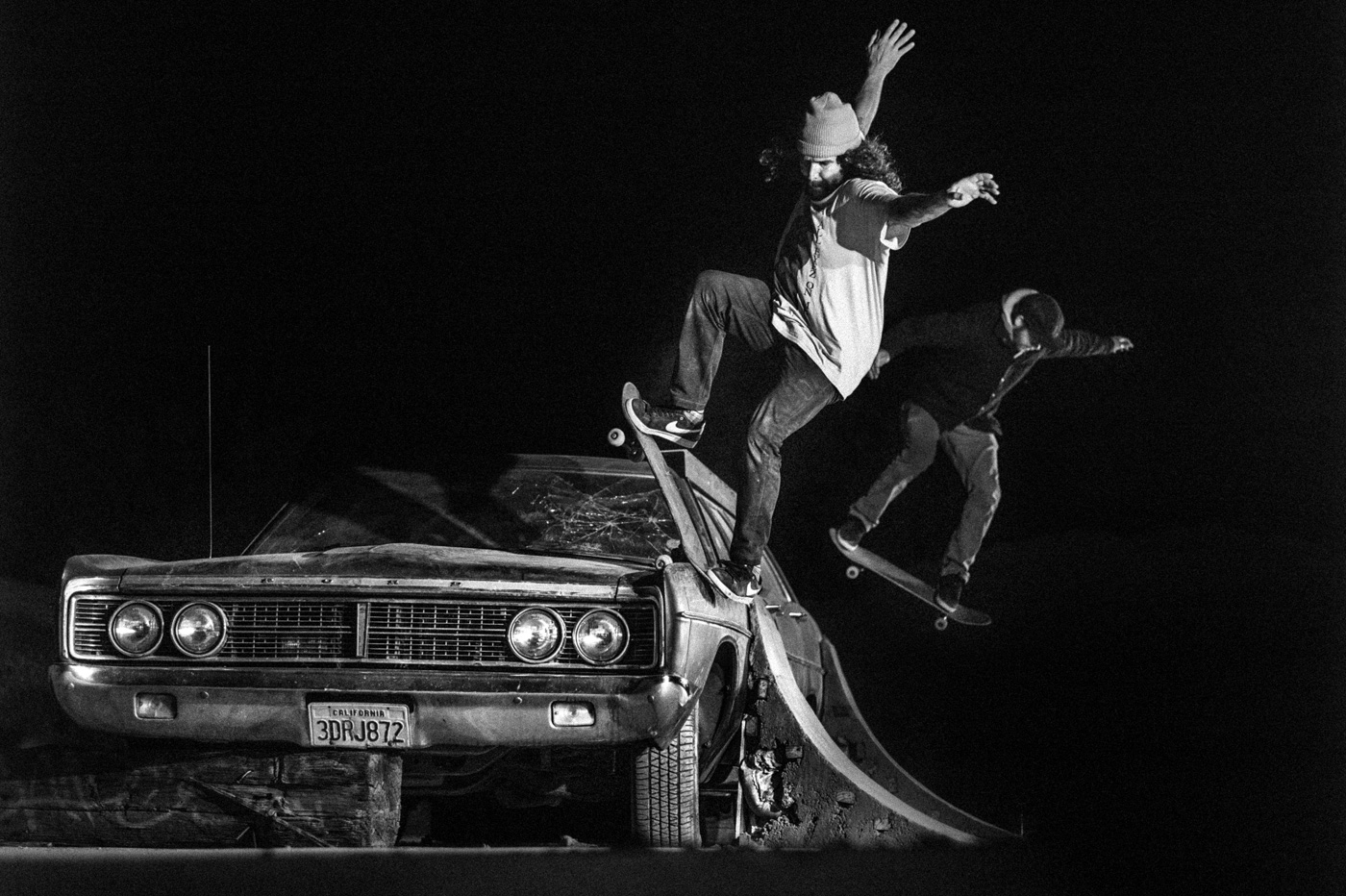

Eli Williams | Kernside, California | Photo by Anthony Acosta

Eli Williams | Kernside, California | Photo by Anthony Acosta

Thomas Campbell is a Renaissance man for misfits. He is a skater, a photographer, a filmmaker, an artist and a bunch of other shit. Most people want to do one thing as well as he does all of these things. Growing up in Dana Point, California, where he says “pretty much every boy and girl rode skateboards,” Campbell was exposed to it at a young age, something he credits with sparking his career and creativity, which for him is one and the same.

“I started skateboarding when I was 5 and now I’m 50 and I’m really happy for where skateboarding is,” he explains. “I don’t care about contests or Olympics or any of that shit. I just really like that kids are open-minded and skating wildly amazingly. That’s such a cool moment, you know?”

Uncompromising and singular, he says he “cannot bring [himself] to not make the thing that [he wants] to see.”

“I will make an hour-long film and not give a fuck,” Campbell says. “However it falls, it falls.”

In the past, skate media was elusive, and when you actually got your hands on some, you held onto it until the end of time. These days, however, skate videos are readily available. Videos of tricks thought to be impossible 20 years ago are a YouTube search away. Yet, somehow, it all feels so sanitized, corporate and clickbait-y.

Ye Olde Destruction, Campbell’s newest film, is none of those things. Raw, energetic and lively, it could just as easily be playing in the MoMA as on a VHS player behind the counter of your local skate shop. It is an art film for skaters, and a skate film for artists.

Imagine if Larry Clark and David Lynch took some shrooms and went skateboarding together. Now imagine that in black and white.

Ye Olde Destruction will be premiering in Sacramento on Feb. 6 at Midtown BarFly. The soundtrack will be scored live by Tommy Guerrero, Matt Rodriguez, Lee Bob Watson and Josh Lippi. Be there. And bring your board.

Photo by Jai Tanju

How’d you initially get started within skateboarding? Was there any particular incident that drew you to it or was it just kind of a natural thing?

When I was a kid in the ‘70s, it was just kind of a boom, and where I lived there were hills, and my street was a really good one. Everyone would come to skate on my street. There was a quarter pipe back at the top of the hill, and at the bottom of the hill there was a drainage ditch.

What was it like making A Love Supreme [Supreme’s first skate video, released in 1995]? And how’d you initially link up with Supreme? Back then, every hypebeast wasn’t lining up for their T-shirts, they were just a skate shop.

I was skating with those guys and shooting pictures of the guys that rode for Supreme, and I was friends with the guys who worked at the shop. I grew up in California, and I always liked all types of music from punk rock and jazz and indie rock. But when I moved to New York, I dove way deeper into jazz. I love that Coltrane record, A Love Supreme, and I just had an idea and ran it by those guys and they were into it. The day I started filming A Love Supreme was the first day that I ever used the 16mm cameras. So, that was the beginning of my journey that I’m still on today …

What inspired you to shoot in 16mm?

I just feel like it’s a super visceral medium; it’s not lo-fi, it’s not super hi-fi. You have this nice area where you can get a lot of emotions from the film grain and the way the film dances. And I feel like it captures an emotional range really well. And it’s been my dancing partner. It does a lot for mood and ambience, and film innately adds a lot of dimension. It’s probably coming to an end because the problem is you can still get film, but the people that fix the cameras are dying and/or retiring and there’s no one to fix them. It’s kind of going toward obsolescence. Like one of my main cameras, I can’t get fixed. I have this film and then I have a surf film coming up that are predominantly [16mm]. Ye Olde Destruction is probably 90 percent. There’s, like, the drone footage and a few minor things that weren’t on film.

Thomas Campbell getting inside trunk shot | Photo by Jai Tanju

The mix of skaters you had was really diverse. You’ve got old schoolers like Ray [Barbee] and you’ve got people like Ishod [Wair] who are much more modern, technical skaters. Did having such a mix of different skaters affect the making of the film?

A lot of how I see the skateboarding is just like whatever’s there, just go skate it, you know? And that’s how I’ve always looked at it. And I think, like, the divisiveness in the ‘90s when there was tech skaters, gnar bowl skaters and vert skaters.

And now you see people like Evan Smith that approach skating like they don’t give a shit. They’re just, “I’m gonna wall ride, 180 out off this thing, then I’m gonna switch crooked grind this handrail.” That really inspired me to want to document it more. I always liked the idea of just getting unique people together and seeing what can happen from people being together. It really had a lot of people who personally wanted to be there. You know, skating DIY in general is not super gnarly. What you see in a magazine is really less than 1 percent of how people normally skateboard. Most people just aren’t very good at skateboarding and are not hitting super gnarly stuff because people don’t have that skill level. Is it cool to see guys at the highest level pushing things into stratospheric areas? Of course it is, but it’s not what the mass of people are doing. And I think that laughing and having fun with your friends and doing stupid shit is what skateboarding is about.

John Worthington | Delano Pool | Photo by Thomas Campbell

You also made a photo book that accompanies Ye Olde Destruction. Did making the book come naturally in the making of the film or were there additional challenges you had to face?

I just always wanted to make a book with it because I knew in the making of the film, I was getting all my friends, like Brian Gaberman and Jai Tanju and French Fred and Arto Saari and different people to come on the trips and they’re all insane photographers. I just knew we were gonna end up with just an incredible body of images. I liked that format, too, so people can have something physical to connect them with the project and I think it turned out really cool.

How do you think social media has changed the face of skate photography and filming?

It’s changed the face of everything. I think kids are communicating on a much shorter wavelength. I’m 50. I have a much different idea of what I want to do with my time than the kids now. And I think the length of my film really speaks to that. Like, I know a skater that went, “Uh, I can’t really watch things that go over four minutes.” I could go into, “I think that that’s fucked,” but it’s their life, and they’re impacted by the way things are going.

And I look at the analytics on my films online and people have such short attention spans. I’ll make little clips that are three to seven minutes and people generally don’t watch over a minute of them; things are just simply changing and that’s all there is to it. And I hope the best for everyone, but I’ve just got to do the things I got to do.

Al Partanen | Photo by French Fred

It’s funny you say that; having the artist’s vision where you don’t compromise for anything. Going off of art, how did you initially start painting?

Oh, I mean, I think just being an artist is gained from being in skateboarding. You know, like getting Thrasher and seeing Neil Blender and Todd Swank’s work, and just being, like, “All those guys are having fun. I wanna have fun. Let’s try it.” I think skateboarders have a lot going for them just because of the nature of skateboarding. You fall and then you fall and then you fall. Then maybe you make something and then you fall again. And failing is normal. If failing is normal, then that’s cool, because life is hugely about not succeeding. So you’re just psyched on the process, and you know how to persevere when you’re a skateboarder. I honestly give everything in my life to skateboarding. You know, what happens if I fucking play tennis? So yeah, my art really came from that and my approach to everything came from my inspiration from being in that culture. There’s not that many things that are that physically visceral that ground you in that way. You have actual trauma, you know? You have no one to blame; it’s you not nose-grinding properly. It’s you figuring out the weight distribution and how your tricks are going to be performed. You’re like, “OK, I’m going to be up there. I need to put my weight on the back foot and have the pressure more on the toe side. And then the front foot kinda does this.” But it’s problem solving and it has consequences. And then it’s tied into so many creative outlets like music and art and graphics; there’s just so much dimension.

What’s inspired you lately?

I think what’s probably inspiring and de-inspiring me the most is our current situation on this planet, where … our world views [are] nationalistic. We’re living on a planet, a round sphere, and we’re fucking this planet up. All these imaginary lines that are drawn all over the Earth by corporations that call themselves companies, we have to get beyond that and look at this Earth as the cellular process that it is. And people are so worried about being Americans and not being humans on the Earth or any country for that matter. We need to get beyond it. The movie’s not overtly political, but it has a dystopian feeling to it and that fear and tension is expressed within it. Our current political scenario with this fucking Cheeto in office and all this shit, it’s definitely inspiring me and motivating my creative process and my want to communicate and express about what’s going on. I have a 3-year-old daughter, and I’m just thinking about her future and I’m scared. We need to talk about it. It’s important.

Omar Salazar | Kernside, California | Photo by Anthony Acosta

Catch the Sacramento premiere of Ye Olde Destruction, with live score provided by Tommy Guerrero, Matt Rodriguez, Josh Lippi, Jason Boggs and Lee Bob Watson, at Midtown BarFly (1119 21st St., Sacramento) on Thursday, Feb. 6 at 8 p.m. DJ Juan Love (AKA John Cardiel) will also provide tunes for the event. For more info, go to Facebook.com/tommyguerreromusic.

**This piece first appeared in print on pages 20 – 21 of issue #310 (Jan. 29 – Feb. 12, 2020)**

Comments