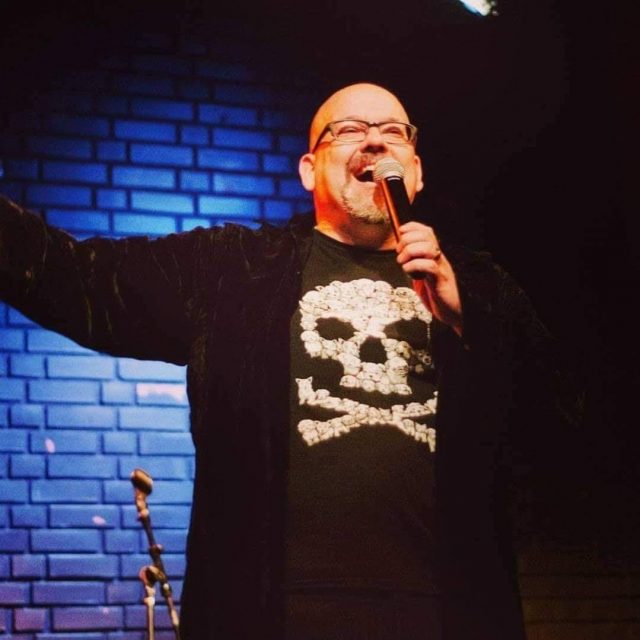

I first saw Moshe Kasher perform stand-up comedy a couple of years ago at the Punch Line in San Francisco. He’s one of those comedians who I had always heard was fantastic, but who I never had a chance to see. Within seconds, he owned the room like few comics I’ve ever seen, with a combination of great material and improvised crowd work that was brilliant and hilarious. This is harder than it appears. I’ve seen many comedians sink hard when they go to the crowd for inspiration. Moshe played that crowd masterfully, like a giant, drunk, laughing guitar. He didn’t just ask people where they worked and make fun of them like many comedians do; he used amazing listening skills to find quirks about them, and later in the show was able to refer back to things folks said earlier like a well-crafted callback. It was a goddamn work of art.

Moshe got his start performing comedy in San Francisco 17 years ago when he attended an open mic with Chelsea Peretti (currently on Brooklyn Nine-Nine) and received encouragement from Bay Area legend Tony Sparks (who’s lovingly referred to by many as “The Godfather of Comedy” and still hosts shows to this day). Since then, he’s been featured on TV shows like Comedy Central’s Problematic and @midnight, and the podcast Hound Tall. In 2012, he wrote the book Kasher in the Rye: The True Tale of a White Boy from Oakland Who Became a Drug Addict, Criminal, Mental Patient and Then Turned 16, which may be one of the most descriptive titles a book has ever had.

He recently released a three-part Netflix special, The Honeymoon Stand Up Special, with his wife (and fellow comedian) Natasha Leggero that’s a flat-out riot. They each have a solo portion for the first two parts, and the final act culminates with them performing roasts of married couples from the Austin, Texas, crowd. It works far better than I thought it would.

I spoke with Moshe on the phone to talk about his special, his book and his upcoming series of shows at the Sacramento Punch Line. Through our conversation, it was evident that he has a love of producing quality comedy and giving the audience a special show.

My 80-year-old father-in-law watches Netflix a lot, and I came out to his room while he was watching your special at the exact moment you were talking about cumming into mason jars.

[Laughs] It might be a dirty reference, but the mason jar is generationally appropriate for him. I’m sure he enjoyed it.

I love that at the beginning of your section of The Honeymoon Stand Up Special, there’s a guy in the front row who’s totally giving you a cold stare and you address it, and he just doesn’t stop. He’s acting like he was tricked into being there. Was that a weird thing to deal with, and keeping it in the special?

No, I wanted it in. The thing about doing a stand-up special is that it’s a bizarre distillation of an act you’ve been working on for months or years into a permanent state of comedic homeostasis, and somehow I perform. When I perform, there’s the material that I’ve got but in some circumstances I’m letting them dictate where the show goes. I wanted to leave it in the special because it gives a better picture of who I am as a performer. I’m 10 times more improvisational at a live show than I am in a stand-up special, except for the third part which is all improv. I was grateful that he was frowning because it was a gift that he gave me. And by the way, he laughed by the end of the night quite a bit, which is good.

I saw you at SF Punch Line. It was very improvisational, but in such a brilliant and entertaining way. I don’t think you probably planned a lot of what you said that night. It was pretty impressive.

Well, thanks. I always say the more fun I’m having, the less written jokes I’m telling. I arrive to every gig with an hour’s worth of jokes ready. but on a good night when I’m thinking about the performance, I’m thinking, “Oh, shit! I didn’t get to this … something magical happened in the room that made me run out of time.”

In the 17 years that you’ve been performing stand-up, at what point did your performances evolve to allow more of that interaction?

It’s an interesting question because I came to the stage with much more confidence than I had ability. I was willing to mess around on stage and kind of improv and do whatever thing I fancied from the very beginning. Some of my contemporaries that I started comedy with suggested, “Maybe you should focus on writing a half-hour or hour of material.” I think they were offended that I would just come up on stage and just fuck around that early into stand-up. So I retreated into the writing process and came back learning how to hone my writing voice, then again allowed myself to go with my natural instincts, which are sort of just to let whatever happens happen.

There was another moment where I realized—and this is going to sound so corny—but the way to make my job work is to remember to always enjoy myself when I’m on stage. Even when the show isn’t going the way that I want it to, I’ll figure out a way to enjoy the chaos, then the show’s going to be good, and I’m going to be good. At any rate—long story short—I’d say about five years into my stand-up career I just decided that I’m going to be a comedian that just lets whatever happen. I’ve had a lot more fun as a result.

Your personality really comes through with your performance, as opposed to someone who’s just doing material. People probably feel like you’re someone they could have a drink with and might be pretty similar to how you are on stage. Is there some truth to that?

How approachable and fun I seem by my appearance really depends on who’s absorbing it. I’ve definitely heard discussions like I’m someone you’d like to punch in the face. It depends on who you are, or your political perspective maybe [laughs]. Maybe want to have a drink with me, or punch me in the face, or both! I always say, your personality on stage is you times five. I’m also a lot more chill offstage. I’m less flamboyant offstage, too. People are impressed with how incredibly masculine I am offstage.

The Couples Roast portion of the special was very funny. It almost seems like that could be a regular TV series.

A lot of people have said that. We’re definitely not opposed to the idea. It was really cool. One of the challenges is taking that thing and making it permanent. If you’re watching it on TV you’ll say, “Sure, I bet that was funny if I was sitting there, but I don’t really care if that guy is an accountant.” The problem with putting improv and crowd work on a special is making it evergreen and relevant. I think having that conceit of us helping these couples [and] making fun of them is what made it feel like you didn’t have to be there, because we’ve all been there.

With any comedian, there’s a fear of exposing yourself and putting your work out there and hoping they laugh, but giving control to the crowd and not knowing where that could fizzle and not be as entertaining as you think.

Absolutely, and it depends on whose hands you’re in. Sometimes crowd work is disparaged because people feel like it’s the MC of the comedy club asking who’s birthday it is, but there are true masters of the form that are as artistic doing that as the best honed joke-crafter is. People like the late Patrice O’Neal, Paula Poundstone and Todd Barry are true masters of that. I consider it as big and integral a part of stand-up as joke writing. I love crowd work and I think crowds do, too. The most fun a crowd can have is watching someone make a show just for them.

What was it like to publish a book? How much time and effort and sweat did it take?

It took a lot. It’s not a typical comedian book because I had a strange upbringing going to rehab a bunch by the time I was 16, having deaf parents, a Hasidic father and a secular mother, growing up in Oakland on welfare, blah blah blah. It was very important to me, and I always wanted to be an author when I was growing up; I didn’t necessarily want to be a comedian. It was important to me that the book reflected some literary meat. In order to get there, you really have to go there, so it was definitely an emotional and intellectual and spiritual process.

Comedy is different because you’re looking for the one thing that’s the funniest … that’s not necessarily what’s happening in a book. It was important to me that it was a real book and not just a series of bits. It’s always disappointing when you read a comedian’s book, and the outline was just “write enough words to get my paycheck.” I wanted to write a book that people could read in 10 to 20 years and not know who I was and still enjoy it. It’s still the thing that I’m proudest of that I’ve ever created.

Moshe Kasher will be headlining five shows Aug. 9–11, 2018 at Punch Line Sacramento (2100 Arden Way). Tickets are available at Punchlinesac.com. The Honeymoon Stand Up Special is currently featured on Netflix, and Moshe’s book is available on Amazon, Audible and wherever fine books are sold.

**This piece first appeared in print on pages 22 – 23 of issue #271 (Aug. 1 – 15, 2018)**

Comments