Pressure Point Celebrates Sweet 15

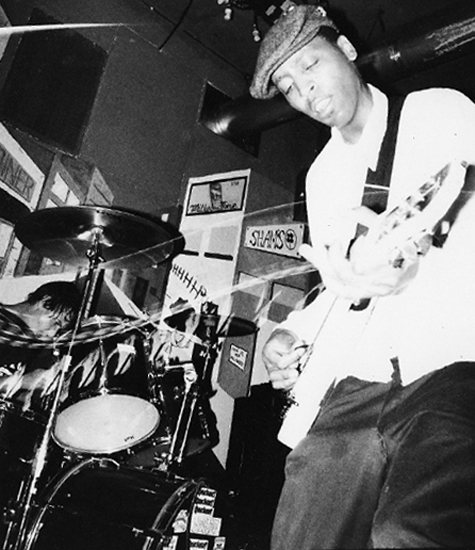

This year, Sacramento’s own street punk/Oi! prodigies Pressure Point will celebrate their 15th anniversary. An impressive feat in its own right—especially considering the tumultuous nature of the punk rock scene—what makes Pressure Point’s quinceañera even more notable is that they’ve managed to survive on their own terms. Though Pressure Point has shared stages with punk rock giants such as Rancid (Lars Frederiksen acted as their producer on two full-length albums and a 7-inch) the band has managed to survive, and thrive, in what lead singer/cofounder Mike Erickson calls an “underground within the underground.” To commemorate their 15th birthday, Pressure Point will release on Sept. 30 Get it Right, an anthology that re-imagines some of the group’s earlier material and includes a few new songs and covers. Before heading out on a tour that would take them to the Midwest and back, Mike met with Submerge to discuss the new release and the difficulties in bridging punk rock’s generation gap.

You’re heading out on tour pretty soon. Do you want to talk about that a little bit? Is it to promote the new album?

Sure. Honestly, one of the biggest reasons that I like to be in a band is that I get to travel, and it’s an unconventional way to see America. I see America through the eyes of people like me. It’s not a tour guide or a travel agent. I get to see this country through the eyes of people who are similar to me, who I enjoy being around, and have similar beliefs and philosophies. We’re not only touring to promote the record, but you know, it’s summer time. It’s a good excuse to get out and be with your friends and have a good time.

How have you seen the country change in the time you’ve been touring with Pressure Point?

In terms of the punk scene, the scene that I’m a part of, things have changed drastically since we started. There are still people like”¦Anti-Heroes and Agnostic Front—people that we met real early on who are still out there doing it and have the same beliefs and the same attitudes. But what I saw, with really good bands like Rancid—who were able to break through and bring what I consider legitimate punk rock to the masses—the aftermath of that was that every label wanted to get their own Rancid. They wanted to make even more money. They would get their carbon copies. They wanted to dumb them down. They would water them down, sweeten them up, so they could be more mass-produced. And there were some bands that were willing to play ball. When those bands did that, it watered down the punk scene at large and began to split it.

With the latest release, you guys are revisiting older material. What was that like for you guys?

A lot of the material was written by Kenny [guitar] and I really early on. When we started this band, we struggled to find the right fit with the different members because of the style we played. The approach we had and the type of politics we had were all really unconventional, and to be honest, kind of dangerous for this town. There weren’t a lot of promoters or record labels that were willing to work with us, and that was true all over the country. Pretty soon, we were able to connect and hook up and an underground within the underground developed. Because of all that, we always heard the songs a certain way when we wrote them, in our minds’ ear, but it never really came out on tape like we wanted them to. Over the years, we’ve had good friends and good band members and we’ve got the Nates [Hat and Mohawk, bass and drums respectively]. We’re turning 15 years old this year, and we wanted to celebrate that, so we went and revisited a lot of material, and now we were able to update it, refresh it and record it so it sounded the way we originally heard it.

Other than rerecording the songs, did you revamp them in any way?

That was a debate within the band. We decided that we were going to do the things we needed to do to make the songs better. Lyrically, I decided I’d leave the songs alone. There were a lot of lyrics that were really naïve when I wrote them. I wrote some of those songs in my early 20s, but I decided that they capture a time and a place and that I should just leave them alone. Musically, we altered and changed some of the songs.

Before you mentioned the songs you were doing were dangerous for the area. What did you mean by that?

Sacramento in the mid-’90s, the punk scene was kind of smoldering. It was suffering from a lot of things left over from the ’80s. Within the scene in the late ’80s, early ’90s, there were a lot of Nazi skinheads that were left over, and they were threatening the entire punk scene at large, so you had that violence and that danger, and then you had on the other side of it people like Kenny, people like me, who grew up in Sacramento lived in Sacramento, lived through that, and were battling, of course, against those kinds of notions. So for us being a straight up Oi! band, a street-punk band, a band that espoused a skinhead philosophy and attitude—of course a traditional one—a lot of promoters around here got scared. A lot of them said, “Oh, I don’t want that.” We were never ones to look at the problem and just sweep it under the rug. We confronted it head-on, recognized it and dealt with it. They were afraid there would be trouble at gigs, that if they put us on bills, it would draw them [Nazi skinheads] to shows. These guys were coming to shows anyway. We did our own shows, and now we have our own scene. It’s fresh and vibrant. We don’t have those same problems, we don’t have those same issues, and over the years, we were able to hook up with a lot of national acts that were really getting big, and if it wasn’t for them demanding that we get on bills, a lot of the promoters around here would not work with us.

For the new songs you wrote, could you talk about those lyrically?

One of the new songs on the record is “Fuck the Kids,” and it’s a hardcore song in the tradition of New York style or early ’80s style. The American landscape early on, there weren’t many divisions. When we went to shows, you’d have Reagan Youth playing with Bad Brains playing with Sick of It All playing with Gorilla Biscuits. So you’d have straight edge bands playing with skinhead hardcore bands playing with more leftist punk bands. Everyone had a lot of respect for each other and just did their thing.

It seems that over the last 10 years, especially the last five, there’s been a lot of sectioning off and divisions within the scenes at large. I noticed that as a skinhead that me and a lot of my punk rock friends would go to hardcore shows, because we really appreciate that kind of music, and the kids would shun us like we didn’t belong there because we didn’t look like them. And that with the infusion of metal made it so that it wasn’t really connecting with where it came from or where it was”¦or what it is.

I wrote a song called “Fuck the Kids” and Kevin Seconds from 7 Seconds sang on it. I asked him because they were pioneers of the original West Coast hardcore movement, which had more of a positive vibe, bringing people together. Even though we’re not a posi band, we have a similar attitude. It’s about taking people who are outside of mainstream society, or the people who at least don’t fit necessarily. They don’t want to fit”¦they would find their way in this other scene at large as individuals, and that seems to be lost. There seems to be a lot of conformity, a lot of packaging, a lot of formulaic nonsense within the hardcore scene, and it happened in the scene of music we play, too, in the late ’90s, and I think in a lot of ways that’s what killed it. And whenever you lose that identity, you lose that ability to sound original or to be original or to think on your own, then you lose touch with where you came from, and that’s why I wrote “Fuck the Kids.”

Why do you think that the fractioning of the scene has happened?

I think it’s largely people like me who are to blame for that. I’m 38, and I don’t think people my age were as vigilant as they should have been, or maybe in some cases as welcoming as they should have been to the new generation. I also think that, again, hardcore broke and record labels were like, “Oh, package it, sell it, it’s all about money,” so you had a lot of bands that sounded the same, and a lot of kids glommed on to it. The attitude became more of a mob mentality as opposed to a punk mentality. When I overhear people who are into hardcore—and I’ve overheard them telling Kevin Seconds that 7 Seconds isn’t a hardcore band—that’s the attitude right there that I’m talking about.

Comments