face with a baguette. You’re lucky I’m an American because if we didn’t help you in World War II, you’d be speaking German.”

So have you chilled out on your fighting ways?

Man, I didn’t know I really did get in a lot of fights.

Really?!

I don’t know. I guess … I don’t know. Did I?

Maybe it’s just a Sacramento legend. Those legends don’t even have to be true.

Dude. The thing is I haven’t been in a fight since—shit, no, actually can’t say that, but I haven’t tried to get in any fights in years. I don’t think we really ever started fights. I guess I was a little aggressive, but when I needed to be.

When did you start smoking weed?

Check it out, when I was 35, I was going to go back to college and try to finish up my A.A. degree. My friend’s like, “You gotta get this Adderall shit.” And I tried that shit and took it for three days. That shit kept me up for a fucking week. I got a lot done. I cleaned the house at least five or six times a day. I changed the oil in my car and sent all my old postage out. So it wasn’t a total loss I guess.

Then you started smoking weed?

Oh, yeah. I smoked weed for about five years. It’s funny, because everybody who knows is like, “You fucking hate hippies.” But actually I’m kind of a hippie. The only difference is I take showers and go to work and shit.

Do you ever smoke weed and trip out on your straight edge tattoos?

Oh, dude, no way, man. Straight edge shit’s cool, man. That shit kept me out of jail. Actually, if I was smoking weed, I probably wouldn’t have gotten in as much trouble, but it wouldn’t have been as fun. Yeah, so fuck it.

How’s your barber shop going?

That shit is fun as fuck. I like going to work. It’s a good job, too. You don’t get bored, man. You get like at least five to 10 dudes a day coming through all with different stories. Your day changes drastically from haircut-to-haircut. Most people hate their jobs. I actually like mine.

Let’s talk about your new album.

You already got a copy?

Yeah.

I honestly haven’t even heard the final product yet. I’m hella excited.

Well, it’s good.

I like that song “Gato Negro.” It’s the one we’re going to do a video for.

It’s got a cool melody.

It’s more like street punk-ish.

You know when you hear a new hardcore record and you’re worried that it’s going to be all soft and boring?

Oh yeah, this one had a while to bake in the oven. I’ve been writing some of these songs since Pit Beast came out. I’ve had about six of these songs for two years, at least, and then I kind of just rewrote them. I wrote a couple songs on the spot. I wrote the “Gato Negro” song on a “verse/chorus/verse/chorus/done” and we did it the next day in the studio and it’s like my favorite song off it. Sorry, I’m stoned. I’m getting off track. I think people are going to like it. And if they don’t I don’t care because my cats will like it.

What’s your most fucked up show story?

The tour was called Street Brutality Tour. It was Hoods, Shattered Realm and Donnybrook. It’s kind of like if you picked out the more thuggish kids in hardcore and put them on tour, this would be it. It was L.A., Sacramento, New Jersey, New York—so we covered pretty much every region. It was fucked up. There was a lot of tension that tour. To say the least, some kid got killed when we played at Skrappy’s in Tucson, Arizona. That was the same period when Dimebag Darrell had gotten shot on stage. I lost some friends that year. That made me not want to play music any more because when motherfuckers are coming to shows with AK-47s, that tough guy shit’s out the window. That’s when it gets really real. I don’t know about you, but I got shit to lose and I’m not trying to fuck around with being on some crew shit. It was stupid then, and it’s even stupider now.

Tell me about your walks that you take.

You’ve seen The Evil Dead, right?

Yeah.

You know when he’s walking out of the forest at the end and the thing comes and kills him?

Yeah.

The death walk is like that, but in the motherfucking pitch darkness. We get hella stoned. We get zombie, Cheech and Chong stoned and then we go on the death walks. You got to walk through. It’s maybe a third of a mile. It’s like a trail. There’s raspberry bushes and all this overgrowth shit. You can hear noises. There are some transients that live in there. So we call it the death walk. It’s pretty cool.

That sounds horrible.

Oh no. It’s healthy. You burn calories when you’re scared.

Hoods’ Gato Negro will be released Nov. 25, 2014, via Artery Recordings. Five days later (Nov. 30, 2014), you can celebrate its release at Blue Lamp. The show gets underway at 7 p.m. Check out Bluelampsacramento.com for more info. Mikey’s shop, True Blue Barber and Shave Parlour, is located at 1422 28th Street in Sacramento. Stop by and say hello!

Mahtie Bush – Child’s Play

Sacramento MC Mahtie Bush’s fourth studio album Child’s Play is a solid, slightly inconsistent collection that’s risky, poetic and, at times, mildly frustrating.

Bush is something of a Sacramento legend. And rightfully so. Renowned for his incredible work ethic and dedication to hip-hop culture, Bush has hustled his ass off, paving the way for a whole new generation of Northern California MCs. So, of course, from this seasoned MC, we expect many highlights and real gems (both of which this album provides), but on top of that we expect an anthem, a track that blows every other local song out of the water. In 2010, Bush gave us the boisterous “Backpackramento.” On Child’s Play, he gives us “Let Go,” an example of Bush at his finest, where a simple beat, hand claps and multi-layered punch lines are all that’s needed to create razor-sharp battle raps that go for the jugular with lines like, “Piss me off and get pissed on and flipped on and flipped off/Tell you and your GPS system to get lost, dog/I can’t lose/Shit on a Shih Tzu/Each line I write is trying to offend you.”

When Mahtie Bush is hyped up, he’s utterly unstoppable.

But Bush isn’t just a battle rapper. He’s also a conceptual thinker with the ability to construct songs that involve the listener on a more playful level, as he does on the track “On the House,” which allows him to stretch out, offering a quick, fun, lyrical glimpse into the distinctive Sacramento lifestyle over a quirky ‘70s-style beat. Almost midway through Child’s Play, the listener is treated to a wide array of styles from an MC who understands the diminished attention span of the average modern listener. But instead of dumbing down the verses, Bush simply varies the content, from battle raps to rugged flows to abstract works of art like “Blood Runs Cold,” where he slips into the mind of a poet, spitting cerebral bars like “Venom over chipped ice/This is what life tastes like/Snake bites from fake types/Serpents never play nice” that stab at the listener’s senses until they’re raw, as he singlehandedly embodies the unwieldy spirit of the entire Wu-Tang Clan in one track.

But Child’s Play isn’t without its flaws. The album lags in spots where Bush falls out of the pocket during some of his more expository moments, often letting his message overshadow sonic impact when he tries awkwardly to fit syllables into bars where they don’t belong (at his worst, Bush sounds like he might be having a stroke). For example, on “I Ain’t Believing That,” Bush’s rhymes are so oddly placed that they mangle the life out of the immaculately utilized Suzanne Vega and Fugees samples that the exquisite production has to offer.

Also, and this might be nitpicking, but when Bush tries too hard to get a point across, he dangerously flirts with sentimentality. For instance, a song about his son’s birth is fine, but, as is true with any writing, avoiding sappiness is the key to communication. So lyrics like “These Braxton Hicks is not what I had in mind/I just want you healthy/I know things will be fine/Eating healthy so your mom’s blood pressure is fine” just aren’t cutting it. The song also goes in and out of second person, so what could have been an interesting letter to his newborn son turns into a lesson on sentimentality and inconsistency.

Despite a couple middle-of-the-road and slightly forgettable rap tracks like “Here We Go Again” and “Pile of Bones,” the 11-track album offers way more positives than negatives. Bush manages to take risks, spill his guts and capture the plight of a gracefully aging MC who gently balances love of his city and the poetry that it inspires with his newfound role as a father and husband. Bush proves elegantly once again with Child’s Play that he’s a serious, versatile MC who is all grown up with tons more to say—and he’s not putting down the microphone any time soon.

After a lifetime in Sacramento, Matt Sertich is taking his solo act to L.A.

A healthy crowd gathers in Midtown for an early show in celebration of Matt Sertich’s first solo record, The Only Way Out is Through, a collection of stripped down, powerful pop songs that speak to love, pain, loss and all the other weird shit that creates the human experience. The vibe is mellow in Harlow’s, a room that can transform from an intimate singer-songwriter cave into a Latin dance extravaganza in the blink of an eye. The bartender is nowhere to be seen. Security guards stand leisurely, making jokes. Toward the back of the club, a table full of dedicated fans who have been following Sertich for decades, from his time in the pop-punk outfit Pocket Change to his 10-year stint in The Generals (with drummer/keyboardist/programmer Kirk Janowiak) to his present day solo career, let out a collective scream when the 37-year-old musician finally sits at the piano.

Sertich wastes no time. He breaks into “I Won’t Let You Down”—a strong, earnest ballad with an atmospheric background—and the room falls silent. His voice is loud and confident, with a thin string of pain that runs deep through his soaring melodies. Sertich is an interesting musician in that the songs he crafts are not exactly what count as popular today. In an era when singers either emulate rustic Americana or stare at the ground feigning disinterest in the world, Sertich chooses to face emotion head-on and write songs that celebrate life’s loftiest themes—pop-y ballads about love and hope. And what he creates comes from an almost childlike approach to music. “As a kid your dream is to write stuff like U2 or Whitney Houston … or what makes you feel so good inside,” he explains. “And as you get older you start getting into scenes and you start reverting backwards, kind of.”

After some soul searching, Sertich realized that he doesn’t have to cater to a scene or a trend. He’s going to make the kind of music that he wanted to make as a kid. And he does it well up there on that stage, singing like he’s trying to win back the girl of his dreams. The crowd, of course, is transfixed.

But Sertich hasn’t always had such good fortune with his music. In fact, much of what he’s faced is enough to make a weaker-willed musician smash his guitar, get a state job, crank out a litter of children and exit without so much as a whimper into the eternal bucket of KFC in the sky. But some of the stories he tells of his frustrating misfortunes are actually pretty funny. You know, once the heartbreak settles in.

For instance, there was a run-in with a Sacramento radio guy a few years back after he wrote “Keep the City Alive,” an ode to the the Sacramento Kings. Naturally, Sertich was excited about debuting his song on-air, but the radio guy played the song and immediately said it was horrible, that it sounded like Say Anything or Peter Gabriel. For Sertich, it was a confusing put down. After all, in his mind, a Peter Gabriel comparison isn’t quite the end of the world. But, still, it was a slight. And it was meant to be harsh.

Or there was one time he went to Los Angeles to be on the popular Heidi and Frank Show (95.5 KLOS). He was super excited about the appearance. That is until he arrived at the studio and found out he was booked for a “love it or hate it” episode, where the hosts would play your song and critique it (along with random callers) live on the air. They played The Generals’ “Just Because,” a fast-paced pop ballad about hope in the midst of darkness. The calls came in. One-after-another. Heidi hated it. Mike said it sounded like a Cure cover band. The song played through and Sertich sat through scathing, seemingly endless criticism. “It was so painful,” he says. “They were just ripping it.”

Anyway, Sertich somehow ended up garnering six votes, enough to sit for the rest of the show. Still, he was discouraged. But that situation—the uncomfortable, nearly unbearable awkwardness—made him stronger, more determined than ever to succeed.

“But I never want to play ‘Just Because’ again,” he admits. “I hate that song.”

Finally, after a weird run-in with The Jim Rose Circus Sideshow, where he was promised thousands of dollars to go on tour, which turned out to be a scam, The Generals decided to amicably call it quits, and Sertich decided to get his solo career off the ground. “I think with Kirk that was the last straw,” Sertich says. “It just depleted him.”

So, as The Generals winded down, Sertich worked as hard as he could on music in between his full-time job waiting tables at Tower Café. He practiced literally every day for a year—no matter how tired he was or how uninspired he felt—and came up with six tracks of piano-based ballads that became The Only Way Out is Through that he performs by himself with a synthesizer and drum machine. In the spirit of The Generals, Sertich’s solo songs are powerful, ’80s-tinged melodies that stand out, especially in 2014’s musical landscape of throwaway pop songs that rely more on tricky production than emotion.

“I grew up loving ballad singers,” Sertich says. “Like cheesy love songs that people make fun of.”

But oftentimes, people make fun of things that are memorable. And popular. Sertich’s obsession for ballads and his ear for powerful, larger-than-life arrangement results in a cinematic vibe, songs you might hear at the end of a movie where the protagonist screams triumphantly in the rain, even though all his friends are dead.

Since Sacramento might not be the best place for an artist like Sertich, he’s packing up his belongings, leaving Sacramento, the only home he’s known for the past 37 years, and taking his movie-ready songs down to Los Angeles, just to see what happens.

When I ask what he’s going to do down there, Sertich points to his CD. “There’s my business card,” he says. “There’s a lot of stuff going on out there. Just to reach out to as many avenues as I can when I’m out there, whether it’s playing as much as possible, networking, going to see a show.”

It’s not going to be an easy road. Sertich knows that. He’ll probably rent a room in Silver Lake, work as a parking valet and do his best to get his music into the hands of the right people. A scary prospect, but for someone who obsesses over melodies and arrangements, it makes perfect sense.

“I’m going to be full of fear because I’ve lived here all my life. There’s a lot of ups and downs. I get it, but it’s just going out there focused,” he says. “I’m not going out there because I’m trying to run away from anything, I’m going out there because I want to make it happen. It’s what I want to do. I don’t have a choice in the matter anymore.”

At Harlow’s, Sertich sits at the piano in the middle of the dark stage, red lights casting an eerie glow against his pale skin. He plays the song “In the End,” written as a letter from his father who passed away in 2005. It begins, “Son, I’m leaving now/ My time has come/ to say goodbye/ Son, I hope you know/ I’ve done the best/ that I could. I never meant to do you wrong/ Never meant to leave you there/ Leave you all alone.”

When Sertich sings, it’s not just the voice. It’s every atom in his body. In his muscles. His skin. Emotions stir in an aura that surrounds him, both joyful and dark. “And I only meant to be your friend,” he sings. “Hope you knew me better in … better in the end.”

Catch Matt Sertich on Thursday, July 10 from 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m. during the Hot Lunch Concert Series at Fremont Park: 16th and Q Streets, across from Hot Italian. To buy The Only Way Out is Through, go to Mattsertich.bandcamp.com.

Sacramento’s Century Got Bars Concocts a Modern Throwback on Her New Release, 3

The freeway is a mess on the drive down Highway 99 to Elk Grove, where Century Got Bars is busy putting the last touches on her third solo album—the aptly titled, 3.

On the road, trucks tailgate cars, motorcycles weave in-and-out of traffic, while a woman eating a cheeseburger flips me off for going the speed limit in the slow lane. I’m trying to be patient. I’ll find my Zen and not beat the shit out of my steering wheel in a fit of suburban road rage as the traffic slows to a dead halt.

Since Century sent the majority of her album the night before, I flick on the stereo and have a listen. In an instant, my car is filled with bass, bombarded with “No Private Dancer,” a modern, speedy boogaloo that at once calms my nerves and makes me want to jump out of the car and do a backspin in the bed of the truck in front of me. Track after track, Century’s 3 offers a surprising, fun, unpredictable and eclectic mix of music, from soul to R&B to rock. The 32-year-old MC seems to have found a comfortable spot within the music industry, not by keeping to one genre, but by doing whatever the hell she wants.

Often, my critique of Sacramento rap is that it’s too timid—not that it’s quiet or that it has nothing to say, but that many MCs seem to adhere tightly to conventions, stuck within the confines of gangsta rap or ’90s-style boom-bap. Sacramento rap can be predictable and mind-numbing, if you listen to enough of it.

But somehow, Century’s 3 is none of those things. The album brims with honest, straight-up modern hip-hop songs with local legends—such as the track “RU Mad,” featuring Nome Nomadd and Mic Jordan—but the best part of 3 is the unmistakable ’90s vibe on tracks like “Last Laugh,” with Oakland artist Are Too belting out a hook that takes the listener right back to the days of Cross Colours and Hi-Tec boots while Century raps in a laid-back, introspective tone (like CeeLo, back when he was in Goodie Mob). There’s a lot to like on this album. There’s poetry, humor, earnestness—and best of all, there’s sprawling beauty and good, old-fashioned fun.

When I wind through a few suburban neighborhoods and pull up to Brian “AlienLogik” Baptista’s home studio, “The End,” a clean, energetic track featuring Mahtie Bush, Luke Tailor and maybe the best The Doors sample in the history of rap, bangs from the speakers. By the time Century’s verse, full of well-timed and wry observations (“Quit being bitter, nigga, pick up a book or pick up a Nook”) my face is plastered with a silly grin.

Usually when people say ‘90s, they think golden era/boom-bap, but your album is different—more SWV and TLC.

I’m thinking R&B. I’m thinking also boom-bap, but then I was listening to Rage Against the Machine. I was listening to Nirvana. I was listening to Portishead and all kinds of people. Neo-soul. D’Angelo. I remember in the ’90s, you could be at a family reunion and one moment you would hear DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince, but then the next moment you’re hearing Arrested Development and then the next moment you’re hearing Beastie Boys. Everything was eclectic. I’m a huge Alanis Morissette fan. I have Jagged Little Pill on rotation!

But that’s probably because you’re gay.

But you know what’s funny? I’m one of the real not-stereotypical gay people. I don’t hang in gay crowds and in gay clubs. I’ll go, but I like being around all people and I happen to be gay. I don’t really fall into all that. But having all that stuff played for me as a kid opened me up and it made me want to find out about other people. I just love everything different.

There’s no money in music. Why do you do it?

Because fortunately my mother raised me to have a day job. I work for Corporate America. One of the things my mother told me is, “Just know that if you ever quit your job, I will never listen to any more of your songs.” And I believed her. I have a 40 hour-a-week job to bitch about. I don’t ever have to bitch about music. I do this because I love it.

What if this album blows up? Would you quit your job?

I’ve been shelved. So I’ve gotten all the way to where they’re going to pick up your album to give you a recording contract and got shelved. So to me “big” would be getting someone to offer me distribution, even just in California. That would be a big look for me. If I could do that and not work, then great. Plus, I got student loans. Nobody has time for advances and all that crap from the labels when I owe my whole college education.

Did college teach you anything that you need to know now?

I think the environment of college did. I don’t know if the classes did. I hate to say that. Also, I went to school for audio engineering at The Art Institute of Atlanta. I got to learn a lot about what good quality sound sounds like. So when I found AlienLogik, he knows the fundamentals of what I learned in Atlanta. So I can mess with this dude and know he will not have me out here sounding like, “Did they [record] this in some shallow cave with a curtain over them?”

People contact you all the time asking for verses when they haven’t heard your music.

That happens a lot and I’m very nice to people when they do that. I don’t like it when people hit you up and are like, “Hey, you look dope. Can I get a track?” You didn’t even take one minute to Google my name. You didn’t even try to press play on the song and you’re asking me for a track?

Why do people do that?

Because people don’t want to work for anything. That’s all that it is. It’s sad because there are a lot of local rappers that have this mentality and that’s what you’ll hear on the song “The End.” We’re talking about people that have this mentality that everything should be handed to you. If someone comes to me and says, “Man, I’ve played Midtown Marauders or I played Forget Today, Remember Tomorrow, would it be OK if we [collaborated] on something?” I’m hella not rude.

How important is it to have female voices in hip-hop?

Uh, critical. I want to make sure I dispel this whole thing: I remember one time somebody said “She’ll slap me if I use the word ‘femcee’ when I talk about her.” But, look, it’s not that. Of course I’m proud to be a female and also be an MC. What’s happening is women are being conditioned to think that’s dope. I see tight females that are rappers that put “femcee” next to their thing. You’re putting yourself at a disadvantage because they’re putting you in a box. I don’t want to be a femcee. I want to be an MC that if you named your favorite rappers, period, I would come up. But females making their way through hip-hop is so important because the female’s life, the struggles that we incur … I mean, God, you guys have it easy. Do you know how many doctors’ appointments we have to go to?

Is it frustrating to spend a lot of time on an album and have not a lot of people download it or buy it?

It did when my head was in the wrong place. I was thinking more like, “Look at me!” like a lot of these people do. But I have this category. I have “Look at me!” and “Hardworking and fulfilled.” The “Look at me!” doesn’t do anything but give you five seconds of attention. And then when it goes away you’re mad because you don’t have the attention. Once I stopped caring about what everybody thought, that’s when everybody started listening.

How will this album be received?

They’ll like the fact that it’s so eclectic. There’s something for everybody on here. Everybody can feel involved. There’s not a lot of sexualized songs or a lot of straight up profanity or making one group feel bad about themselves. It’s just a happy album. Let’s get it moving. Let’s get it dancing.

Talk about Sacramento.

I want Sacramento to realize how good they have it. I’ve come here and I’ve never felt so welcomed. It’s hard to go back to your own home and everybody just knows you as the person they went to high school with. I don’t think anybody except my close family and best friends [in Detroit] have downloaded that album. And that’s hard. Because it shaped me. And I want to let them know that I’m always going to claim them even if they don’t claim me. But like the saying goes, “A prophet isn’t recognized in their own home.” But, guess what? In Sac they are! There’s a whole bunch of prophets that are recognized in their own home! And they don’t see how good they have it.

Do you feel the effects of sexism or homophobia here?

In Sac? No. God, I love Sac.

The release show for Century Got Bars’ 3 is at the Press Club Thursday, June 19. Doors open at 9 p.m.; Century’s set starts promptly at 10:30. Hosted by Andru Defeye and Miss Ashley w/D.J. Epik, Mic Jordan, Mahtie Bush, Luke Tailor and Petro. Tickets are free before 10:30, $5 after. Facebook.com/CenturyGotBARS for more info.

Backstreet Boys, The Fray

Ace of Spades, Sacramento

Wednesday, Dec. 4, 2013

What could be sadder than a 38-year-old man going to a Backstreet Boys concert by himself? Well, to be honest, probably a lot of things. For instance, that last copy of Zoppi’s Suspended CD that remained untouched at The Beat since it was released in 2000 is pretty heart-wrenching. And images of the abandoned Ferris wheel at The Neverland Ranch are downright depressing. So, I dunno, there are things.

But here’s the weird part: Right when I heard Backstreet Boys were coming to Ace of Spades (and that the show was sold out), my first thought was, “I need to cover this” without even questioning for one second why in 2013 I would actually want to see the Backstreet Boys. And even weirder: After a bit of thought, it dawned on me that I don’t know any of the members in the Backstreet Boys. And the only song I can recall is the one that goes, “Backstreet’s back alright!”

Which is when my existential crisis kicked into high gear.

“Why?” I thought. “Why would I beg to review this concert? What is the point? Why is this band important to me if I don’t even know the members or any of their songs?” Even more difficult to understand was at the end of every question came only one answer: BACKSTREET BOYS. It made no sense that I could think no further than that, as if my mind was somehow clouded by their stardom.

Why do I want to go to this concert? BACKSTREET BOYS.

Who are the members of Backstreet Boys? BACKSTREET BOYS.

What is the … BACKSTREET BOYS.

It’s like a satanic curse that landed me in a hellish underworld of dramatic finger pointing, waxed male nipples and stylishly choreographed dance moves.

However, because I am a professional, my research began, and through that I learned that Justin Timberlake is, in fact, not a Backstreet Boy. And I found out there’s a Backstreet Boy named Howie. And I guess one of the guys, Kevin, is back (hehe, get it?) and Nick Carter, the tall baby-faced blonde with porn star qualities, had a cameo in Edward Scissorhands … So, armed with as much Backstreet trivia as my brain could handle, I set off for Ace of Spades.

A band called The Fray took to the stage at 8 p.m. I actually listened to a few of their songs before seeing them live—enough to determine that their whitebread form of rock ‘n’ roll sounds like music a menopausal woman might listen to right when she says, “Fuck it,” and tries heroin for the first time. The Fray went on for an hour-and-a-half. A long, grueling hour-and-a-half that I mostly spent standing next to Mark S. Allen, analyzing his beautiful and flawless face. If that ageless man isn’t handsome I don’t know who is. Anyway, the most interesting part of The Fray’s set was when two bleached blonde soccer moms fistfought by the bar.

When the Backstreet Boys (there are five of them, I learned) finally took to the stage, my life force had been uncomfortably moistened by The Fray’s steaming pile of music. However, I was quickly intrigued by their presence. They looked healthy and spry, like a boy band should. And their voices, while a little on the low end and muffled by the loud backing tracks (yup, no live band), sounded competent enough. They hit their melodies and demonstrated complete control of their voices (let’s be honest: not even Lauryn Hill can do that anymore). And all that while dancing in tight pants.

After a few classics and a performance of their new song “Show ‘Em (What You’re Made Of),” a surprisingly sparse and catchy single, Nick Carter announced that the Backstreet Boys aren’t just a boy band. “We can play instruments, too,” he said, which took us down a long, boring road of acoustic pop songs.

To be honest, all their songs sounded the same, but I sort of enjoyed standing there in that fog of Axe Body Spray, watching good-looking people sing and dance—if only for the change of scenery. It was certainly a change from watching death metal bands while standing in a crowd half-filled with methed-up neo-Nazis.

Halfway through the Backstreet Boys’ set, I felt the tip of a fingernail grinding into my shoulder. It was a woman, probably in her 50s, wearing an obscene amount of eye shadow and blush.

“Hey, you need to move because I’m trying to keep an eye on my daughter,” she said.

“No,” I said. “There’s no room for me to move.”

“I’m trying to watch my daughter,” she shot back, pointing to the teenage girl in front of me.

“If you cared about your daughter you’d leave the bar and stand with her,” I said.

“How dare you?” she yelled, as if nobody had said no to her in her life. “Why won’t you move?”

I grinned, because the answer, of course, was BACKSTREET BOYS.