Community celebrates fine artist Milton 510 Bowens’ 20 years of service to art and education

Beatnik Studios on 17th between Broadway and X Street blends harmoniously with Milton 510 Bowens’ latest solo exhibition, Echoes of the Sweetest Sounds.

The former is an urban loft-style gallery made of brick that brings photography, music and local artistry to a shared space. The latter is a well-honored fine artist’s resolve to educate about music, history and social justice through art.

Echoes… celebrates 20 years of Bowens’ work with pieces never before seen in Sacramento and gives a unique spin to this year’s local Black Music Month events (renamed African-American Music Appreciation Month by President Barack Obama).

In the last 20 years, Bowens has reshaped his philosophy as a fine artist and taken the approach of a community activist and documentarian. Since, he has achieved great recognition nationally. Starting in 2009, his art became part of the syllabus for a course study in the Harlem Renaissance at Cornell University’s Africana Studies and Research Center. He is also a spokesperson for the K—8 art immersion program Any Given Child in public schools across the country in conjunction with the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.

Bowens has had paintings showcased at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tenn.; been touted by local newspapers as having the largest solo exhibition (150 large pieces) in the United States in his hometown of Oakland; received this year’s Sacramento Artistic License Award; and received a resolution from the California Legislative Black Caucus for his work on arts and education in public schools.

Undoubtedly, this unconventional exhibition has a message.

“After you’ve done something for 20 years, it’s hard to choose what to show, but instead of doing a montage of random pieces…I chose those [pertaining to] music,” Bowens says, leaning back and looking relaxed on a sofa at the gallery after grabbing lunch at Slice of Broadway. “Beatnik, jazz, counterculture…it all goes together.”

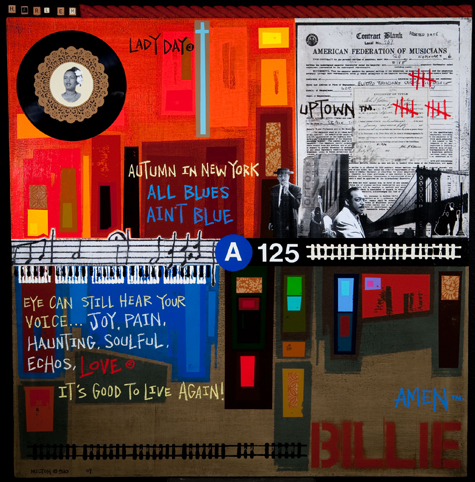

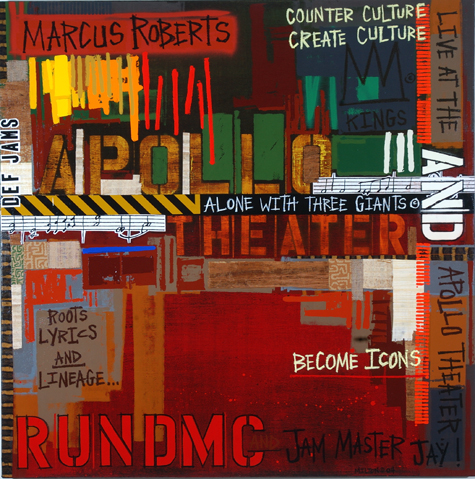

The pieces come from Bowens’ Afro-Classical collection and some from his Soul Music series. He journeys through the jazz era and its historical importance in Afro-Classical with recurring images of everything from records, piano keys and musicians’ portraits to railroad tracks, slave ownership documents and tally marks. On his pieces, he writes what he feels, quotes that he admires and pushes the viewer to take a closer look, “Don’t just hear what the work is saying, listen.”

Bowens mixes media with organic materials like cloth, doilies and prints for “richer depth and more substance.” In pieces like God Bless the Child and Straight No Chaser, the use of children’s building blocks and rope along the top of the canvas adds another three-dimensional element.

“I am trying to poetically encourage people to linger a little bit,” he says of his collages with lyricism that sometimes holds a double meaning.

Bowens says he doesn’t approach his art with a “painterly perspective,” though he has the training and knows the techniques. He attended art schools early on as a high school student in Oakland and later at the California College of the Arts and multiple schools while serving in the Army Special Forces. Two military museums collected and showed his work, and his time in the service helped shape his current philosophy.

“I was in a rapid deployment unit with special forces so I got to travel and see art I’d only ever seen in my textbooks,” he says of the experience. “Seeing it in its original environment was uniquely transforming for me. I was exposed to the fact that there is no magical pixie dust when it comes to art. I learned the definition of art–skill, emotion, spirituality, commitment–and that’s where I’m at today.”

The title Echoes of the Sweetest Sounds originally came up in 1998, Bowens says, when his philosophy and technique changed, and it has become a recurring theme.

“When I listen to music, it’s not just for its commercial appeal,” he says, working up to a more pronounced position in his seat. “There is a poetic standpoint, an emotional response. Quality music to me is like a snapshot of history.”

Take Bowens’ piece Chain Gang for instance, named for a Sam Cooke song. It has photo images of black men in striped garb imposed onto it, as well as a white man with his dogs and gun off to the left, and a worker looking down, holding a hoe to the right.

“I love Sam Cooke’s ‘Chain Gang,’ and when you start to listen to the lyrics, that could be considered one of the first civil rights theme songs,” Bowens says.

The top corner is a bright yellow, followed by bright blue and red. The bright colors sit atop Bowens’ neutral base, like all his pieces, of brown and black to portray not only his urban environment but also to hark back to the Harlem Renaissance, and before that, to slavery.

“The only true colors are what rest on top of the surface, and below that the colors are all muted,” he says. “That’s because when I went to a California museum, or the Oakland Museum…nothing there reflected my Oakland, or my California. In my paintings, you will see the gritty undertone of Oakland, because I grew up seeing concrete buildings and basketball courts.”

Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns largely influenced Bowens’ transformation as well. The artist loved Burns’ idea of taking black and white historical photographs, putting music behind them and then putting the interviews conducted in the documentary in bold color. It was the idea of combining “time, space and history” that enveloped Bowens, so much so that it was all he could do. He even went “cold turkey,” he says, on his other techniques.

Since this change, Bowens says his message is becoming clearer, his work more calculated, his compositions tighter. But the exhibition still shows his reach, including a huge drawing done completely in pencil called Ancient Musicians, a collage of jazz masters and cultural icons that brings Bowens’ collection to a detailed, pictorial climax.

Another influence is Bowens’ family. He gives his mother the credit for helping him reach his career today. Being the youngest of 10 children, and the fifth boy (hence 510), Bowens said his mother could have had less patience with him, but instead she gave the notorious child scribbler scrap paper by having his siblings cut Safeway brown paper bags for him. Bowens incorporates brown paper into his works because of this.

Now, the younger members of Bowens’ family are his biggest influencers.

“I have two special goddaughters who help me as an artist see how art can affect young people,” he says.

Bowens works with goddaughter Mizauni, a second-grader, spending time with her as she learns to read and write. She recently won her school-wide reading competition and her family has seen “amazing success” in her educational ability since the two have been spending time together.

“I want to model what I’ve done with Mizauni to help hundreds of children in Sacramento,” Bowens says. Sacramento became the pilot city for Any Given Child, in which Bowens helped place local professional artists in schools to provide an integrated art curriculum and one-on-one interaction with students. Schools in other parts of the state, as well as in Portland, Ore., and Las Vegas, are following suit.

“We take what they are studying, like California history or ancient civilizations, and add art as a teaching mechanism,” Bowens says. “Studies have shown that students have better retention of information this way, instead of just memorization.”

Bowens says he is working toward other projects with youths, including starting a mentor diversion program in Alameda County with the juvenile court system and an art and literacy campaign in Sacramento.

“I’m getting ready to rival [my largest exhibition in Oakland] with the Art of Storytelling exhibition that will engage a program for fine art and literacy, specifically one for third grade literacy,” he says.

Bowens is basing the program off a study that upcoming correctional facilities decide on the number of beds they need by looking at the local third grade reading level.

“It’s not something terrible, it’s just if we see a problem coming, we need to prepare for it,” he says. “We need to get involved now. I’m not a minister… I’m not a counselor, I’m a painter. But I believe I have the skills to make a change and inspire young people to read.”

Some messages like this one are loud and clear in his work, while others take a little longer to see. But that’s the beauty of contemporary fine art, and though Bowens says his art “isn’t to decorate, but to educate,” he adds that he does enjoy seeing it hanging on the walls.

To catch Echoes of the Sweetest Sounds, visit Beatnik Studios at 2421 17th Street by June 26, 2012.

Comments