The Invented Worlds of John Tarahteeff

“Most kids draw, but I just kept doing it,” says artist and East Sacramento resident John Tarahteeff of his early forays into art. Tarahteeff has been “just barely” supporting himself as an artist for the past 10 years; however, when he was in college, he decided to channel his creativity toward more practical pursuits. Tarahteeff graduated from U.C. Davis, majoring in landscape architecture and minoring in fine art, in 1994. However, he says that it wasn’t until his life after college that he did most of his studying of painting.

“When I graduated from Davis, I lived with my parents for a couple of years, so that was low rent,” Tarahteeff says. “In school, I was caught up with the landscape architecture studio courses, so I didn’t have much time to do my art stuff. When I graduated, I would just paint all day for like 14 hours a day”¦ After two or three years of doing that, I started to show my work.”

Back then his art did not bear the surrealist bent it does now. Tarahteeff says he experimented with a lot of different ways of painting before settling on the style for which he’s become known.

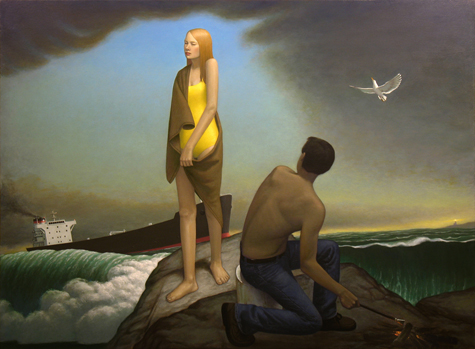

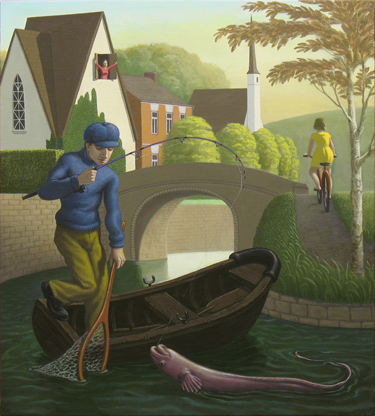

“There was a whole year there that I wasn’t even painting representationally,” he explains. “I’ve experimented with a lot of different ways to paint and settled into this sort of surreal representation, I guess that’s the best way to put it. And it’s sort of developed, but once I hit on that, I used figures and landscapes and invented worlds, I’ve just kept working in that vein.”

Tarahteeff’s latest collection of works Seaworthy can be seen now through Oct. 3 at the Solomon Dubnick Gallery. In the following interview, Tarahteeff shares his thoughts on interpreting his own work, his feelings about the use of the term “surrealism” to describe it and also sheds some light on his artistic process.

Do you consider yourself a surrealist painter?

I don’t really like that term too much, but I’m not really fighting it anymore. It kind of gets people in the ballpark if I say “surrealism”—the idea of the consciousness coming through. Anyone’s a surrealist anytime they do something. It’s descriptive, but it’s not real descriptive.

Are you a fan of the surrealists?

Yeah, I remember in high school, when [I saw] De Chirico, and his surreal, empty landscapes with the long shadows, I was really struck by that. Even though in humanities, I’d studied more realistic painting, I was like, “Wow, I still like this. It’s kind of abstracted.” I think that was an evolution for me. I think most young people tend to like Rembrandt, like, “Wow, it looks so real.” That was the first time I think that I really liked something not for the virtuosity of the painting, but just because of the mood.

Before you said you tried a lot of different styles. How did you settle on what you’re doing now?

I’d noticed that when I was studying, I was trying to figure out what the essence of painting was for me, like what was important in terms of form. I’ve always had a formal bent to my work—just line, texture, color, tone. What is really important to me? Content, it’s like, what’s important narrative to one person is gibberish to another. So what about form? Maybe there’s a universal thing that’s the essence of what I want to say formally? And so I explored minimalism and abstraction, and representation dropped out. I was trying to get at what can I take away and it’s still a painting to me”¦ I came to the conclusion that I was stripping away everything, and it was almost like I was in my own world and I turned the volume down so low that I could hear what was going on, but it wasn’t communicating to anyone else”¦ So then I just flipped and went in the opposite direction. It was like, take on everything. At first it seemed weird taking on representation—like cartoon-y and everything seemed cliché, but I thought, “Just do it anyway.” And then, as I did it, I found that I really liked it, just coming out of that low volume and all of a sudden incorporating everything that painting could do. Now I tend to gravitate toward paintings that try to do everything, like old master paintings where there’s narrative and abstract qualities in terms of the colors and the composition—just all these levels and symbolism.

A lot of the paintings of yours I saw don’t seem to have much empty space. They’re almost sensory overload.

In some of them, yeah. It’s real dense. There’s something about when the images get dense, there’s an inevitability about them. You can’t really move something without messing something else up. It’s like the painting has to be that way, because everything is so intertwined and interdependent that formally it has a resolution.

In the description of your Picturemaking series that you wrote for the Dubnick Web site, you said that you don’t start a piece of work around a particular theme. If you don’t paint with a theme in mind, where do you begin?

When you called me, I was sketching. I sketch all the time. I’m sketching every day, even if I’m going to paint that day. Usually what I’m drawing is figures in different positions, almost like what a comic artist would draw. After a while, like when I go and revisit the sketches, I go, “Oh, this figure would fit in here.” At first, it’s just fitting these figures together in a sort of puzzle”¦ The process is just making an image for its own sake, and some world emerges. I’ll put the sketches away, and sometimes I’ll see a sketch that I put away maybe two years ago, and I’ll start adding to it again. Eventually, I’ll have something that I’ll try on a canvas. A lot of times, it doesn’t work out at first, and I take something out even on the canvas. Even when I get on to the actual painting, a lot still changes.

Is that difficult to change the composition once you’ve started painting?

Sometimes it goes pretty straight, but most of the time it doesn’t. There are times when I think I’ve got a totally resolved composition, and I go to the canvas and work for a month on it and realize it just isn’t going to work. I’ll save one figure or something that I really like and then just try to rework something else. Sometimes the ghosts of the other figures, like when I’m painting them out, they start to become something else. You start to see other images within it and a whole new painting can come about.

And you’re doing all that without the benefit of Photoshop.

Yeah [laughs]. Just about two years ago, I got turned on to the whole computer thing”¦ I don’t compose with it, but the one way it’s been helpful is that if I think of something like, “Oh what are they wearing,” or, “What instrument are they playing,” and I don’t really know the details, I can go online and just look up “bagpipe,” and I get little bits of information that are real specific that aren’t quite in my memory bank, and it fleshes out the details.

Musical instruments seem to pop up in your work often. Do you play music yourself?

Yeah, I’m in the closet guitarist vein. The only ones who really hear it are my girlfriend and me. And my girlfriend’s a cellist, so I’m learning more about the classical music. I’ve always been more into pop music. But that’s something I’ve noticed, too. Instruments are coming in there more, and I’m not sure what that’s about.

When you look back at older paintings that you’ve done—maybe 10 years ago—do you pick up the symbolism more now than you did when you painted it?

That’s what tends to happen. A lot of times, I can’t even title a piece when it’s done. I have the hardest time, because I need that distance to see what it’s about. I just see all the formal components when it’s more recent. When it’s been done for a while, I just take it on its own terms. I don’t think of it as red over here, or black over there. I just look at as if someone else did it, like, “What does that mean?” I do that with other artists’ works already. I start generating a narrative, even if it’s not what the artist intended, a story inevitably emerges.

For your latest collection at the Dubnick Gallery, is there a narrative in those paintings?

Yeah, I think a lot of times, independently a painting might have a narrative, but what intrigues me is the narrative over the course of my work. That’s the one I’m more interested in”¦ I see characters that recur in my paintings. There are things in my paintings, like a bird”¦and I’ll see that bird in a piece three years later. I know these archetypes in my head have some sort of meaning, and I’m bringing them into each painting. Those archetypes are what I’m interested in, at least as far as narrative. I don’t think in one piece that I ever really get at the narrative that I’m after, but it allows for these archetypes to inhabit these prefabricated worlds. A lot of the genres I take are already out there as far as art history goes. They’re scenes that exist already, and I’m kind of mutating them.

One painting in particular of the new series that I wanted to ask about was The Game; it seemed almost nightmarish. I was wondering what the thought was behind that one.

You know, I don’t know. That one just kind of came out. I’m not sure [laughs]. Yeah, but there’s something. I know that in a lot of my older paintings, I play with the game of desire and seduction. I think it has something to do with that, but I don’t know specifically.

Comments