Jose Di Gregorio’s celestial shapes foretell Sacramento’s bright artistic future

In 2011, I walked into Bows and Arrows to browse some clothes and ingest either a coffee or a beer. I probably had some paperwork to do, but instead of doing anything that day, I just looked at a series of paintings exhibited on the wall. Those paintings—these large black backgrounds painted on wood with blue spray-paint accents that felt like something simultaneously underwater and atmospheric supported these large, brilliant white bodies or figures that were grounded between a few rudimentary geometric patterns and curling, waving tails that loped toward the bottom of the work—those paintings were composed by Jose Di Gregorio.

Now, I don’t know much about art, but occasionally I read some people who do. From what I can gather, the only thing a good artwork should do is negate reality in some fashion. This is not to mistake the desire of artworks to be considered realistic, or to be part of the material world that we exist in, but rather that they should act as mediators.

All of that is to say, in general, art that seeks to represent in a mimetic or realist fashion bores me. Our conditions today are so much more complicated and full of possibility than some bowl of fruit or a landscape. When I first came across Di Gregorio’s work, this is what it was clearly critiquing. This, for me, was its appeal. And I can only think of about two other Sacramento artists that I have remembered in similar fashion—but I’m not writing about them here.

Di Gregorio’s works are cosmic. They chose as their subject the infinite possibilities of our universe, and they hypothesize that these coordinates and celestial bodies might offer one of two things: either hope, of the sort that only post-apocalyptic genres can allude to, or humility, of the sort that alien encounter narratives tend to provide. Maybe they do both. What’s great about Di Gregorio’s works is that they are also questions in themselves, riddles of sorts. They offer each viewer her own Rorschach test, a reflection of her inner beliefs and ideologies. They suggest that each viewer can be validated externally, and because of this, Di Gregorio has patrons from physics professors to fanatics of the everyday divine.

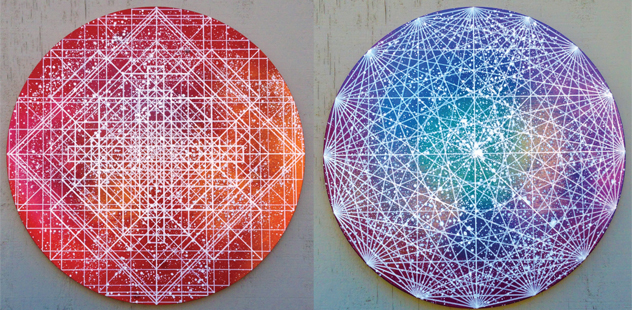

His new show, Night, will be displayed at Bows and Arrows, some two years after his previous exhibit. It’s a shift from his larger works previously available at Bows, and at the Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art, where he just had an installation. In an effort to make his works more obtainable for enthusiasts, the sizes have been decreased, but the attention to detail is evident. The cosmic influence is still apparent, but these works are essentially circles or mandalas—a term Di Gregorio uses himself, though he’s quick to separate it from any spiritual association. Each of these mandalas holds a geometric figure, some series of white lines on a nebulous background composed by specific measurements within the frame, and they offer a continuation of the thoughts I was first attracted to in his earlier work.

“There’s some sort of meditative quality to them,” says Di Gregorio. “And I’m not a spiritual guy at all.”

Each of these pieces has a different geometric rhythm, a different figure or shape that holds the frame together. The white lines are crafted, composed with detail and attention. Their initial appearance seems simple, yet the specific shapes and lines reveal a concentration, a repetitious series of paint and articulation. It is because of these recursive structures, shapes, figures and the cosmic image set, that the spiritual qualities are easy to identify.

“The spiritual nature of these pieces comes up a lot,” says Di Gregorio. “I used to be a pretty outspoken atheist. [Yet,] I feel like these works are my ways of seeing the spiritual.” This seeing the spiritual, I’d associate with the sort of focus that artists must possess, not only to create works, but to continue to create them in our chaotic, distracting contemporary. It’s a sort of satisfaction that I’ve often thought of as addiction.

One could say Di Gregorio is addicted to simple figures and infinite depth. “There’s something about drawing a white line on a black surface,” he says, and then pauses to consider it further. It’s clear at this moment that his craft has a visceral effect on Di Gregorio, that the reason he pursues art has something to do with the metaphysical experience of drawing a line. This inversion of black and white, the associations of figure and background, is part of how Di Gregorio turns the subject of his works on its head. He never finishes this thought during our time together, to tell me what that “something” is.

Instead, I might offer that space is infinite, dark, unclear. An artwork is fixed, illuminated, specific. Traditionally the canvas is light, the marks dark. An opaque background asks for figures that register as shadows, bodies, inversions of light. A pitch dark background asks for figures that register as bodies of light themselves. This is part of that negation I mentioned above. However, it’s likely not how Di Gregorio would describe his work: “I don’t have a deep philosophical notion of what I do. It’s celestial, of course.”

“When I was an undergrad,” Di Gregorio continues, “I was researching the works of Caspar David Friedrich. He was a romantic painter during the Enlightenment. He was sort of countering the Enlightenment philosophy with the idea of the sublime, how small we are. That idea of the whole.”

This influence is clear once one sees the vast landscapes and seascapes of Friedrich, the horizons that loom over the lower third of the works, the immense skies with all of their impossibilities dominating the space of the canvas. Change the subject to space, swap out the human bodies for geometric figures, add a touch of improvisation and post-expressionist impulse: this is Di Gregorio.

The subject of his works is complicated, but his continual return marks Di Gregorio’s works with a specific focus. As he explains, “Maybe I’m just fascinated with something that is hard to explain. The feeling of being overwhelmed. We want to describe it, and maybe I’m describing it visually.”

That feeling of being overwhelmed isn’t lost on the community of Sacramento. Di Gregorio recalls the recent Capital Artists’ Studio Tour at Verge Center for the Arts, where many local art enthusiasts would peek into his workroom, glance at the untraditional works, and quickly slide back out the door. He laughs, recalling a question one patron asked another Verge staff member: “Do the artists here show their works anywhere?” These well meaning sponsors of the arts, I might offer, are overwhelmed by Di Gregorio’s works as well—just in a slightly different way.

This incident stands out for Di Gregorio, having just completed an exhibition at the Indianapolis Museum of Contemporary Art. This might be the highlight of his artistic career. “It was the best show I’ve ever had,” he says. “It was all flat black, the walls, the ceiling, everything. We used red and blue light, and the works really popped. It was like a heavy-metal planetarium. I had just gone to the Lawrence Hall of Science Planetarium [in Berkeley] with my daughters. It was such a profound experience; I just wanted to mimic that. I got a budget. They flew me out. I did a mural. It was great.”

“I wish I could be an installation artist all the time,” he adds. “That is it. I got that taste.”

To go along with his recent accomplishments, Di Gregorio has recently shown at Sol Collective, designed a limited edition bottle for Ruhstaller Beer, designed and crafted a huge artwork for the recent Launch Music Festival in collaboration with others, and provided some aesthetic touches to the McKinley Park playground rebuild.

“That was over 100 hours in just one week,” elaborates Di Gregorio, “14-hour days, leaving at 6:30 AM and getting home at 9:30. Most of the work was in the mosaic, and I’m not a mosaic artist. I created this lunar/solar mosaic, and another one in the entryway. That took a lot of time, cutting the tiles and getting the right colors. People who go there always notice the lionfish. Actually, the climbing wall and the lionfish were an afterthought. It’s funny how things work. I live in the area, so it’s a humbling thing.”

Having grown up in Woodland, Jose Di Gregorio is excited to be included in the community of Sacramento. He sees a lot of possibility here: “I think that there’s going to be positive change in what happens in Sacramento art. I want to think we’re getting beyond a sculpture of a bowl, or a cowboy, like Old Sac stuff, the Wild West.”

With works from artists like Di Gregorio, here’s hoping that we might soon be recognized as stellar or even universal.

Night, an exhibition of new work by Jose Di Gregorio and Jared Tharp, will be on display at Bows and Arrows in Sacramento Oct. 4 through Oct. 31, 2013. An opening reception will take place on Oct. 4 from 6 to 9 p.m. For more info, visit Bowscollective.com.

Comments