Where did you spend your Fourth of July? A barbecue? That’s pretty sweet. But all the smoked ribs in the world just aren’t as cool as swinging by Jupiter. That’s where the Juno satellite ended up this Independence Day.

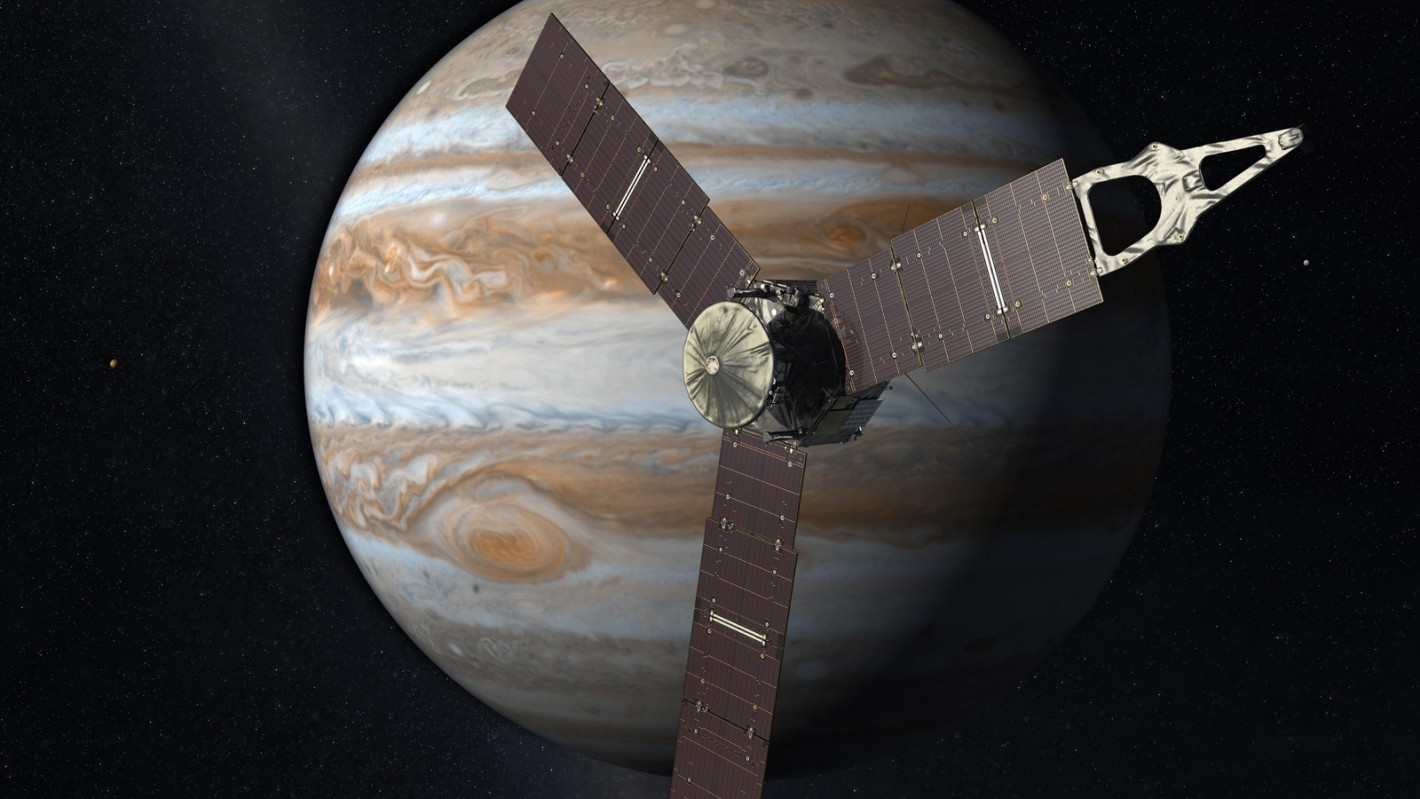

Assuming everything went according to plan (as of this writing on July 3), Juno began inserting itself into Jupiter’s orbit at 8:18 p.m. PDT (don’t know what that would be in Jupiter Time). The process took roughly 35 minutes, and then Juno, a solar-powered spacecraft that would fit more or less snugly into a regulation basketball court, started setting up antennas and probes and whatnots to start broadcasting back to the uber-nerds at NASA who held a press conference at 10 p.m. PDT to let us know that everything went hunky-dory. Again, I’m just going to assume this all happened, because NASA never makes mistakes.

OK, that was low. I’m just jealous that I’m not even remotely smart enough to work for NASA. I just want to go to space really bad so I can meet Yoda. No one will send me. I’m a jerk.

Anyway, Juno, named for Jupiter’s mythological wife who could see through the clouds (according to this nifty Jupiter Orbit Insertion Press Kit I’ve been having a nerdgasm over all afternoon), was launched way back in August 2011. Our world was very different in 2011. David Bowie and Prince were both still with us, Brexit hadn’t become a catchy buzzword, no one would have ever conceived that Donald Trump could be the next U.S. President and I’m not sure which iPhone we were up to, but I’d bet it was the sweetest one ever.

My guess would be that Jupiter of roughly five years ago was pretty much the same as it is now on our Independence Day 2016. I mean, it’s just this giant swirling sphere of gas and gravity with epic storms and a gajillion moons just dominating our solar system out there in the relatively not-so-far reaches of space. It doesn’t have troubling political issues or pop culture or technology posing as pop culture. So why do we want to spend $1.13 billion on getting up close and personal with it?

I honestly don’t know. Even so, I’m all for it. Sure, that money would probably be able to do a lot of good stuff here on Earth. But, well, it’s freaking Jupiter for cryin’ out loud. I mean, seriously, Jupiter.

Juno is a groundbreaking doodad as it has traveled farther than any solar-powered spacecraft has ever traveled from Earth. It will also be the first spacecraft (at least that we know of) to travel as close as 2,600 miles from Jupiter’s cloud tops. As a bonus, it will take the highest resolution photos of Jupiter in our history. The mission hopes to learn more about how Jupiter formed and its evolution over time, which scientists hope will give us more understanding about how our solar system formed. I’m not sure how some high-res JPEGs will do all this, but then again, that’s why I don’t work for NASA.

Juno will then study Jupiter over the next three months, but will not really get down to the nitty gritty of its scientific mission until October. When it’s all done, in February 2018, Juno will go out like a true gangster, plunging itself into Jupiter’s atmosphere in a blaze of glory. In so doing, hopefully sparing the potentially life-bearing moon Europa any contamination of Earthling microbes.

All this is super cool, and not just because I have a raging space boner. I’m sitting here with sweaty palms, anxiously awaiting all these awesome new images to come pouring in. Also, I can’t wait for all the grabby headlines like “Scientists Discover New Clues About Our Universe!” and such.

But other than the cool factor, maybe all that money we sunk into Juno could have some real practical applications. Like, that solar-powered engine … er … thing that was able to propel Juno so far and so fast out into space (it was capable of reaching speeds of 165,000 miles per hour, and at the point of orbital insertion, it would have traveled hundreds of million miles away from Earth). That says a lot for solar power. Like, running a TV shouldn’t be so difficult if we’re able to send a satellite so far. So maybe it can be a thing. And then in five years, we can look back at 2016 and remember when oil dependency was a thing. Or something like that.

Comments