Photo by Yoon Kim

Photo by Yoon Kim

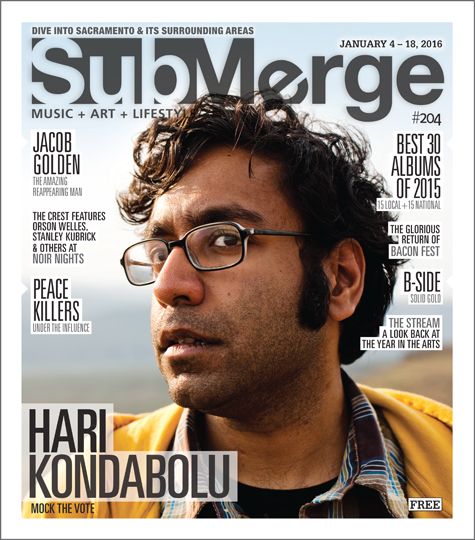

In most circumstances, political dysfunction lends itself beautifully to the joke-writing comedian. It’s a plucking ground for material that elicits strong feelings among a large audience, so it’s ripe for comedic dissection. But for Hari Kondabolu, in this particular moment, it’s almost too much to keep up with.

He’s recording his second live album less than a month from now in Portland and would like to incorporate the election heavily into his set, but as he irons out his material and prepares it for the road, that cast of characters just keeps on making headlines. From Donald Trump riffing jovially about Mexicans and Muslims to Jeb Bush watching his pile of money disappear alongside his poll numbers, the whole thing is still so fluid.

“This election is bringing things to the surface constantly because of the extremes,” Kondabolu told me by phone. “By the time [the album] gets released, hopefully in the spring, I don’t know who’s going to be relevant still. I want to write stuff that’s not going to disappear with the election cycle while still covering the now.”

The clown car remains full, and it’s hard to know exactly where it’s headed. Kondabolu is doing a short tour leading up to the album recording so he can feel things out in front of a few live audiences before he presses record. Two of those shows will be at the Sacramento Comedy Spot on Jan. 23, 2016.

“I’m hoping by Sacramento I’ll just be running the set,” he said. “If I recorded it in Sacramento, it would still be a solid album. I want to give them a great show that has a few moments that are flexible. I think that’s kind of fun.”

While the election itself will surely be a part of Kondabolu’s act, his real interest is in the broad issues that surround the political jockeying.

“Politics is like the game,” he said. “It’s the sport. The things I care about are the bigger issues like racism, immigration, homophobia, sexism, transphobia.”

Immediately prior to becoming a full-time comedian, Kondabolu was an organizer for immigrant rights in Seattle. He played open mics and clubs at night because he enjoyed it, but organizing was the primary recipient of his energy. It was his job.

But over time, Kondabolu’s comedy caught momentum in Seattle. He went from an “unknown open miker to the hottest comic in the city,” according to a 2007 Seattle Times article. He was invited to perform at HBO’s prestigious U.S. Comedy Arts Festival and appeared on Jimmy Kimmel Live! shortly thereafter. With that head of steam, he’s been a rising comic ever since, with a following far beyond his starting point in the Pacific Northwest.

But in spite of his pivot to comedy, Kondabolu the immigrant rights organizer is still very much the man on stage.

“I’m doing an elevated version of myself,” he said. “I’m a very political person and I can’t not view the world that way. My lens is a politicized, radicalized lens.”

And yet, social change is not Kondabolu’s priority. He’s here to make people laugh, and he does so by picking apart the things he knows and cares about. If people are forced to think about something important in the process, he’s cool with that. But it’ll never be the impetus for writing the joke.

“It’s dangerous to have that mindset while you’re writing,” he said. “There’s an ego that comes with being a performer. If you add that self-importance to it, it’s going to affect the quality of work and it won’t let you write from an honest place.”

I asked him what satisfies him most on a purely human level: Pushing for social change or making people laugh? His answer was swift and clear. He wants to make people laugh.

“I’ve had audiences that weren’t laughing, but they’d come up to me after and say how important the work is that I do,” he said. “That doesn’t make me feel good! I’m a comedian and I love and respect the art form. I could have become a lecturer or done something else!”

My first exposure to Kondabolu’s comedy was a YouTube video tweeted by journalist Jay Caspian Kang, whom I learned during my interview was a classmate of Kondabolu at Bowdoin College in Maine.

The video was a two-and-a-half minute clip about people who threaten to move to Canada in the wake of unfavorable political situations.

“Man, if a Republican president wins, I’m moving to Canada,” Kondabolu says before pausing. “You’re not fucking moving to Canada! I’ve heard this shit before. I hate to break this to you, but Canada doesn’t have a special visa for American liberal cowards. That’s not how the immigration system works. What, you think you’re gonna get in on refugee status?” And so on.

I saw that video about a year ago and followed Kondabolu on Twitter that day. Over the ensuing year, the issue of political correctness edged its way to the front of national conversation, mostly as it relates to over-sensitivity in college students.

A recent cover story in The Atlantic carried the following subject line: “In the name of emotional well-being, college students are increasingly demanding protection from words and ideas they don’t like. Here’s why that’s disastrous for education—and mental health.”

An accompanying article explored why some prominent comics are choosing not to play college campuses for that very reason. The article describes the annual National Association for Campus Activities convention, in which comedians gather to audition for lucrative college gigs. Playing it safe is the name of the game, because NACA is looking for comics whose sets won’t “trigger or upset or mildly trouble a single student.”

As a former organizer whose politics are weaved into in the DNA of his comedy, what does Kondabolu think of comics like Bill Maher and Jerry Seinfeld avoiding college campuses because the kids allegedly can’t take a joke?

“That’s what old people sound like,” he said. “Your job is to reach people. If you’re not able to make [young people] laugh and find things that can have them thinking, why are you relevant?”

Kondabolu contrasted those established comedians with the late George Carlin, who he said remained culturally interesting and challenging across demographics all the way up to his death. He says it’s lazy to simply write off a whole generation as sensitive babies.

When Kondabolu plays colleges, he’s typically invited through a back door by a professor or a social/political student group rather than the folks in charge of campus activities. He also resists folks who have held him up as an example of how political correctness can coexist with stand-up comedy.

“I’m not politically correct,” he said. “Maybe you’re not offended because you agree with me, but that doesn’t mean I’m not offensive. People walk out of my shows and they’re not walking out because I’m ‘politically correct.’”

Kondabolu, who grew up in New York the son of Indian immigrants, says that what some people like to call political correctness might really just be “well thought out progressive opinions.”

Donald Trump has built a massive lead over his fellow Republican candidates by denouncing that very political correctness. Meanwhile, Kondabolu continues to write jokes and refine his act with one eye on the screen as his album-recording show inches closer. Let’s see if anything fun happens between now and his sets in Sacramento.

Catch Hari Kondabolu Jan. 23, 2016 at the Sacramento Comedy Spot, located at 1050 20th St. Shows are at 8 p.m. and 10 p.m. and tickets are $15. For tickets and more info, check out Saccomedyspot.com.

Comments