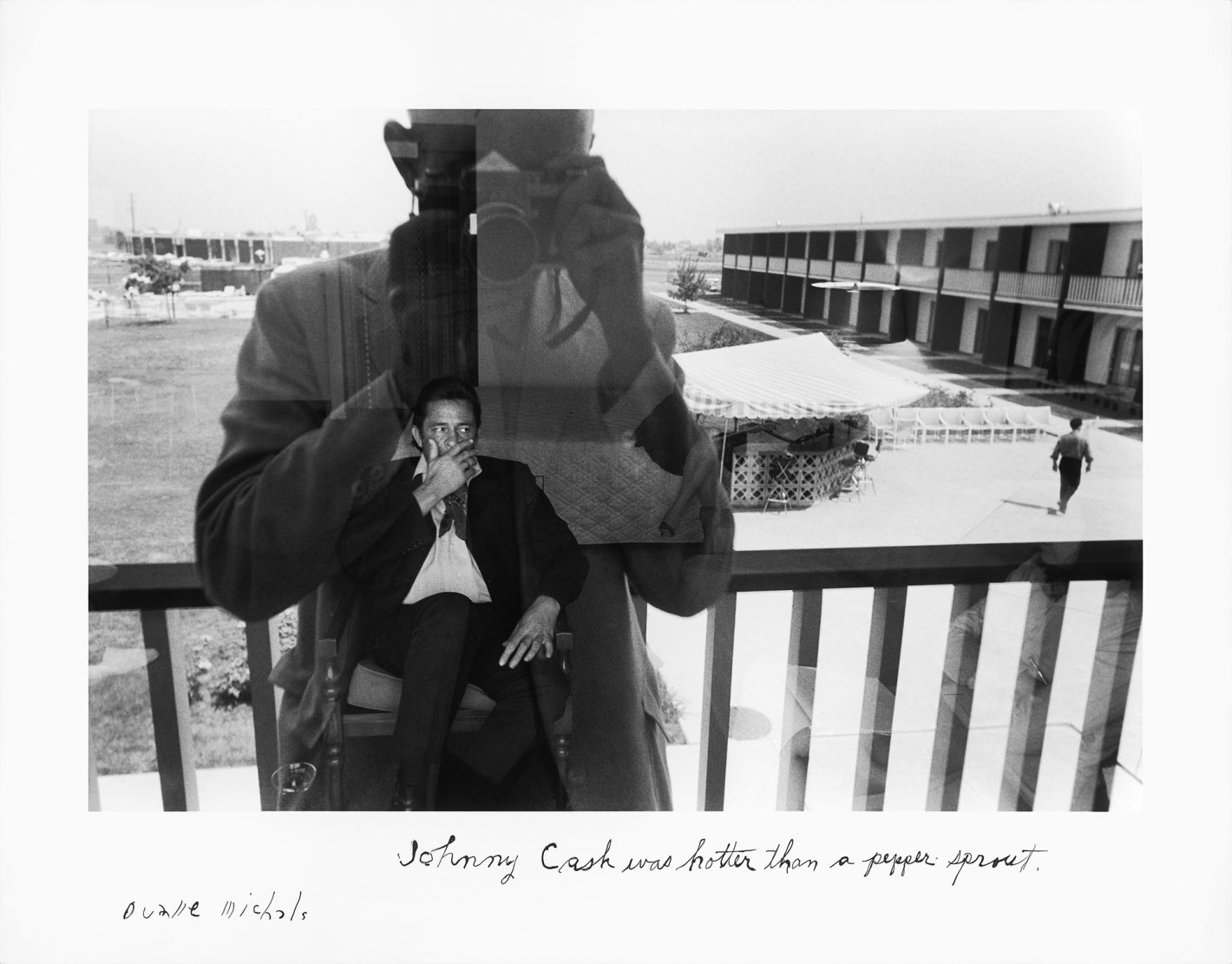

Duane Michals, Johnny Cash, c. 1970s. Gelatin silver print with hand-applied text, edition 2/5, 6 5/8 x 9 15/16 in. © 2018 Duane Michals / Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

Duane Michals, Johnny Cash, c. 1970s. Gelatin silver print with hand-applied text, edition 2/5, 6 5/8 x 9 15/16 in. © 2018 Duane Michals / Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

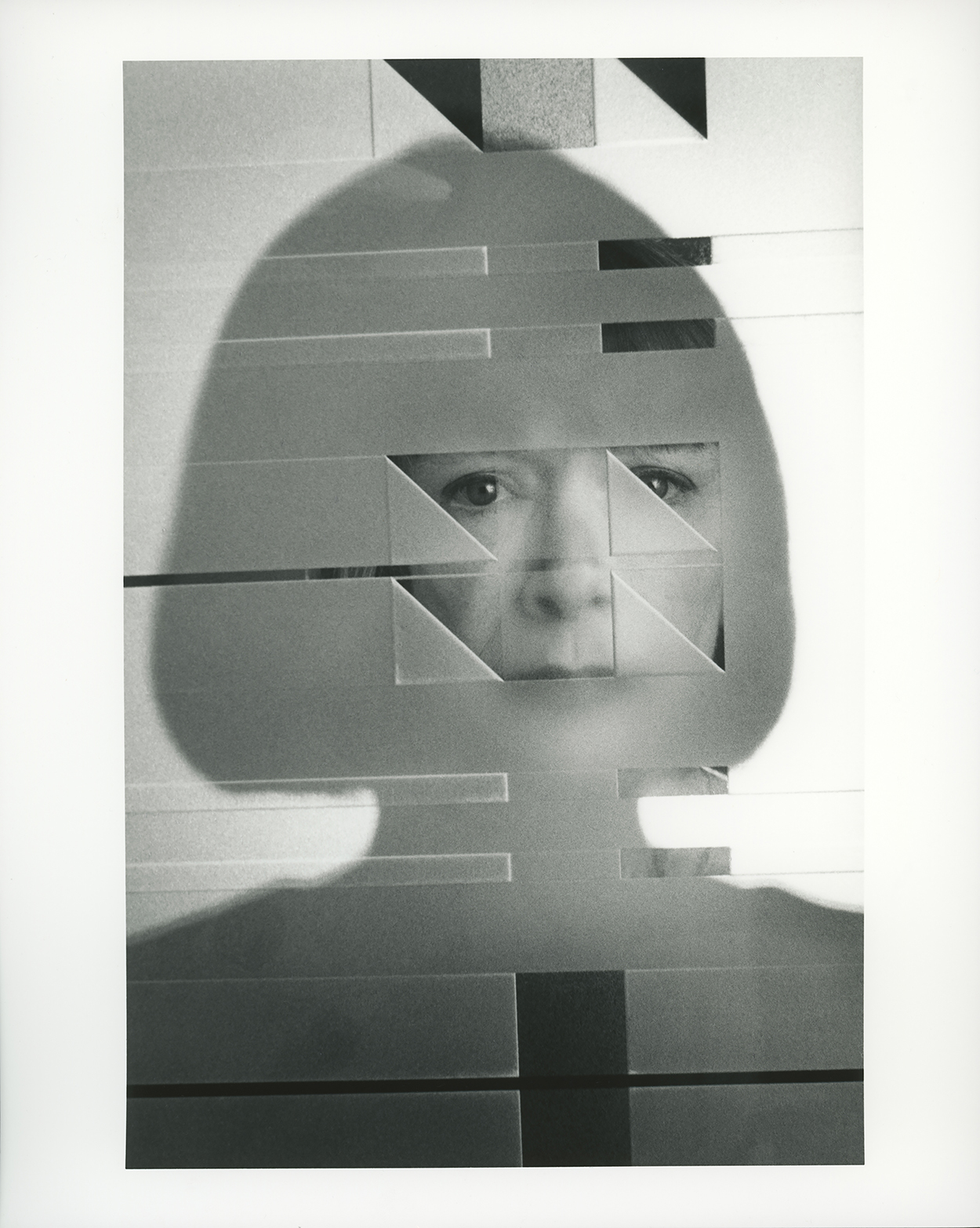

Duane Michals’ work is so incredibly full of life. There’s the playful portrait of Joan Didion, for one, looking through a smoked glass pattern on what must be an airport security door in such a way that it seems her eyes are playing peek-a-boo with the rest of her face. There is also the portrait of Johnny Cash, slouched solemn-like in a chair, with Michals’ own reflection, camera in hand, superimposed, blocking out the light from outside of what must be a glass door. Michals’ work is incredibly complex in its simplicity; creep-master Stephen King behind a spider web, ever-androgynous Tilda Swinton admiring her reflection as she’d dressed—backward, as a 19th-century English gentleman. Michals is always at play and doesn’t take himself seriously, but what he lacks in pretense, he makes up for in passion.

“Whoever said a picture is worth a thousand words is the biggest bullshitter ever,” Michals said. “A picture is such a small part of it.”

He often takes the time to write on his photos, to, as he puts it, “enhance the story” with witty quips like, “Johnny Cash was hotter than a pepper sprout,” or opaquely poetic musings like, “In Germany I named my tank ‘c’est si bon’” on a portrait of Eartha Kitt.

I didn’t know Michals before this interview, but his is the name I’ll say next time someone asks me what living person I’d most wanna invite for dinner. He’s jovial, funny as hell and he has stories about all of your favorite people—and at 86, he’s hung out with a lot of the people we never will, so in that way, wishing for Michals is like wishing for more wishes, and talking to him was a dream come true.

Portrait of Duane Michals by Raymond Adam | Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, NY

So how spontaneous are these photos? In talking to you, it seems like you’re kind of playing with the moment all the time.

It’s true, I am.

I read that you never had a studio, is that right?

I never did. I didn’t like studios. If you like milk, buy the cow. So we needed a studio, but I never wanted to be a business. I never wanted to have a staff of 10 and that stuff. I always saw myself as working on a small scale. I still do. I don’t see myself in any way being a big time, big shot.

Is it a way of just being humble?

No, it’s just the way I am. I guess I’m humblish … I just want to do the work and don’t owe anybody money and just have a lot of sex.

Those are great goals!

Yeah, and make the sex first on the list.

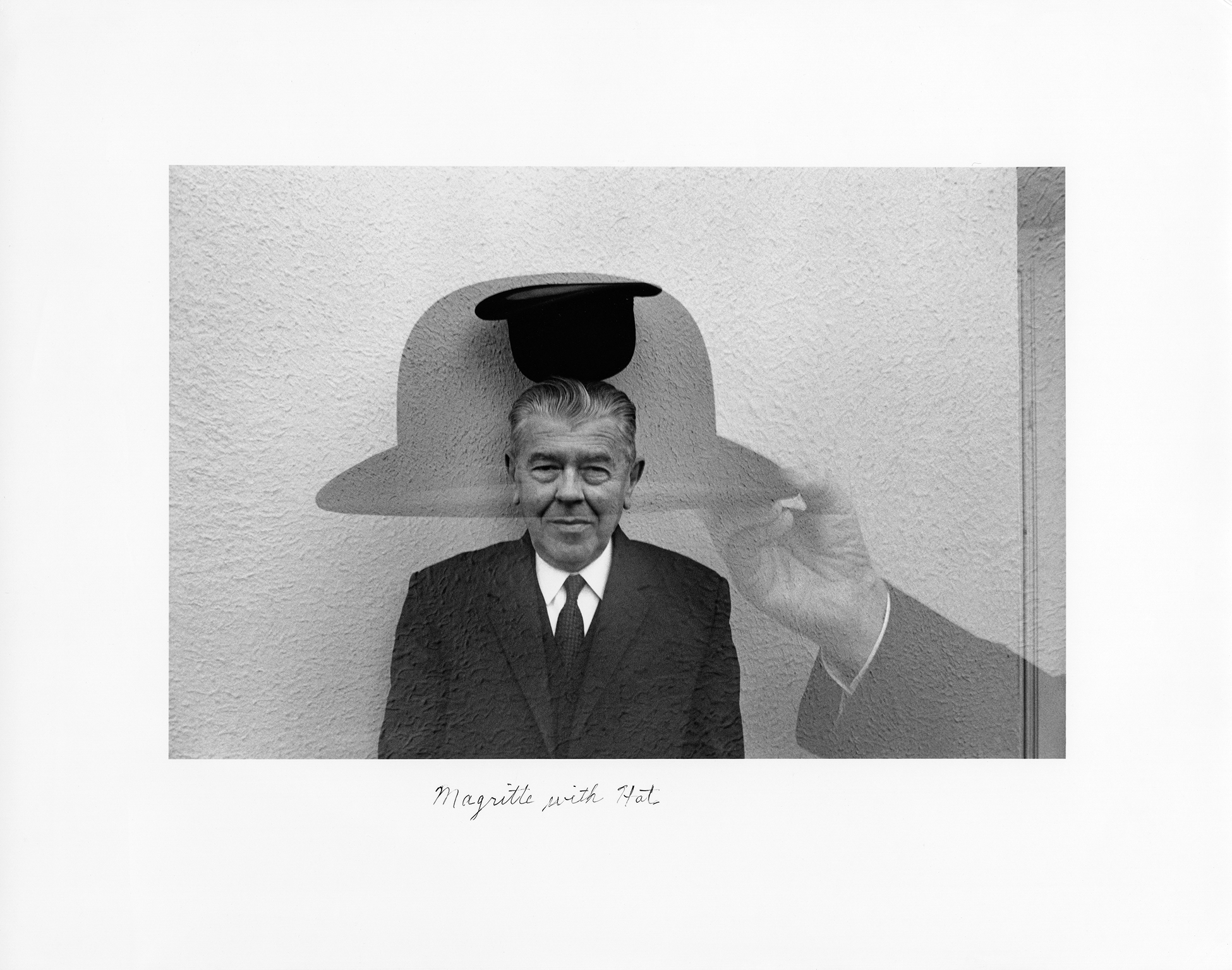

Duane Michals, Magritte with Hat, 1965.

Gelatin silver print with hand-applied text, edition 25/25, 6 3/4 x 10 in. © 2018 Duane Michals / Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

So I read that you’re completely self-taught. How could that be possible?

No, I went to Russia when I was 26 in 1958—don’t do the math! I borrowed a camera because I didn’t have one. I’d taken a little photography course once, but it didn’t amount to anything and I didn’t think of photography as a destination. So I borrowed a camera and figured it out. That’s why I’m so angry about photo schools. I gave a talk at the graduation of the New School, and I asked the kids what they spent—something like $200,000 on photography school? Are you nuts? Give me that! That trip was literally my photo education. You put the thing in the camera. Click the other thing, put the dial on 16 when you’re outside and you put the other thing on 500. That’s what I did. It’s so simple. The trip changed my life and my exposures were amazingly good!

But your work is so great. If it’s simple as that, what differentiates you—is it your taste?

First of all, I didn’t go to photo school so I didn’t learn the photo rules. When you go to school they have to teach you something, and the teachers teach you what they do and the rules and you learn to worship the photo gods. I never learned any of that, so I didn’t worship at the altar. One day, I just decided I was a photographer and that was it.

Duane Michals, Mr. Backwards Forwards (Tilda Swinton), 2016.

Digital chromogenic print with hand-applied text, edition 3/5, 5 x 7 1/2 in. © 2018 Duane Michals / Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

With Instagram, everybody kind of fancies themselves as a photographer. Do you see that changing photography at all?

Yeah and actually everybody is a photographer—it doesn’t mean they’re good. And listen, I love digital—fuck film! Digital is so great. It just makes taking pictures so much easier. I’m not interested in what something looks like, more like what it feels like. If I see an old lady crying, I want to know what her grief feels like.

Do you have to develop a relationship with these people before you photograph them?

Never! That’s the greatest bullshit I ever heard! It’s total nonsense.

Duane Michals, Meryl Streep, 1975.

Gelatin silver print with hand-applied text, edition 2/25, 5 x 7 1/4 in. © 2018 Duane Michals / Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

So then they reveal themselves to you as you take pictures?

No, nobody reveals themselves to me. Why would they reveal themselves to a stranger? No, that’s bullshit, too! It’s photo lore bullshit. It really is!

Then where’s the romance and playfulness come from? Your photos seem so intimate.

I don’t know, it comes from … I have a quotient of childishness, I think. I’m happiest if I’m saying something totally ridiculous! I can’t stand photographers who are serious. Essentially I’m just a big bullshitter, as you can see. But I never look down on jobs—any job. I did all kinds of jobs, you would be surprised. These celebrity portraits, travel photos, I’ve done Life Magazine covers, political campaigns, I did that album with the Police.

I saw that! Could you tell the story behind that album cover?

I know nothing about rock music. I was showing something, and I had an opening and this guy called—whoever the contact was—and he brought Sting to the opening. I never heard of Sting and he seemed nice and so they asked me to do the album cover. I didn’t know who they were, and as I was driving to meet them in the studio, I heard what I thought was the Police on the radio. So when I got there, Sting asked me if I knew their music, and I said I think I heard a song of theirs which sounded very nice. He asked which song it was and [I] started singing “Do You Really Wanna Hurt Me?” That was Boy George. He was nice and said, “No, we didn’t write that one.” That was very embarrassing, but we got along really well. It was one of my best assignments. I got paid a lot of money, they were nice and up for doing anything. It was great.

Duane Michals, Joan Didion, c. 1990s.

Gelatin silver print with hand-applied text, edition 1/5, 8 7/8 x 5 15/16 in. © 2018

Can you contrast this show at the Crocker with your first show—that was the Russia show, right?

Yeah, what happened was I came to New York when I was in the army. I was a second lieutenant in Germany. I did a book called The Lieutenant Who Loved His Platoon. It was about, well, it’s a long story, but being gay in the military wasn’t easy. Anyway, you should read it; it’s a good book! Anyway, I went to New York because I wanted to—I love books. You know, I only spend money on books and magazines. And so I didn’t know where to go and I had a degree from the University of Denver. I could teach art in Denver high school. When I got there [New York], I went to Parsons for a year and dropped out. It was a disaster, and I got a job working on a small dance magazine, $50 bucks a week—can you imagine that? I found out you could go to Russia at the time—and that’s at the height of the cold war. Nobody was talking to the Russians. No one was going there. So, it cost $1,000 to go on this trip, and I was making $50 a week, so $1,000 was a big deal. So I borrowed $500 from my mother and father and I saved up for six months, saved up $500, borrowed a camera from someone, and I said to my friends I’m going to Moscow. They said, “Fuck you, you’re not gonna go.” and I said, “No, fuck you,

I am going!” and the trip changed my life, because if I had never gone, you know, I never would have been a photographer.

Do you really think that?

No, I know it. I was never an amateur; I didn’t even have a camera, I didn’t take snapshots and when I got to Russia, they taught me to say something which I think means “May I take a picture?” and I just stopped these people and took pictures. I had no pretensions about being a photographer, but it’s all I’ve done ever since, and I may be dead any minute now, but I’ll keep going.

You timed it right. I’m recording this, in case you want your last words to be poetic.

I’m the last of the great Manhattan drinkers. My last words would have to be, “One more for the road, please!” I’m not a professional.

Duane Michals, Hell Grace Fool of Merry (Grace Coddington), 2016.

Gelatin silver print with hand-applied text, edition 3/5, 4 5/8 x 7 in.

© 2018 Duane Michals | Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

The beauty of that is that your photos speak louder than people who consider themselves professionals.

Yeah, well, I certainly know enough. I wasn’t a total fool, but you know, I was panicked when I couldn’t find my light. The light was the big deal, and I always would suffer over everything, especially back then, but even now. Not having a studio makes you dependent on a lot of other factors.

Can you tell me more about the portrait book?

Yeah, one of my favorite ones is the one of my mother. It’s a picture of my mother, sitting and looking out the window and the sunlight is coming in and you see a reflection. There’s moisture out there and it’s very still. I wrote a caption on it and it says, “Mother after father died.” And she’s sitting there and you only see her reflection and she looks very sad, and she looks like she’s tapping her fingers. Like she’s counting the time, watching time go by and to me, that’s the most profound out of the portraits because it suggests, and any good thing can only be suggested. You can’t put everything in there. You can reproduce someone’s lips or wrinkles or their nose, or whatever, but important things can only be hinted at. Grief is something that you can’t photograph. I can tell you what it looks like—tears tell you what grief looks like. Lighting or whatever, but these are all formal elements, they’re not grief.

Do you have anything important you want to say that I’m missing?

Not at all. You’re very nice. Thanks for talking to me for this long.

You’re a bad judge of character, sir. I’m rotten.

I didn’t mean it anyway.

Duane Michals’ exhibit, The Portraitist, is currently on view at the Crocker Art Museum (216 O St., Sacramento) through Jan. 6, 2019. For more info, go to Crockerart.org.

**This piece first appeared in print on pages 18 – 19 of issue #275 (Sept. 26 – Oct. 10, 2018)**

Comments