I’m pretty sure we all had our own Tower Records. Growing up, mine was in the East Bay suburb of Concord off Willow Pass Road. Later, it was on Main Street just up the way in Chico.

Where was yours?

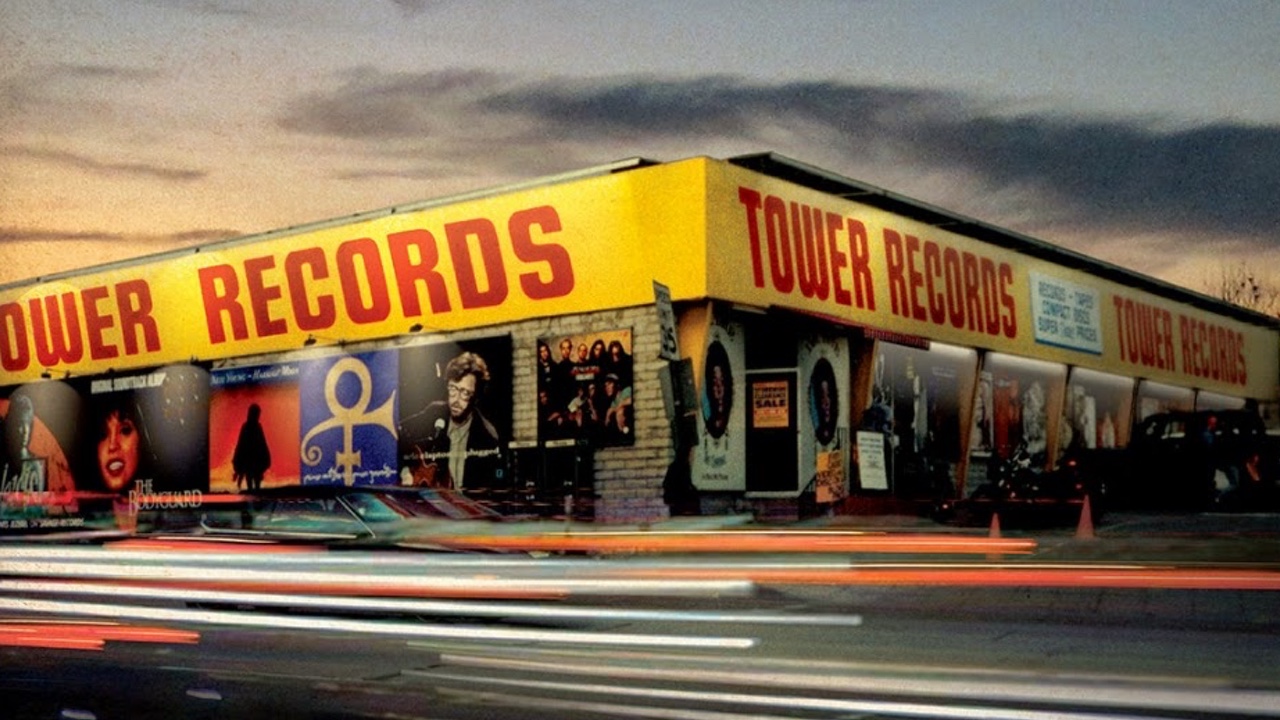

Suffice to say that no matter where your Tower was, it hasn’t been there in a good long while. Having officially closed their doors in 2006, the once-mighty, Sacramento-bred chain exists now only in skeletal remains: faded price-tags on used LPs and building signage left behind in apparent tribute. That doesn’t mean we’ve forgotten about Tower, or any of its record store brethren that also entered into eternal slumber over the past decade. No, we remember, and fortunately so do Colin Hanks and Sean Stuart, director and producer, respectively, of All Things Must Pass, the first documentary chronicling the rise and fall of Tower Records.

Both natives of Sacramento and best friends since age 12, Hanks’ and Stuart’s Tower was on Broadway, an “ambitious bike ride” from their East Sac boyhood homes. In those formative years each fostered their own love of all-things music, with experiences now reflected upon with nostalgic fondness, from buying Tom Petty tickets at Tower in 1990, to frequenting The Beat at its Folsom Boulevard location. And it’s because of those experiences that we now have a lively, entertaining and heartfelt film to tell the tale of America’s—or perhaps the world’s—greatest record store empire. All Things Must Pass draws upon countless hours of interviews and archival footage to spin a yarn that feels both familiar and fresh, starting with Tower’s humble, pharmaceutical beginnings in the 1940s, and ending with its spectacular crash in the early part of the 21st century. Featured prominently alongside Tower’s founding father Russ Solomon (a gregarious, almost mythical figure) are his many valued and beloved Tower compatriots, as well as the likes of Elton John, David Geffen, Dave Grohl and Bruce Springsteen. The end result is one of heavy sentimentality that will likely leave you reminiscing about the good ol’ days, but at the same time you’ll be smiling by way of a Japanese twist.

Colin Hanks, Sean Stuart and Russ Solomon were good enough to speak with Submerge in anticipation of All Things Must Pass screenings at the Sacramento International Film Festival at The Tower Theater on April 25 and 26, 2015. Keep an eye out at Towerrecordsmovie.com for announcements of future screenings and to learn more about the film.

How was it that you became interested in telling Tower’s story? What made you want to take this on?

Colin Hanks: As the stores were closing in 2006, an old family friend of mine from Sacramento, named Nancy Comstock, was in New York on business and I took her out to dinner for her birthday. She had walked by the Tower on Lincoln Center on the way over, and the beginning of the dinner conversation was just what a bummer it was that Tower was closing. And I had known that Tower was a Sacramento company… I had my own personal connection to the store, buying concert tickets and CDs and cassette singles and stuff like that. And at the end of the conversation, sort of in passing almost as an aside to herself, Nancy said, “And to think it all started in that little drugstore next to the Tower Theater.” And I said, “Excuse me, what?” I had not heard about that. I didn’t know how Russ started selling used 78s in ‘41. That was as close to a light-bulb moment as I’ve ever had. I said, “OK, that’s a documentary.” If Russ’ journey starts there, 1941 classic Americana, soda fountain drugstore roots, and it ends in 2006 with him shuttering 180 stores across the world, that’s quite a journey. And then once I did a bunch of research and saw that no one else had really tackled that as a stand-alone feature, I sort of naively said, “I want to make a documentary about Tower Records.”

Sean Stuart: Colin sat me down in the fall of 2007 and basically said, “Hey, I had dinner with a friend, we were talking about Tower Records, and she told me that this thing started in the back shelves of a pharmacy,” and then went on to give me a five-minute pitch. And by the end of it I was just like, “This is a no-brainer.” Regardless of the fact that we get to jump into something that has civic pride for us—a company that we know very well that came from our hometown—beyond that this is a story that I think will resonate with everyone. It’s music. It’s how we consume music. It’s the erosion of brick and mortar in our culture. It just felt like something interesting and compelling.

Russ Solomon comes off as such an engaging and larger-than-life personality in the film. What was it like working with him, and did you get a chance to interact beyond the interviews?

SS: Oh yeah, a ton—there’s no way you can’t. Colin and I have spent a lot of time with Russ over the past six, seven years. Interviewing, but even more than that. Honestly more of a friendship level. Patti [Drosins, Russ’ wife] and Russ to me at this point are a little bit like hanging out with family. God, I pray that I’ll live to be 90 years old someday and be as quick as he is. I don’t know a lot of 90-year-olds, but the guy, I mean literally, his memory is a steel trap. We’ll be sitting there and you’ll say one little thing and he’ll go into a five-minute story about something that’s more impressive than anything I can muster up at the wise old age of 37. He is an impressive, impressive man. We learned so much from him. There were times when we’d be sitting there just talking with him, no cameras, nothing rolling, and it was like graduate business school. Life Lessons 101 on how to run life and how to treat people. It was just really unique and a wonderful experience.

CH: We approached him in 2008. I didn’t know him, but I knew of him by that stage. So we sat down and met with him and instantly I was at ease. I didn’t know what he was going to say, and I found him to be the pleasant, jovial man that he is. I mean within two seconds of sitting down with him I said, “OK this guy’s a total cut-up.” He’s a great character. At that point he had also insisted that it wasn’t just his story; that it was really the story of all the people that helped build the store from the ground level.

What are your personal views regarding the downfall of record stores? Do you think Tower was unique in how quickly it went from riches to rags, or is this a story that relates to the record industry in general?

CH: Let me narrow this a little bit. The film is not meant to be a documentary about the fall of the music industry. It is meant to explain and debunk the myth that the Internet killed Tower Records. Now, Tower is a good example of the first sort of casualty, if you will, of the death of the music industry. But I’m in no way saying that record stores have died. Because they haven’t. But what I am saying is that record stores as we knew them—in 1999—are dead.

So what I really wanted to do was to explain to people what happened to Tower, and why Tower went. Specifically talking about Tower, it is, quite frankly, gross over-expansion into markets and countries they had no right being in. In countries whose economic structure and population would have never supported such large-scale stores. And also the company’s own mismanagement once the banks took over. They could have maybe closed a bunch of stores and kept a couple open…close all the ones in the suburbs, keep Sunset, keep San Francisco, keep New York—but they didn’t do that.

In regards to the music industry on the whole, we examine certain things the industry did that didn’t help anyone. The biggest issue being [that] they lost an entire generation of kids when they stopped selling singles. We wanted to, in a larger context, be able to explain these certain things that helped set things in motion, so when you get to 1999 and 2000, the train has already left the station.

SS: As the title says, “all things must pass.” I think that we as human beings open the door for new technologies and new ways to consume [the] old. It’s the same way the printing press went. It’s an inevitable thing in a lot of ways. And I think the movie really does explore one business that happens to mirror its industry’s demise. But I think that there’s a lot of good to be seen in how we consume music now…you embrace it, and at times try to fix it.

The archival footage and photography that runs throughout the film is fabulous. How’d you go about the process of unearthing all that?

CH: Russ donated all of his personal collection of memorabilia to the Sacramento Historical Alliance, and we had access to his archives. All the people we spoke to in the film also gave us their own photographs, their own home movies; we licensed some footage; we paid for and digitized some footage; we were sort of de facto treasure hunters for about five years. The footage of Elton John [shopping for records at the Sunset Tower in the ‘70s] has really popped in a lot of people’s minds as this great find, and the guy who owns that footage did not shoot it. The guy who owns that found it in a dumpster 20 years ago and now it’s his.

SS: Part of the biggest battle of [making this film was that] you can go get interviews, but now what brings those interviews to life? Because no one wants to stare at talking heads for 100 minutes. You really have to be able to paint the picture to go with it.

How were you able to pare the film down to 98 minutes? Felt like it could have easily been three hours.

SS: It could have been a mini-series. [But] it’s kind of one of those things that presents itself. You end up starting on this documentary process, and you shape it and mold it and eventually it starts to show you what its personality is, and you end up kind of backing into whatever it needs to be. You don’t wanna force it, and at times you realize you’re getting too precious on certain things that you need to let go of.

Can you speak to the challenges of putting together a documentary in comparison to a feature film?

CH: Well they’re different disciplines under the same banner… I’m much more used to being able to tell a story with a beginning, a middle and an end: here it is, this is what the film’s gonna be, I need 22 days to shoot it, boom, done. This was hard. It changed, it evolved over time. We took five years to shoot this thing…it’s just different. But at the end of the day, we’re still storytellers, and I wanted to make sure that this story was accessible to everyone. It’s not just a film for music fanatics, it’s not just a film for people who only shopped at Tower Records. It’s most definitely for those people, but there’s also a human connection, a family story that we’re telling, both literally and metaphorically, and so I wanted to make the most personal film that I could.

SS: I feel like there are music docs that if you really lived an era, that they move you like nothing else. And I think that’s one of the things that’s interesting about our documentary—it doesn’t really have an era associated [with] it. It spanned five decades, and it’s got such a deep, emotional human story, that you don’t even have to love music to understand. If you’ve ever banded together with other human beings to create something that either succeeded or failed, this movie has something for you. It doesn’t pigeonhole anyone, it’s not speaking to one subject. You may only pick it up because of the music, but once you’re there it’s such a broad story with so much heart, it really speaks to anyone and everyone who watches it.

Lastly, I’ve got to believe the reaction from your screenings thus far has been extremely positive. What are you feeling from people?

SS: I’m feeling like this is truly one of the most beloved companies of the last few decades. It really is something that people bemoan the loss of, and people really have a strong relationship to it. It’s been a great experience to see people connect to this movie…everywhere we go people always have their own story about Tower Records they want to tell us. It’s been pretty special watching it unfold.

Comments