Artist Mark Bryan believes the Rupture is at hand

Believe it or not, another world exists. It is one in which white collar rabbits scheme around bonfires with rifles, a monolithic statue of Jesus soars through the sky discharging bombs from his chest cavity, babies beat on each other in a boxing ring and Sarah Palin is suddenly transplanted to a tea party at the beach with Alice, the Mad Hatter and company. One second Bambi is standing by the river, the next second he will be zapped by an alien spaceship.

This foreign world exists in two dimensions instead of three. It is a world that is sinister, surreal, chaotic, mysterious and beautiful at the same time. It is conceptualized in the psyche of Los Angeles native Mark Bryan, trickling from paintbrushes onto canvases where it then comes to life.

A glimpse of this world can be found at the James Kaneko Gallery at American River College, where Bryan’s paintings are on display in the exhibition The Rupture, not to be confused with the Rapture.

Upon entry into the gallery is Bryan’s artist statement, excerpts from writings of The Church of the SubGenius explaining how the Rupture works: one moment you are seated at the table eating breakfast with your spouse, the next you are leaving your spouse behind as you are swept away on the vehicle of the sex goddess.

Not unlike something that would occur in a Bryan painting. Like his own work, The Church of The SubGenius uses a sense of humor that plays upon human absurdity.

And absurdity is something Bryan has stood witness to since he was a kid, growing up during a time when any day could have been his last, erased by nuclear war. That’s what society was telling him, anyway. This may be why a number of his paintings depict what he refers to as “impending doom.”

“I think everybody, depending on the generation they grew up in, is soaked in different influences,” he says.

Bryan had been drawn to surrealism since he was a kid, and for a long time he was stuck on Salvador Dali, he remembers.

MAD Magazine, science fiction, superhero comics and the lowbrow art featured in ZAP Comix all also played a role in shaping his artistic palate as a youth.

During the ‘60s, Bryan’s attention was also inadvertently shifting to politics, partly because of the Vietnam War and the draft, he remembers.

“When you actually can be sent somewhere to kill people or be killed, that sort of ups your political awareness rather quickly,” he says.

Bryan found inspiration in political Chicano art, too. It was bound to happen in Mexico City, where he had spent some time, surrounded by political murals by artists like Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. The two Chicano artists he lived with during art school in Los Angeles were influential on him as well, one of whom he helped paint a 40-by-60-foot mural for César Chávez in Tehachapi in the ‘70s, which would be hung behind Chavez at the United Farm Workers convention.

Some of Bryan’s own most recent political commentaries have been in the form of the sardonic Mad Tea Party series, of which the first painting he credits with launching his career as a full-time painter.

That painting was inspired by the Bush era, a time when Bryan remembers being really disturbed and unhappy with how right-wing politicians were handling things.

“I was trying to depict my feelings about it, and I thought the Mad Tea Party would be a great setting for them, because all the characters seemed so crazy,” he explains.

Little did he realize the extent that the painting would boost his popularity as an artist, or that several years down the road a Tea Party movement would emerge and that the right wing would embrace it.

At that point, there was no question that there would be a sequel to the original Mad Tea Party piece.

Bryan saw no shortage to the madness: BP had just dumped gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, and Sarah Palin had essentially duped the Tea Party into making her their queen.

Thus, The Mad Tea Party Part D’uh was born, this time set against the beach. BP oil seeps into the ocean blue while Palin, dressed in Queen of Hearts garb, sits in the company of Rush Limbaugh reincarnated as the Mad Hatter and other right extremists, smirking devilishly while pouring Kool-Aid into teacups.

While he guesses that around a quarter of his work is political, Bryan says that he is not a political junkie. His paintings are more like outlets for comments he wants to make on human nature, whether or not they involve war, religion, left versus right or propaganda.

“I think an artist should be a person who reflects their feelings about the times and their own personal experiences, and so this is my particular take on what is going on in this world,” he says. “If I paint a landscape or something I usually have to put something else in it to make a comment, usually something disturbing,” he says.

Quite a few of his pieces peg religious fundamentalism, he says, because it’s an easy target.

“People in every moment in history think [the end of the world] is going to happen really soon, because everything is always so screwed up,” he says.

“In my lifetime I probably remember five or six of these guys saying the world is going to end.”

Some inches further along the wall at the James Kaneko Gallery hangs an oil painting of a round-faced, beady-eyed man in a suit and tie. Capping the crown of his head is an automobile from which a crazed lucha libre rabbit is steering the wheel of his brain.

This piece, El Conejo in His Head, is one of a series of what Bryan calls his psychological portraits.

He offers a simple explanation: “Sometimes people behave in ways they don’t want to.”

Other pieces are parodies. For instance, Bryan’s Pushing Clocks depicts Salvador Dali against a barren landscape similar to that in Persistence of Memory, wheel-barrowing around a pile of his trademark melting clocks whilst dressed in a bunny suit.

This, Bryan says, was an easy way to drag Dali into the lowbrow, pop surrealism world.

Sometimes a painting is preceded with one to two sketches. At other times, paintings come a bit more spontaneously.

“I still start with an idea, like I’ll think I want to paint ballerinas and a landscape, but I have no idea what it’s going to look like,” he says. “It’s kind of a dreamlike process, they change a lot as I’m painting and a sort of picture or vision starts to crystallize slowly.”

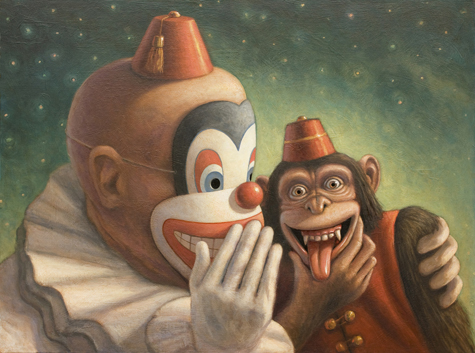

Monkeys, rabbits and robots are some of Bryan’s go-tos used to incorporate humor into a piece, simply because he finds them inherently funny. Babies are another.

“Babies, you know, they are kind of creepy and I don’t know why I keep painting them,” he says. “And I put them in weird situations you never see them in, smoking cigarettes or boxing, stuff like that. Visually they’re fun to play with.”

For instance, another one of his parodies is Maja con Conejos, based on the painting La Maja Desnuda by a painter he adores, Francisco de Goya. Like Goya’s piece, Bryan’s is also of a shapely woman leisurely positioned on her side, except her head is replaced with that of a rabbit, and she is surrounded by a hoard of babies with rabbit heads.

If there is an underlying meaning to that painting, it is this: “The Maja, with all of her 25 babies or whatever, is to me like a cautionary tale to young men, like, ‘OK, sexual attraction, this is what it’s really all about. So, watch out,’” says Bryan.

Politics or parody, a touch of humor is most always to be expected in a Bryan piece.

“I use humor to make it palatable and seduce the viewer into actually looking at a picture,” he says. “I think humor gives you a little reward for looking at a piece, like satirical humor especially, it’s a way of getting the point across without turning off the viewer, or making it more appealing.”

Robots, the Washington Mall being taken over by armies while humans become sheep (as seen in The Republic of Suicide), the cynicism was all too familiar. It felt something like a Vonnegut piece.

When Submerge asked Bryan whether or not he was a Vonnegut fan, he responded, “Yeah. I love that guy.”

Mark Bryan’s artwork is now being shown in The Rupture, an exhibit with Tony Natsoulus, at American River College’s James Kaneko Gallery. The exhibit will show now through Dec. 6, 2011. For more info on the exhibit, call (916) 484-8399. If you’d like to learn more about Mark Bryan, go to Artofmarkbryan.com.

Comments