Though Artist Victor Malagon has Moved from the Streets to the Galleries, He Refuses to be Complacent

A love of graffiti ties together three artists sharing a show at the Sacramento State University Union Gallery this month. Their colorful, fluid stories once told on cement walls are now immortalized through three different aesthetics (though still sometimes on walls) and have been appreciated by a large audience for more than 10 years.

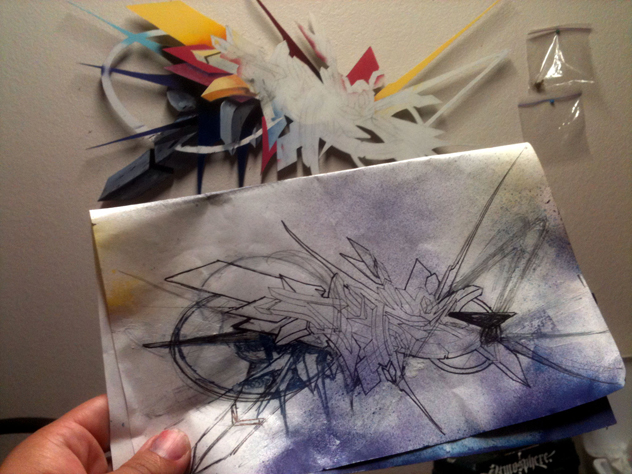

One of these artists is Victor A. Malagon, who went from can to oil paint and wall to cut wood, transforming his edgy sketches into sharp, quarter-inch-thick flat panels that trick the eye with their 3D illusions.

Malagon says the thin wood creates a sense of vulnerability that represents the artwork painted on the streets.

“Multiple hours, even days can be put in to create the artwork, but it can take seconds for it to be destroyed [dissed, covered up],” he says. “The same goes for my paintings; if not handled correctly, they can also easily be destroyed. At the same time, that kind of frailness and vulnerability is what makes them so unique and special.”

Malagon’s first exposure to graffiti occurred in high school.

“I had gone under the 7th Street bridge, a bridge that connects the south side of Modesto, Calif. to the downtown area and for the first time, I saw up close and personal the huge, colorful, wild style graffiti murals,” says Malagon, who moved to Modesto from Fremont, Calif. with his family when he was 13, and has since returned to settle there with his expecting wife. “That was it. At that time I had no idea who had painted those walls, how they had done it. I just knew that is what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.”

The successes of graffiti writers like Loomit and Delta, as well as the online global graffiti gallery Art Crimes, inspired Malagon to take his painting one step further, toward a career. However, he began work on his fine arts degree from a different perspective than his street art, with influence from the Bay Area Figurative movement of the ’50s and ’60s, and the Impasto style that uses thick brush strokes to provide texture on canvas.

“I spent a whole semester creating a body of work influenced by that style [but] at the end of the semester during the critiques, my work was basically slaughtered by the instructors,” Malagon says. “They said, ‘Why create something that has already been done?’ They were aware of my graffiti background, and they actually gave me permission to build a wall in the art department so I can paint and practice when I had free time. They said, ‘You are doing something unique with spray paint and that style… We think you should head in that direction.’”

Malagon felt disheartened and lost at first.

“I felt like they didn’t get it,” he recalls. “Graffiti to me belonged in the streets, on walls. I had no interest in painting graffiti on canvas. At that point, I felt like maybe art school was not my thing. I decided to focus that whole summer on my letter styles and painting more. I decided that I wanted to make my letter styles more unique in form. As I began to sketch and began to make my letters stretch and flow outside the page, I thought to myself, ‘how cool would this look as a shaped panel!’”

Malagon had studied the work of Frank Stella but never thought he could use Stella’s idea of the shaped canvas to his own work.

Starting in 2004, Malagon created his first pieces similar to the style he works in now. Those first pieces are different than his commissioned pieces today, with fewer razor-sharp edges and a more clunky design.

“I think that has to do with the use of tools, and learning how to use them and figuring out tricks on how to get that razor sharp and skinny without snapping or breaking the panel or cutting my fingers off,” Malagon says of the changes. “Also, as my style contentiously develops, the style changes. Unfortunately I have this attitude where nothing is ever good enough, so if I like something I did or just completed, a few hours later I start to dislike it and try to improve on it. I have been known to throw away and completely destroy paintings after spending over 80 hours on it if I feel it’s not good enough.”

Several artists from different fields and genres now recognize Malagon’s work and searched him out for commissioned pieces, including painter/designer/tattoo artist Chase Tafoya, DJ Reason, music producer Kenny Segal and Austin “Chumlee” Russell from the History Channel’s Pawn Stars.

“I have been extremely lucky with the clients I get,” Malagon says. “I’m a fan of their work to begin with. I think Chase Tafoya was one of the first people who commissioned a piece. Music producer Kenny Segal!? Are you kidding? This guy makes beats for a lot of hip-hop artists I listen to. I remember when I dropped off the painting, he was telling me that Slug from Atmosphere was at his house last week! What? I’m a huge fan of Atmosphere.”

For Malagon, the best part about his commissioned pieces is the amount of freedom he receives. Clients might say they would prefer a certain color over another, but usually he gets “do your thing, dude.”

“I do try to research my clients and try to have a connection with them through my work via color and/or form. The paintings I did for DJ Reason, and for Kenny Segal for example, I only listened to the music they created while sketching their paintings, and in an abstract way, visually represent them,” he says.

Most of the work Malagon is showing at Union Gallery is commissioned and epitomizes the internal struggle to outdo his last painting in style, complexity, shape and form.

“I pay more attention to structure and architecture now too,” he adds. “I think my work changes with my moods. Music is [also] an important element when I sketch.”

Besides his art, Malagon has also manifested his love for street art, music and tattoos into a magazine he publishes with his wife, called Refused. The two launched the magazine in 2004 when they were still dating and attending CSU, Stanislaus. It is the second coming of a similar publication Malagon created on his own from 1998 to 2003 called Burning the System.

“I did about eight issues throughout the years until around 2003. I had decided that I really wanted to publish a full-color legit graffiti magazine and worked hard to save my money to make that happen,” he says. “I remember at that time, the popular art magazines would only feature about two to four pages of graffiti, street art or tattoos. The crew I ran with had incredible amounts of talent, but at the time were not featured in any magazines because they were not ‘known’ artists.”

Refused became a national springboard for him and now-famous artists like Robert Bowen, TopR and Alex Pardee, with distribution at all Barnes & Noble bookstores. The latest issue of Refused comes out April 2014.

Malagon’s artwork, as well art by Marcos LaFarga and Ricky Watts, will be on display at the Union Gallery through Nov. 21, 2013 as part of the Possibilities Are Endless show.

Comments