Thoroughly punch-drunk from being hand-led from one Marvelized CGI spectacle to the next over the past 10 summers, I thought I’d take a gamble on an Indian blockbuster film this week, a new Tollywood (Telugu-language) hit entitled Bharat Ane Nenu (I, Bharat), playing in select theaters in the Sacramento region. What could be further from Avengers than a three-hour musical epic about a young hero standing up to corrupt regional politics?

As it turns out, a viewer trading a Hollywood experience for a Tollywood one is also trading one set of fairly entrenched industry expectations for another. Yes, musical numbers are requisite, even amidst grim subject matter; yes, the masala factor is cranked up to its highest notch, allowing political drama and superhero action to mingle with rom-com antics and shameless tear-jerking; and yes, all these elements unfold in a whirlwind of smash cuts, zooms, rapidly sped-up and slowed-down photography, and other incongruous razzle-dazzlery. Such an experience is an invitation to take leave of the senses and allow them to be overtaken. Taken out of its national context, the film is still very enjoyable, but as Bharat … wears on, it becomes more fascinating for its philosophical implications than its overstuffed series of set-pieces, which increasingly seem like mere window dressing for a strident, and possibly dangerous argument concerning the role of absolute power in shaping society.

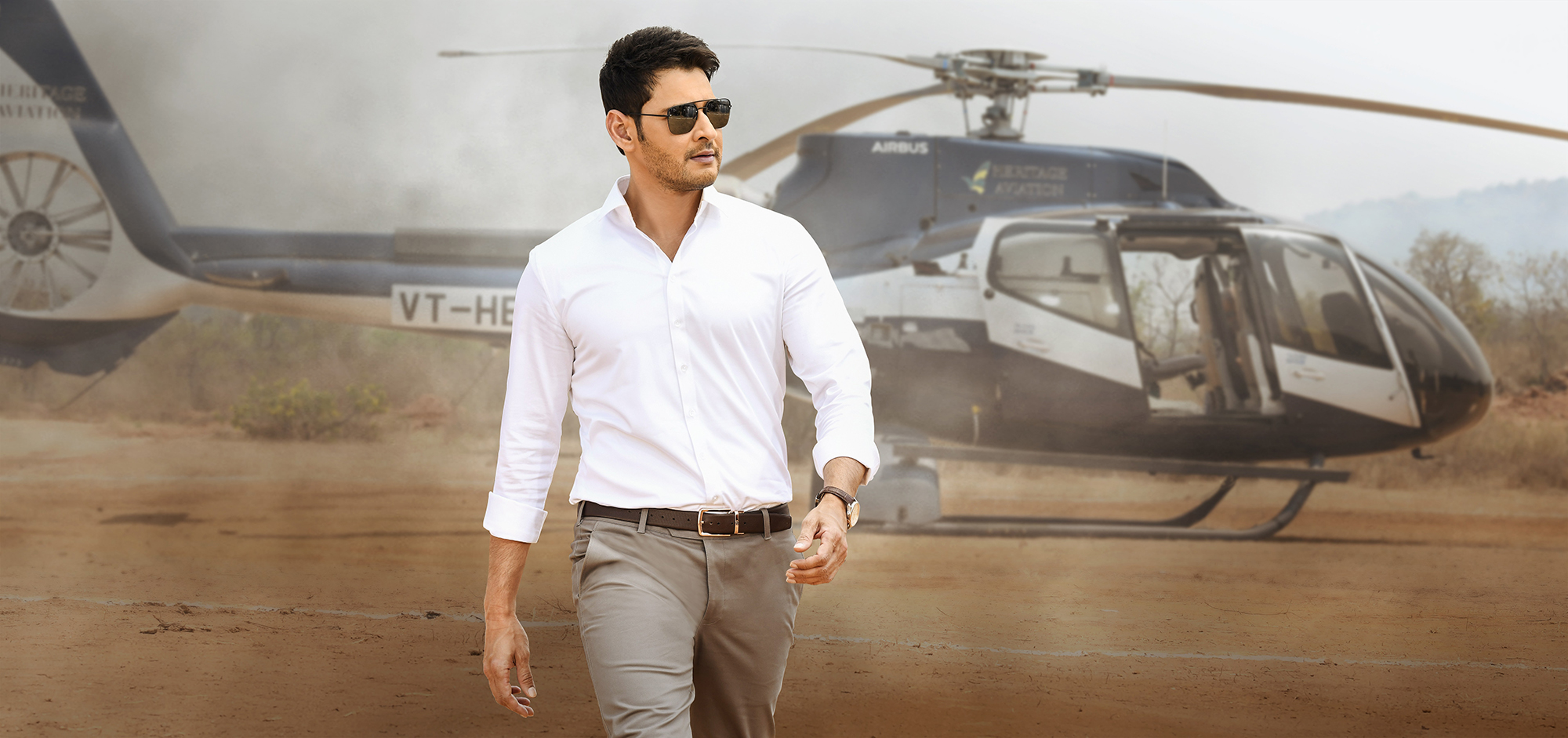

Mahesh Babu (“The Prince of Tollywood,” Telugu cinema’s main attraction for many) stars as Bharat Ram, fresh out of university (and convincingly so for a 40-something actor) in Spain, where he has just collected five degrees. In spite of this, he proclaims his unquenchable thirst for more knowledge in a hot flamenco dance number. Having lived most of his life in Western Europe, he is whisked back home to the state of Andhra Pradesh, where his recently deceased father, Chief Minister (akin to state governor) lies in state. Flashbacks reveal a sad tale of estrangement and family sacrifice—though his father was a good leader, he was basically a stranger to Bharat due to the pressures of governance, and now Bharat’s home state is a strange land to him as well. With this in mind, it’s hard to ignore the bizarre ease with which his father’s adviser (Prakash Raj) appoints him the new Chief Minister.

The rest of the film follows an increasingly godlike, perpetually smirking Chief Minister Bharat as he goes about solving the intractable societal problems of urban and rural India. After being frustrated by the chaos of trying to drive an SUV through Hyderabad, he decides to exorbitantly raise the fines for minor traffic violations up to the average monthly salary of a local. “This is a society,” he says. “Everyone should have fear and responsibility.”

Though there is a clear deficit in the quality of the subtitles, the gist is clear enough. We are witnessing another variation of an undying myth—the incorruptible leader whose strength and beauty are their own virtue, whose heavy hand guides the nation, to whose authority rich and poor, powerful and meek are equally subject, whose words bring a tear to the eyes of the adoring public, whose widely trumpeted humbleness and subtle wisdom is towering to the point of being oppressive. It is a strange and queasy brew of starpower, paternalism, idolatry, political fantasy and violent wish fulfilment. Its manic lack of tact has led me to reflect on similar tendencies in our own national cinema.

From fighting school privatization to (ironically) preventing nepotism in a district election, after which Bharat dances with the townspeople during a local ceremony while they proclaim him to be “a living lord,” the film dips wildly between trying to tick all the fan-pleasing boxes while bullishy pushing forward its incoherent views. There is no telling when the Chief Minister will lay down the law by roughing up corrupt officials (wielding a concrete block with a rebar handle like a cricket bat), or when he’ll take the more soft-handed approach (putting the concept of Panchayati Raj—allowing a degree of self-rule and local budgeting to the villages—into practice). In either case, the one constant in this film is a celebration of omnipotence, arrogance and narcissism. When such an attitude prevails, it will not matter for long whether the figures and good intentions we’re praising are heroic. The muscles we use to exercise judgment will quickly atrophy.

For a better example of what contemporary Telugu cinema has to offer (and an example of fantasy put in its proper place), try S. S. Rajamouli’s excellent Baahubali saga, both parts of which are on Netflix.

{2 out of 5 stars}

**This review first appeared in print on page 11 of issue #265 (May 7 – 21, 2018)**

Comments