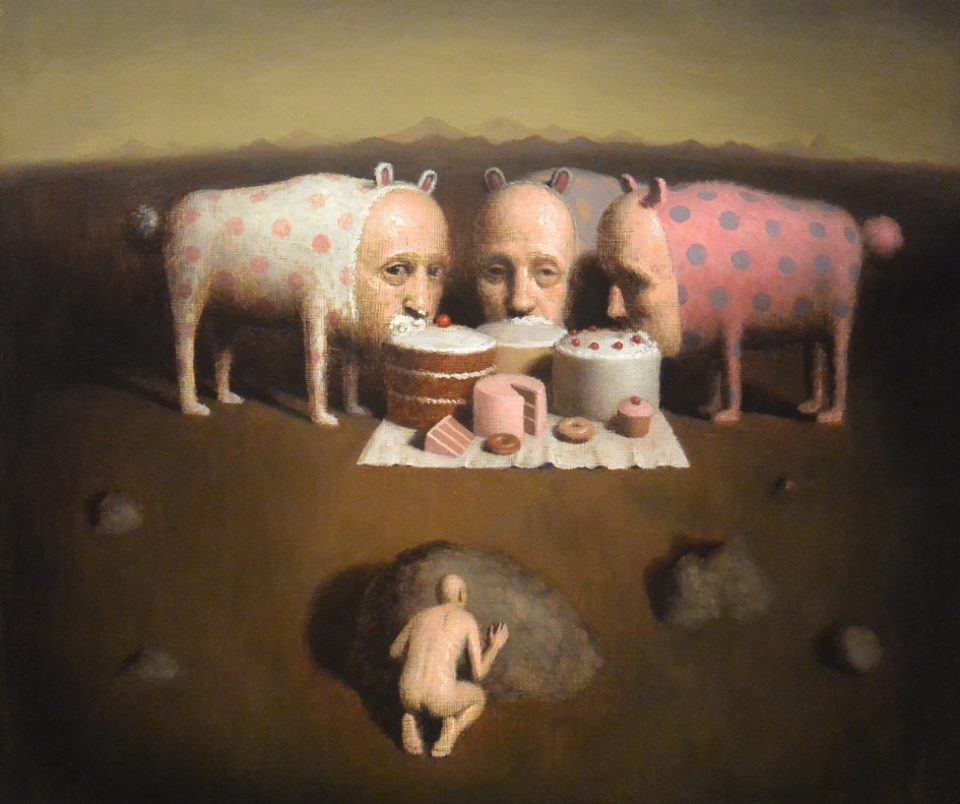

Disillusion from Innocence, 18" x 24"

Disillusion from Innocence, 18" x 24"

Avery Palmer isn’t the dark, brooding figure his paintings make it seem like he’d be. Looking at his work, I thought I’d be meeting up with an eccentric genius like Thom Yorke. While every bit the genius, there’s something pragmatic and humble that sets Palmer apart from the Thom Yorke crowd. Talking to him one Sunday afternoon, he was as unpretentious about his work as any other accomplished craftsman. The experimental jazz musician known as Sun Ra once called himself a pastry chef, noting that “the only difference is that the pastries I’m making are the ones people end up calling ‘music.’” Palmer’s approach, while much more grounded in reality, seems similarly practical. He talks about work like an artisan cabinetmaker or a sawyer might, calling the work back down out of the ether and splitting it into practical terms. “For a long time as a kid I was really into Legos,” he explains. “I’d spend as much time as I could building things with Legos—I feel like that had something to do with my work.”

What Palmer lacks in mysticism, he makes up for in his magical ability to paint eerily constructed scenes, depicting a world of farce and sadness. A world in which the freaks come out. Palmer’s work is a strangely inhabited collection of ceramics, drawings and paintings that serve as windows into a dark and nostalgic dimension. Starting with drawings, Palmer quickly expanded to painting and ceramics.

“At some point, painting seems like it was just a natural progression from drawing,” he says. “I was teaching myself to paint by doing still lifes at home. I’d do little panels—just one a day, and do two or three little objects, it didn’t matter what, I’d just get the light right and paint them.” As time went on, Palmer’s taste for the absurd took hold and shaped his work. He’s featured in the John Natsoulas Gallery’s upcoming show, ambitiously titled The Art of Painting in the 21st Century. I sat down with him to explore his world.

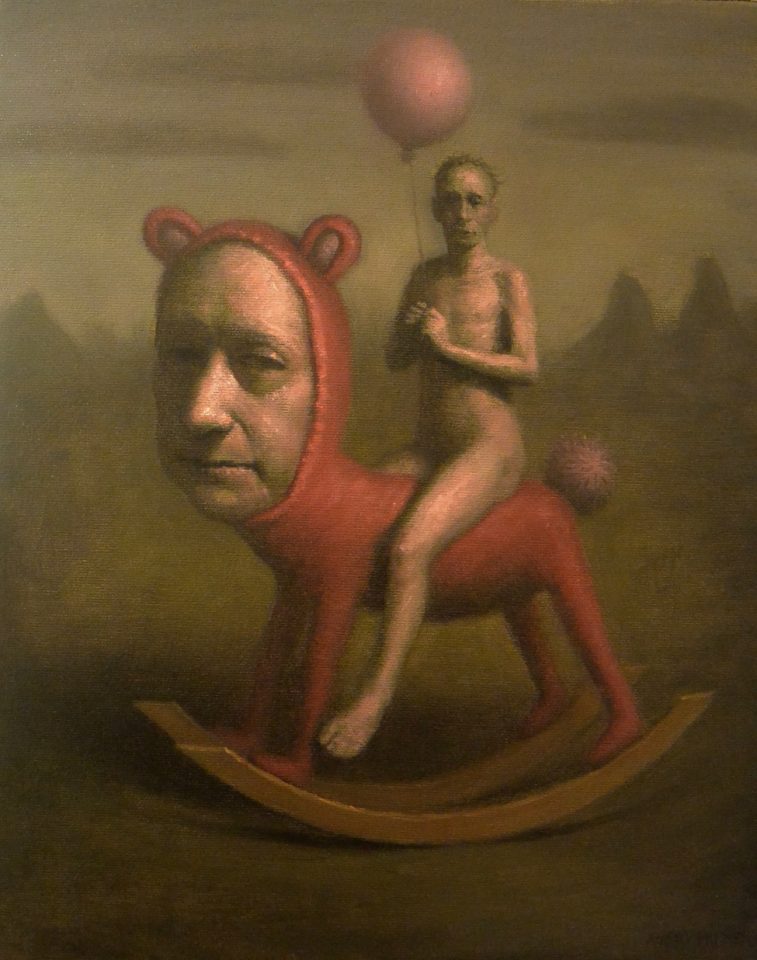

The Boy Who Lost His Way Home, 28″ x 22″

How’d you find art?

As a child I was always interested in things typical little boys were interested in and I’d always draw them, and ended up having a talent at it as a little kid. I guess people were always impressed by my drawings as a kid because I had a better ability to understand the three-dimensionality of things from a younger age, and I got a lot of positive reactions. Those are some of my earliest memories. I always drew as a kid and in high school I started thinking about what I’d be doing with my life, and drawing was the main thing I felt like I was good at. I wanted to see if I could get more serious about it—this was around the end of high school. I became interested in Robert Crumb. I looked at his comics and really loved the way he drew. It’s a cartoon, and it’s simple the way cartoons are, but it had a certain degree of realism to it. In his drawings there was shading and volume more than anyone else who does cartoons.

The Hungry Boy, 20″ x 24″

It makes sense that you’d like Robert Crumb because he really seems to favor the absurd, which is something that I see in your work.

Yeah totally. I think that’s true. I think what appeals to me about Crumb’s work is this idea of sitting down with a blank piece of paper and letting your imagination fill it out and create this world. On your page, a whole world where anything can happen opens up. It made me want to pursue that and see how far I could take it.

Do you sit down with any sort of idea or do you just let it unravel in front of you?

I have an idea and I do some sketching. I have stacks of really rough sketches on scratch paper, and any time I come up with an idea I’ll just sketch some compositional elements. Then I’ll transfer that to the canvas by sketching it with vine charcoal, which is a very simple but accurate sketch, and then I’ll start painting with a thinned-down paint. I’ll start filling in the shadows, and pretty much what you see is what you get. Even though I emulate this sort of Old Master style, my painting is a lot different in that they worked in a lot of layers and I actually usually get everything done in one go.

The Audience, 24″ x 24″

So it seems like you work fairly quickly.

Yeah, I like the idea of being efficient in my process. This idea started with Robert Crumb; I like having something in my imagination and just sort of spewing it out. That’s the thing that I love—the central idea that makes me love art is the ability to transform something in my head into reality and I want that process to be as unhindered as possible. Painting is not really easy, and there’s always struggle along the way but my goal is to be able to have an idea and just kind of let it out very freely. I feel like when a painting takes too long and I have to keep coming back and adding layers, it kind of loses that freshness. I try to keep painting pretty quickly, and if it’s a few weeks later, or something, I won’t end up finishing it because my mind will have moved on.

In your statement, you say that, “The multiplicity of possible readings of symbolisms in my work is central to my concept,” and I wanted to have you sort of unravel that a bit. Are you implying that there’s meaning buried under there somewhere, or are you an outright formalist?

I’d say it’s the latter for sure. It’s purposefully vague. I never want to sort of start out with a story. I just spew my imagination onto the canvas in a way.

Three Wanderers, 18″ x 24″

So is your work kind of divorced from what you’re feeling at the time?

Maybe. I’m heavily inspired by surrealism, and I think there’s a connection there with surrealism where the idea is kind of free association, where the surrealists would just put random stuff out and see what happens, so when I come up with an idea for a piece of art, something will spark an idea—maybe looking at a painting of someone else, and I see a part of it that interests me, and makes me want to borrow something and see what I can do with it by churning it around in my imagination. So I’ll just take some idea and just start sketching and see what sort of objects I can combine. It’s more like a collection of things that I can’t put my finger on, but they’re all interesting to me.

So this show is called The Art of Painting in the 21st Century. What’s it like to be a painter in the 21st century?

I don’t know, actually. I guess it’s not something that I’ve given a lot of thought to. My approach to painting isn’t like that. I sort of look at my process that harkens back to a tradition. The type of painting that I do is very much emulating an older style, so I’m interested in that. It brings you back and gives you a sense of mystery about some other time, so I’m not sure how that relates to the current, contemporary situation.

Persistent Game, 14″ x 11″

And do you see yourself going back to ceramics at all?

That’s what all of my ceramics friends ask me. [Laughs] Right now I don’t have much of an inclination, but it’s hard to say.

It’s not the kind of thing you can do it in your spare bedroom.

Definitely, yeah. I went to San Jose State for grad school. I was there for three years, and it was actually during that time that I started to transition to painting more. One reason for that was that as I developed the ceramic work, I had a thing that I was doing and settled on a style, and people liked it, and it was going well. But the thing about grad school is that it’s all doubt challenging you and making you second-guess what you’re doing and pushing you to the next level. In grad school, I was sort of struggling to figure out what my next step would be. I felt like it was getting repetitive and was frustrated with the time everything took with ceramics.

Then do you see any other significant departures in the future?

I don’t know—it’s sort of just a continuous evolution. I don’t have plans. I’m just steadily trying to improve my skill and my ability to just kind of paint whatever pops into my head without having to struggle too much, a lot of my paintings are relatively simple. I guess one goal that I have is to do paintings that are a little more complex, that have a bit more going on. The reason that my paintings are relatively simple is to keep getting the idea out quickly, so I think that if I’m continually improving myself and the speed at which I’m able to get these things out, I feel like eventually, I’ll be able to even more freely put things down on the canvas as they pop into my mind, so I’ll be able to make more complex paintings as time goes on.

The Visionary, 24″ x 18″

Catch Avery Palmer’s work at the Art of Painting in the 21st Century Exhibition and Conference through March 11, 2017, at the John Natsoulas Gallery, located at 521 First St. in Davis. Find out more about Avery Palmer at Averypalmerart.com.

Comments