Now that Wide Open Walls (formerly the Sacramento Mural Festival) has been running for three years, our city is quickly becoming one of the nation’s leading patrons of urban art. So-called “urban art” combines the aesthetic sensibilities of street art with the familiar imagery of pop art, and uses techniques from both. One of our local leaders in the artform is Sacramento-based artist Brandon Gastinell, who brings a street-art inspired, maximalist aesthetic to pop art prints.

Gastinell’s primary compositional technique is digital collage, which he uses to produce surreal, often gory portraits of celebrities and regular people alike. Inspired by Andy Warhol’s Polaroid portraits series, Gastinell blends fantastic imagery with the inherent realism of photo collages. Life Aquatic, for example, depicts actor Bill Murray in his familiar red beanie from the titular Wes Anderson film. Rather than just reproduce or color swap the photo like his predecessors, Gastinell’s take on the pop-art portrait has dandelions sprouting out of Murray’s head, now detached from the beanie floating above him. The texture, too, has been subtly altered, making for a somewhat blurry, dreamlike finish that accentuates the whimsical plant designs.

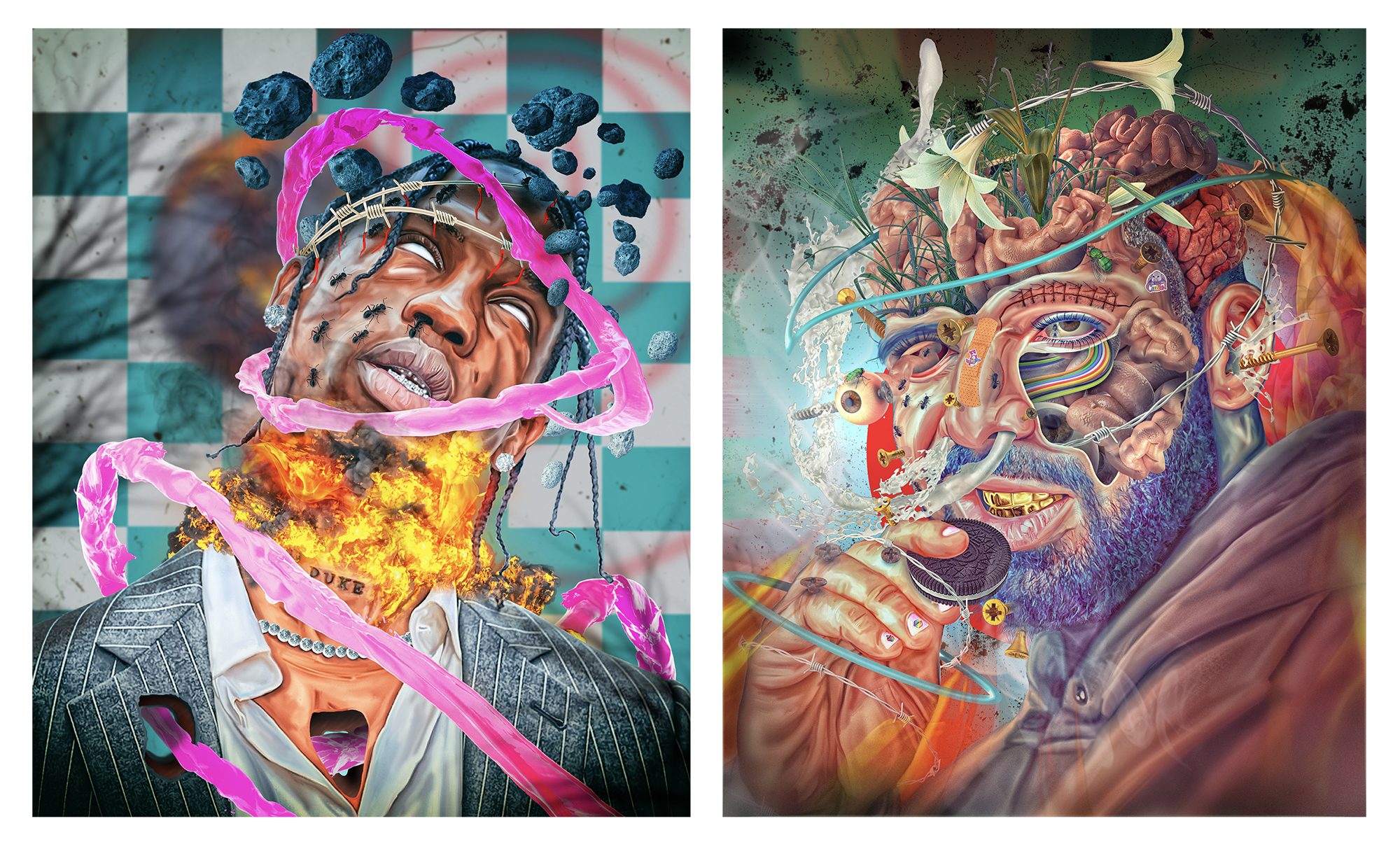

Other works, like Sicko Mode, are much more intensely illustrated. This portrait starts with an original image of Travis Scott and overlays creeping insects, swirling pink fluid and flames while cutting away portions of the famous rapper’s body.

However, the images that Gastinell posts on his website don’t often match the finished products you’ll see hanging in galleries and shows. His main method is wood printing, which, as he will tell you, often leads to mistakes. Yet whereas “perfectionist artists,” as he puts it, would see these printing errors as a problem, Gastinell sees it as a creative opportunity. Simultaneously “crossing out” mistakes and drawing new figures onto the already highly dense work, Gastinell creates richly decorated and yet highly affordable small-form pieces.

In the end, this theme of accessibility and endless reproducibility is something that Gastinell emphasized in our interview with him. Repetition with small differences—the driving force behind the mid-century boom in pop art—is something Gastinell seems to have mastered.

Brandon Gastinell | Photo by Sarah Elliot

So I heard you once tagged [Sacramento artist’s] David Garibaldi’s studio. Tell me about that?

[Laughs] So I was with my friend, and I had gotten a rejection email for the 50-billionth time from a gallery. I was trying to get my work seen in the area … Me and my friend were out doing street art, and we were looking at David’s building, and I was like screw it, I’m probably gonna get in trouble for this, there are cameras right there. I was just really frustrated because I felt like a lot of the people who were in charge of the art scene at the time were only letting their friends and people who they considered cool in. It wasn’t out of spite, though. The whole point of street art is to get seen. The next morning I wake up and I get a tag on Instagram. David has a recording like, “Who did this to my building? I want them to do a show here!” At first I was thinking it was, like, a setup and the cops would be there waiting. But in the end, he was like, “I really like your work!” My first show was there with David. He helped me out. I wouldn’t do it again, though.

Did anything come of the show?

Well, we sold only like one piece out of 30. So I was like, either nobody in Sacramento is buying art, or there’s something I gotta tweak. Then, I noticed that the ones that really sell well are the 8x10s on wood. Now, I think of selling art as like selling streetwear clothing. Like a small thing for $65—maybe a college kid can afford it. I see a lot of artists that make their stuff high priced. That’s understandable, but for me, that’s the best feeling, making affordable art. I would honestly say that my style changed a lot from that.

Left: Sicko Mode | Right: Drake Eat Oreo In Hell

Warhol features a lot in your art. How did you first get into Warhol and what kind of inspiration do you draw from?

So when I was about 18, when I first started photoshopping, the first photos that I ever stumbled upon were the [Warhol] Polaroids of Debbie Harry. It’s interesting, because I’d seen the soupcans before, but before that I had no idea who the artist was and what pop art was. What really drew me to Andy’s work was how big of an artist he was … how he was able to transform art and not necessarily create pop art but take it to the mainstream. Throughout his career he was shut out from the art community. When I first started making art, it felt like a closed group to me.

One of your shows was titled The New Pop Art. Do you see yourself as a pop artist in the same vein as Warhol and the like?

I think [my art] is trying to find a new spin on pop art, because we have so many more tools than what artists had. We have Photoshop, we have 3D art, etc. My work might not be the brightest, or saturated with colors like other pop art. I want to reinvent pop art—not in an egotistical way—but renovating something. I don’t see a lot of pop art made with tools we have currently. I want to renovate and take my time with it.

I Feel Like Warhol exhibit | Photo by Sarah Elliot

What are these processes that you feel are underutilized?

I think people don’t want to take the time to learn something. They don’t wanna take the time to learn a new program… Some artists who are really good painters are stuck in, “I want to paint and I want to chastise everything else that is done with a computer.” When I first started, an artist just right at a booth next to me [at a show] said to his friend, “If you make it on a computer, it’s not real art.”

You incorporate a lot of surrealist and maximalist elements into your work. How would you characterize your portrait style?

At first I would have said, I like that word, maximalist! Now I’m trying to take things away, because sometimes simplicity looks good. At first, I really did try to characterize my work as pop art, but I honestly never felt that. I guess right now I’d say it’s mixed media. I really don’t know—it sounds stupid, but I prefer people to say to me: “This is what it is.”

I’m not trying to make the image better, but enhance it. I want to transform something and make it my own in a way. For example, I’ll want to take an image of Kanye West and make it how I envision it. There’s always more you can do to an image.

Left: Handle With Care | Right: Jean Michel Basquiat 1982

What mediums are you inspired by?

Mainly prints, painting and digital collages. When you transfer digital art onto a canvas, it can kind of look a little wonky. It’s very expensive to experiment on canvas with digital art. Not a lot of digital artists are perfectionists, but they want their images to be crisp and clean. So what happened with me is, I was doing these images and figuring out how to get them onto the wood, and there would always be glaring mistakes, so I used to “X” those things out, and I thought “That looks kind of cool!” It’s really hard to be perfect with what I’m doing.

So you often do a series of prints, and then make them different with these additions?

They’re all original but they look different. [During a show in Oakland] I had two Billy Murray images with two different paint patterns. I sold the one she wanted and [she] got upset. Her friend said “What’s the difference?” and she responded, “No, can’t you tell the difference between the paints and patterns?” Those are the differences. Sometimes subtle, sometimes not so subtle.

Brandon Gastinell | Photomaximo

Brandon Gastinell’s new exhibit I Feel Like Warhol is up now at the WAL Public Market Gallery (1104 R St., Sacramento). You can check out some of Gastinell’s pieces on the gallery’s Instagram page (@walpublicmarketgallery), but for best results, go see it in person. The exhibit stays up until June 4, 2019. You can learn more about Gastinell at Brandongastinell.com.

**This piece first appeared in print on pages 18 – 19 of issue #292 (May 22 – June 5, 2019)**

Comments