Whether or not the name Shepard Fairey automatically conjures images of pop culture subversion, punk rock idolatry or street-art politics is irrelevant at this point. The 48-year-old artist is responsible for some of the most iconic imagery to have ever befouled the sacred real estate of public spaces in the last 28 years—from the salad days naïveté of an “Andre the Giant Has a Posse” guerilla stickering campaign throughout the Northeastern United States in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, to an uncommissioned but extremely powerful presidential campaign poster for then-candidate Barack Obama with the simple message of “Hope” emblazoned beneath his image later on, Fairey’s work has possessed the kind of omnipresence that few artists in history have achieved. His has been a life inspired first by reclaiming public spaces with his artwork (rather than continuing to be inundated by corporate advertising), then marveling in the stoking of conversations raised by the imagery he’s introduced—a “vocabulary of motifs,” as he puts it, that at once are recognizably his, but which afterward have become the centerpoint of international protests, provocation, even lawsuits.

That Fairey has been arrested some 18 times for distributing his artwork is perhaps the greatest indicator of its power, though he admits that he relishes the benefits of no longer having to be quite so anonymous, or quite so secretive.

“I enjoyed the freedom of anonymity when I started, but I also didn’t enjoy the poverty,” Fairey explained to Submerge. “Having the opportunity to make art without worrying whether or not I was gonna survive, that took 10 years for me to get to. Even though I loved walking around New York City putting up a poster, walking another 20 feet and being able to hear people discuss the poster that just went up without having any idea I did it and getting that eavesdrop, then there was the other part of my day where I was putting my last two bucks toward a burrito [laughs]. My spirit, in terms of speaking my mind and taking risks, is the same it’s always been.”

That spirit will be in full force during the Wide Open Walls muraling event taking place in Sacramento from Aug. 9–19, when Fairey headlines a stacked list of artists all doing their part to take back the streets. Fairey will be creating a giant mural of Johnny Cash on the L Street side of the Residence Inn by Marriott, with Cash’s gaze cast in the direction of Folsom Prison. Fairey talked about his contribution to Wide Open Walls and more with Submerge recently.

Mujer Fatale | 2007

You’ve discussed in interviews and in your documentary about the aesthetic of old punk flyering and how that whole way of promotion inspired your artwork …

I think one of the things that was crucial to the underground incubation of American hardcore in the early ‘80s was that people needed each other because there was no broader support system; everybody was figuring out ways to share information about venues they could tour and sharing other resources like small indie labels. The internet has meant that everybody’s one viral hit away from a breakthrough, so it doesn’t encourage the camaraderie in the same way. I’m generalizing, because I think that camaraderie is always going to exist, but I feel lucky in a lot of ways growing up in South Carolina where there was absolutely no way of looking at being into punk rock other than completely underground or being an outsider—that kept my expectations for that like “this is not going to be something that’s going to be a career move or lead to anything with social potential. This is purely about my love for this stuff.” The moment you accept that and you’re happy with it, you won’t be disappointed that you’re going to subsist in the margins. That’s how I felt about street art. My love of punk rock and skateboarding being very outsider things made it easy for me to transition into the squalor of a life as a street artist, which somehow miraculously became something I could live off of, eventually. I didn’t have that expectation. It makes doing the work and enjoying the process without hopes for great rewards a thing you’re OK with, and I think that’s beneficial for perseverance.

Punk subculture at the time was a controversial scene. Your career in art, with guerilla installations and marketing, was also controversial in the beginning. Do you think that approaching your art in that way was helpful for you in terms of your career ascendency?

The people I was inspired by were largely people who were provocateurs: Raymond Pettibon and his art for Black Flag, Jamie Reid’s art for the Sex Pistols or Winston Smith’s art for the Dead Kennedys. Then I discovered a street artist in L.A. named Robbie Conal when I was 17 as a senior in high school—I did a year of art boarding school in California—and Robbie Conal was making these unflattering portraits of Ronald Reagan that said “Contra” above and “Diction” below, and it was during the Iran-Contra-gate. Of course, the Dead Kennedys had been very critical of Reagan, so I was already primed to see Reagan as a villain. Seeing these posters around, which were unflattering but well-painted, with a clever bit of typography, good design and were put up in the streets where they were in everyone’s face, to me that was like punk rock art. It was a step further than punk rock art in the sense that a lot of the punk rock art I already liked was stuff done specifically for flyers or album covers, and maybe the flyers ended up on the street. But this was punk rock in that it was political. Putting up big 24-by-36-inch posters on electrical boxes all over downtown L.A., that’s a strong statement and an act of defiance, and I connected with that. It was the punk rock spirit of critiquing all the dominant systems and subverting things and then mixed with me discovering people like Barbara Kruger and Robbie Conal who were visual artists doing things in public spaces with political content. For me, the thrill of going out and putting work on the street, it felt liberating. I love mischief, and I love the idea of snapping people out of the trance of repetition or accepting that you will be a spectator on the sidelines while these commercial entities put up whatever they want and the government does whatever signage they want, like it’s a one-way conversation. I was like, “Oh, no it isn’t!” It’s a two-way conversation now.

Peace Waratah Mural | Sydney, 2017 | Photo by Jon Furlong

How has that evolved? What is the balance now for your work that is sort of delivered between the more mischievous, non-commissioned street art and guerilla campaigns and the illegality of that, into now having more commissioned art projects and being given permission?

The thing that was most important to me was not just my enjoyment of mischief, but the idea that public space would showcase more than just advertising, government signage and commercial signage. It was a very gradual process for me to be given sanctioned spaces. It all was a result of me doing stuff without permission on the street. First it was people who had hip boutiques or skate shops who were like, “Yeah man, I saw your stuff on the abandoned building. Can you do something on the side of my business?” I was psyched to get those things, and some of the offers started getting bigger and bigger. The important thing to me was not whether what I was doing was legal or illegal, it was whether it was creating conversations that wouldn’t happen otherwise.

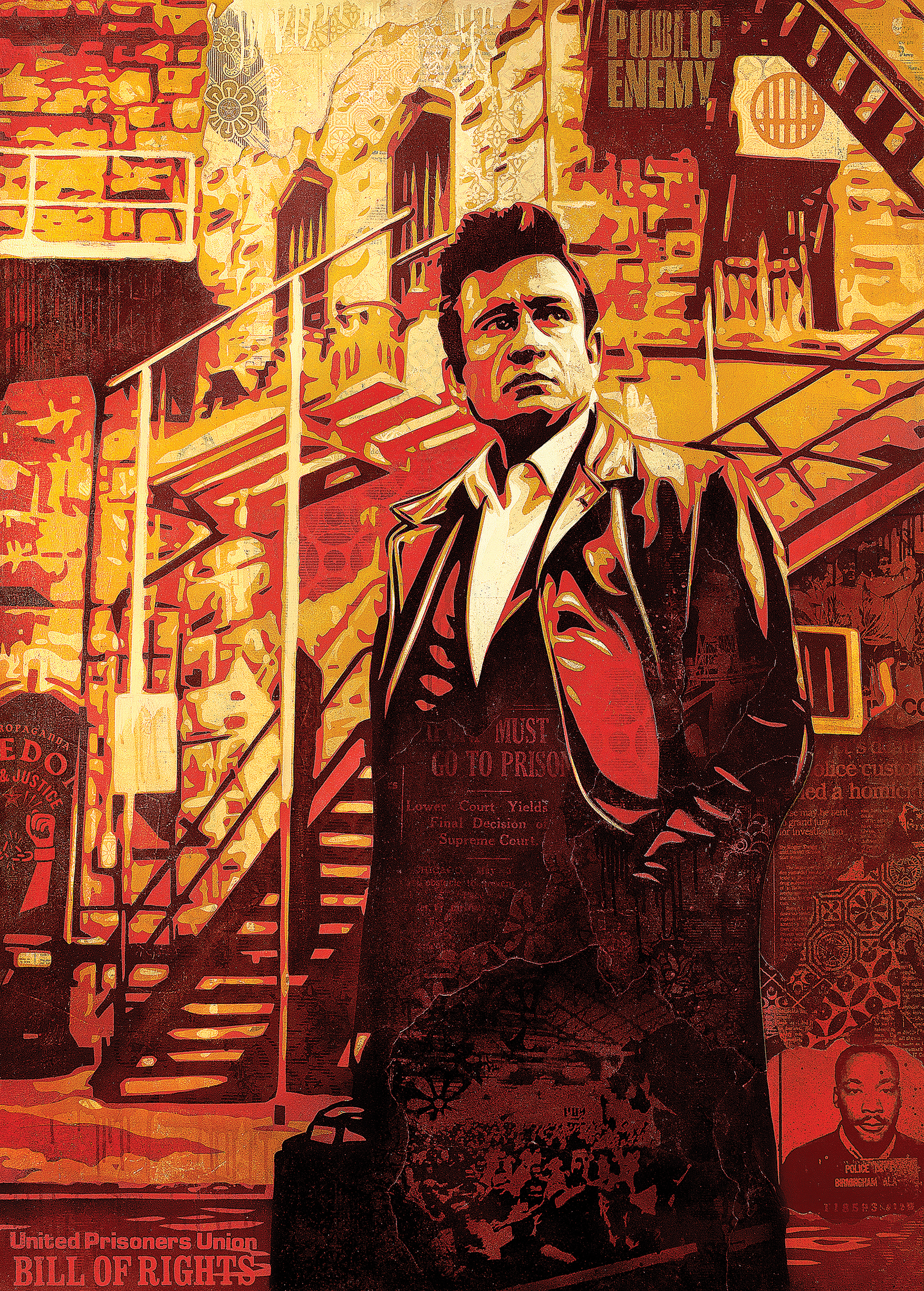

Mural to be painted on Residence Inn by Marriott during Wide Open Walls | Photo courtesy Obey Giant Art and Wide Open Walls

Getting back to the sanctioned work, for the Wide Open Walls event in Sacramento, I’m guessing the Folsom Prison connection was what made you land on the Johnny Cash piece?

Yeah, exactly. I did a project right before the 2016 election called American Civics—it was a collaboration with the Jim Marshall estate. Jim Marshall shot the Johnny Cash Live at Folsom Prison cover, but he also shot a lot of stuff around social and political issues. That series dealt with voting rights, workers’ rights, gun culture and incarceration reform. I love Johnny Cash, but I also wanted to be able to do something that talked about the need for incarceration reform, and part of the proceeds from that print as part of American Civics go to #cut50, which is an incarceration reform organization. There are still some of the prints left, large format prints and they’re pretty expensive. So doing this mural is not just a mural I wanted to do because I love the subject, but because it’s an opportunity for me to restart that conversation around incarceration reform and to point people toward the prints. It’s cool to do something in Sacramento that creates a conversation around Folsom. All those things combined were what motivated it.

Any additional info you wanted people to know about your involvement with Wide Open Walls?

The wall is on the Residence Inn in downtown Sacramento, and How and Nosm have the other side of the wall, and I’m a big fan and excited to have another wall with them. We share two sides of a really big building in Detroit, which is I think the biggest mural they’ve done and the biggest mural I’ve done. This one [in Sacramento] will be the second or third biggest I’ve done. I think it’s about the same size as one I did in Sydney—a 15-story one a couple years ago. It’s a lot of elbow grease, very labor intensive. I think unless we encounter really bad weather, we’ll be fine.

Welcome Home Mural | Costa Mesa, 2017 | Photo by Jon Furlong

Highly doubtful about that bad weather, which is great for your opportunity to see Shepard Fairey’s mural come to life at the Residence Inn by Marriott, 1121 15th St. in downtown Sacramento on the L Street side. Wide Open Walls brings amazing artists from all over the world Aug. 9–19, 2018. For a comprehensive list of events and artists, visit Wideopenwalls.org. For more information on Shepard Fairey’s work, visit Obeygiant.com.

**This piece first appeared in print on pages 18 – 19 of issue #271 (Aug. 1 – 15, 2018)**

Comments