Annie Owens-Seifert and Daniel “Attaboy” Seifert. Photograph by Nicholas Wray

Annie Owens-Seifert and Daniel “Attaboy” Seifert. Photograph by Nicholas Wray

Turn the Page: The First 10 Years of Hi-Fructose is likely one of the best contemporary art exhibits the Crocker Art Museum has ever displayed. It’s evocative, delightful and sometimes surprising.

But mostly, it’s accessible, which was a goal for both its curators at the Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art, and for Hi-Fructose magazine founders and editors in chief, Annie Owens-Seifert and Daniel “Attaboy” Seifert.

Accessibility to contemporary art has been part of the mission for Annie and Attaboy, who started self-publishing and sustaining Hi-Fructose 10 years ago. They brought what some considered “lowbrow” art to the mainstream and onto magazine shelves, affirming that this form of expression by living, local artists deserves just as much attention as “the greats” hanging in the homes of the elite and on loan to museums.

Turn the Page takes this mission one step further, by bringing the art from the magazine pages to the people.

“For a long time, I found many modern museum showings to be ‘one note’ compositions or presented as a wealthy family showing off their [investments] collection,” says Attaboy. “Honestly, I often enjoy many of the gift shops more. All the artists shown in Turn the Page are living, working artists and complement each other. They aren’t afraid to tell a story, or show you what their interests are.”

Those stories can range from political to personal—the struggles and triumphs of life experiences, emotions of family and children, divorce, assault, natural disasters and the impact of war on humanity.

Mark Ryden, The Meat Train (No. 23), 2000. Oil on canvas, 17 x 23 in. Private Collection. © Mark Ryden.

Pieces from Marion Peck, Mark Ryden, James Jean, Yoshitomo Nara and 47 other renowned contemporary artists from across the world who have been featured in the pages of Hi-Fructose over the last 10 years were carefully chosen to expose a broad audience to artists who use their media as tools to visualize what is happening in contemporary society.

“The pieces are all so different but I think the one characteristic shared throughout the show is accessibility,” says Annie. “And I mean accessible in terms of connecting with the viewer. Art can be thoughtful, intelligent and provocative and still not require a master’s degree in order to discuss or understand it in the way a lot of high concept work does—that to me is exclusionary. This work is with the viewer, not above them.”

Jean-Pierre Roy, The Incunabulist, 2015. Oil on linen, 50 x 38 in. Courtesy of The Grauslund Collection.

The entrance into the exhibit is a clear indication of this. Both the entrance from the staircase and from the elevators open up into an immersive two-room installation by American artist Mark Dean Veca that splashes across nearly every inch of white space.

Veca fabricates these temporary, spatial pieces first in vinyl, then goes back in and hand paints improvised line work, reflecting his parents’ jazz musician background. The resulting impact is loud, meaningful and mesmerizing; a perfect entrance to the rest of the exhibit.

Turn the corner, for example, and visitors are greeted by Shepard Fairey’s Rise Above. Fairey has been creating his politically charged movement art for more than a decade. His latest work has been displayed on skyscrapers from Las Vegas to Sydney, Australia to Berlin, Germany. The immediate gratification of seeing one of his pieces live in Sacramento right after the Amplifier Foundation’s “We the People” campaign against the Trump inauguration leaves an impression.

The globalized element of the exhibit, especially in terms of shared social issues, stands out throughout the exhibit. Walking toward the sculpture Black Hoody by Erwin Wurm of Austria, one can assume in America what the sculpture of a youngish, short, dark, hooded figure could mean.

The artist’s actual description—that the statue is a British soccer hooligan—is surprising at first but does lead to a deeper conversation of our perceived notions and our stereotypes, and how they compare to stereotypes in other cultures.

For Annie, Marion Peck’s work stands out as a favorite. The exhibit includes a cute, and on closer inspection, chuckle-worthy, Peck painting of rabbits having sex in a forest.

“Her work is elegant and graceful yet not pretentious,” Annie says. “The sense of humor and intelligent anarchy in her work is an element that permeated the underground art world back when I first became aware of it. I’m happy to be seeing it now, her underlying attitude unchanged, in a museum where people bring their children. This of course is not the first time her work has been shown in a museum but that it’s part of the Hi-Fructose show makes me very happy.”

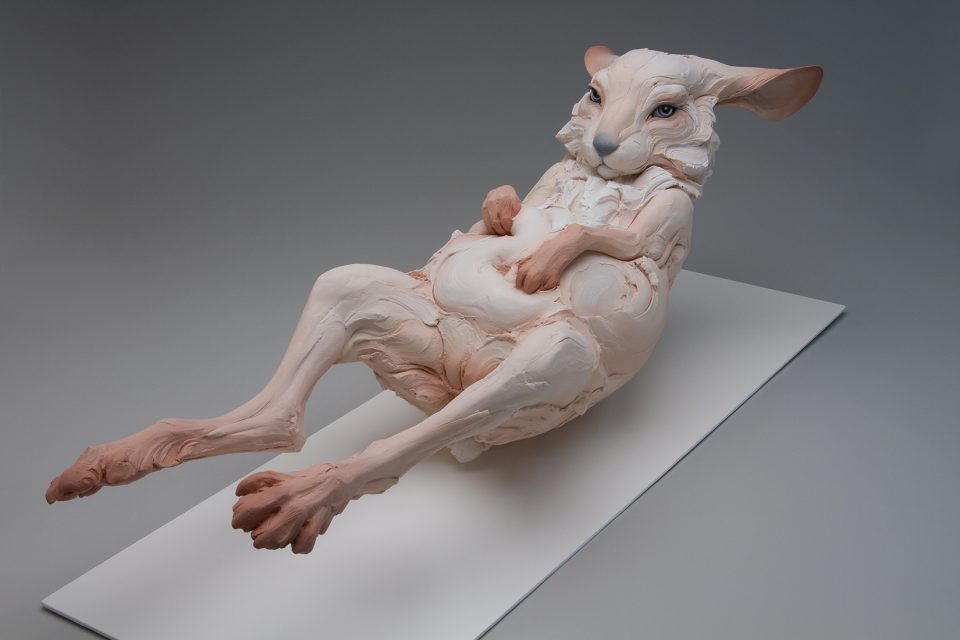

Annie and Attaboy both must share a rabbit fetish, because Attaboy’s favorite piece, by Beth Cavener, also showcases the animal in an exposed way.

Beth Cavener, Unrequited (Variation in Pink), 2015. Resin infused refractory material, paint, 14.5 x 15 x. 43 in. Courtesy of the Artist and Corey Helford Gallery, Los Angeles, CA.

“Her sculptures are dynamic, fluid and have a narrative that shines through,” Attaboy says. “I like that people’s first response is ‘Oh, bunny!’ then a few moments later, the theme of the same work has a way of creeping up the spine as the viewer anthropomorphizes the art with the weight of their own baggage.”

Individual pieces were picked based on a number of factors, including art piece availability, logistics and visual and narrative balance, Annie says, not on who was “best” or “most deserving.” As for location, the cities of Sacramento, Akron and Virginia City are the only ones to see the exhibit, for which the editors are grateful.

“Why should big cities have all the fun?” Attaboy says. Annie notes that a bigger audience was reached as well, as opposed to if they had shown in larger cities.

“Still can’t believe the thing came together and is real,” Attaboy adds. “I’m amazed to see children and older folks stare and enjoy and investigate the art. That took me by surprise. It’s been weird for us to see this thing realized. The Virginia MOCA did a great job doing all the leg work, but it wasn’t easy to select only 51 artists. But it became its own great thing. Kinda like a movie based on a book. I’m pretty sure there will be a more straight-up gallery show in the future.”

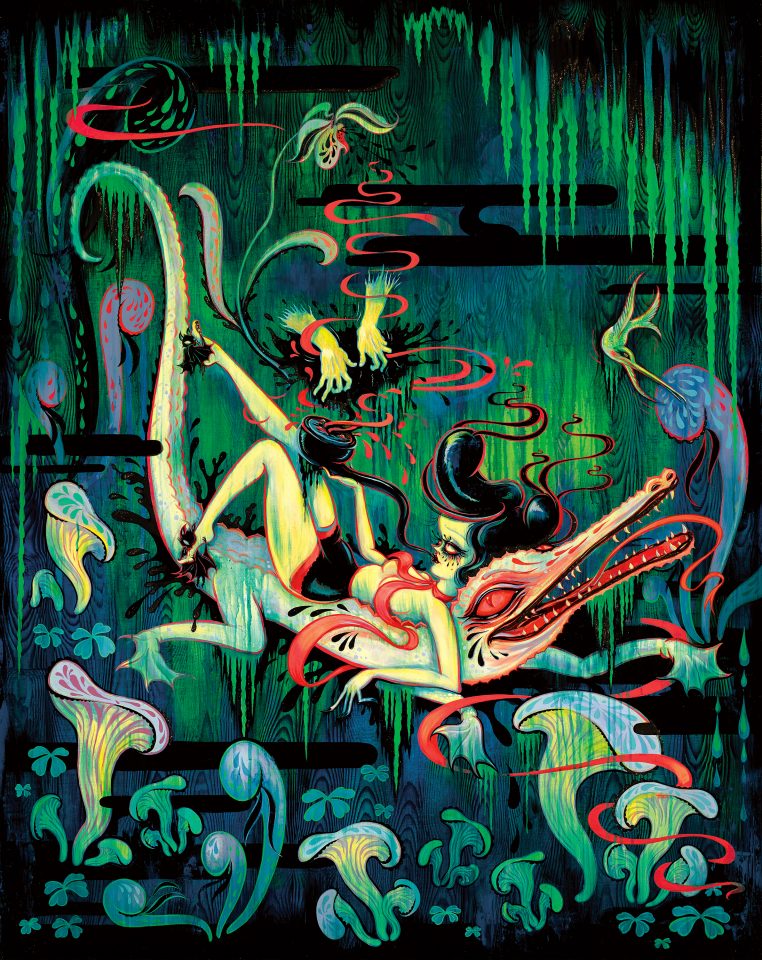

Camille Rose Garcia, The Ghost of G Sharp Seven, 2013. Acrylic and glitter on wood panel, 60 x 48 in. Courtesy of the Artist and Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. Photograph by Karl Puchlik.

© Camille Rose Garcia.

Annie notes that this is too diverse of a show to throw any kind of blanket statement on it, but she makes one thing clear: each artist in the show had begun cultivating their own career long before social media was a thing.

Jennybird Alcantara, Creatures of Saintly Disguise, 2012. Oil on wood, 65 x 48 in. Courtesy of AFA Gallery. © Jennybird Alcantara, All Rights Reserved.

“In the ‘90s and early 2000s before we began publishing Hi-Fructose, Daniel and I as artists had been milling around an already vibrant art scene humming below the radar before we started publishing … An arena that was not dependent on social media,” she says. “Many of the artists in the show had made names for themselves before we came along. We were just covering what wasn’t getting coverage at the time and there was so much. That was our job. Years later, social media exploded and helped to push this art scene out above the glass ceiling, but it didn’t make these artists.”

Many of these artists, she says, showed in galleries that didn’t follow the status quo, worked as illustrators, published indie zines, did poster art, made comic books, band art and street art that was actually on the street (sans PR reps).

“We’re fortunate that each one of them said yes when we asked if we could do a feature on them,” she says. “If not for artists that keep pushing boundaries there wouldn’t be a reason for us to keep going.”

J Fosik, The Abyss Stares Back, 2011. Wood, paint and nails, 39 x 27 x 14 in. Collection of Ken and Lauren Golden. Photograph by Nicholas Wray.

Turn the Page: The First 10 Years of Hi-Fructose will be on display from June 11–Sept. 17 at the Crocker Art Museum, located at 216 O St. in Sacramento. The Museum is open Tuesday–Sunday from 10 a.m.–5 p.m. (open till 9 p.m. on Thursdays) with general admission $10 for adults, $8 for seniors/military/college students, $5 for kids 7–18 and free for kids under 7 and members.

**This article first appeared in print on pages 18 – 20 of issue #243 (July 3 – 17, 2017)**

Comments