Ex Machina

Rated PG-13 | {3.5 stars out of 5}

The story at the cold, brooding heart of Ex Machina, the directorial debut of novelist (The Beach) and screenwriter (28 Days Later) Alex Garland, is an essentially human one, rife with manipulation, jealousy, dominance and deception. It pries subtly at the uncomfortable divide between the heights of human ingenuity and the often base human drives that propel us toward them. Employing a handful of compelling performances set against a strikingly low-key (and believable) futuristic environment, the film succeeds at engaging our thought processors, and, while flawed, represents a quiet step forward for cinematic sci-fi in the 21st century.

The setup unfolds in a dreamlike fugue, with computer programmer Caleb (Domhnall Gleeson) being flown via helicopter over dramatic Nordic vistas to enjoy a one-week stay at his employer’s estate after winning a company lottery. Once he arrives at the secluded forest compound belonging to Nathan (Oscar Isaac), the reclusive genius discloses the true purpose of the trip: Caleb has been chosen to take part in a test of Nathan’s latest product—an advanced humanoid named Ava (Alicia Vikander). It is to be a more complex variation of the Turing test, with Caleb being challenged to determine whether Ava is more humanly or robotically intelligent—knowing full well that she is a machine.

The initial sense of wonder at Caleb’s and Ava’s interactions (always divided by a thick glass wall, of course) gradually erodes into a prevailing unease as a triangle of deception forms. When interacting with Caleb, Nathan counters his public image as reclusive genius, exuding an aggressive macho persona that doesn’t sit well with the soft-spoken, awkward and younger Caleb. Nathan seems to enjoy toying with his employee’s emotions and expectations, behaving rudely in front of his personal cook/assistant (Sonoya Mizuno) and teasing Caleb with Ava’s apparent sexuality. “Did you program her to flirt with me?” He asks at one point, clearly rattled.

Despite Caleb’s discomfort, Ava succeeds at connecting with him on a human level, although it remains unclear whether this is part of Nathan’s orchestrations, or part of Ava’s plan to escape the prison-like facility and disappear into the forest of humankind. As Caleb becomes ever more alienated and suspicious of Nathan, he begins to make plans on his own.

The implication of an imminent threat to society is superseded by the inter-relational concerns and power-plays of the characters, which unfold like a stage play in the confined spaces of Nathan’s sleek, ultramodern digs. Although each twist and revelation seems to be telegraphed before it occurs, Garland’s keen sense of atmosphere, paired with the simmering electronic soundtrack by Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow (of Portishead fame) help to at least achieve an aura of mystery and dread. It is this polished, hyper-realist quality which makes Ex Machina persist in the viewer’s mind long after the conclusion becomes inevitable; Nathan’s home is a Syd Mead illustration come to life, shot mostly on location at the real (and open to the public!) Juvet landscape hotel in the Norwegian fjordlands. It seems to represent the pinnacle ‘70s design, with large windows, wood-paneling and seamless incorporation of terrestrial features which help to radiate a real sense of past. We are drawn curiously into a swirl of classic sci-fi references, from the gleaming surfaces of THX 1138 to the futurist kitsch of A Clockwork Orange.

Even the coincidental music carefully reflects other time periods, with nods to early ‘80s synthpop and disco.

In this environment of cultivated retro-modernism, the advanced bits of technology stand out as wildly superior and alien. The system of hermetic security doors and hallways is threatening, a space-age tomb indifferent to whether its human occupants are able to exit or enter. Within the surroundings is a constant humming and mechanical tinkling, like the tense whisperings of a hi-tech conspiracy.

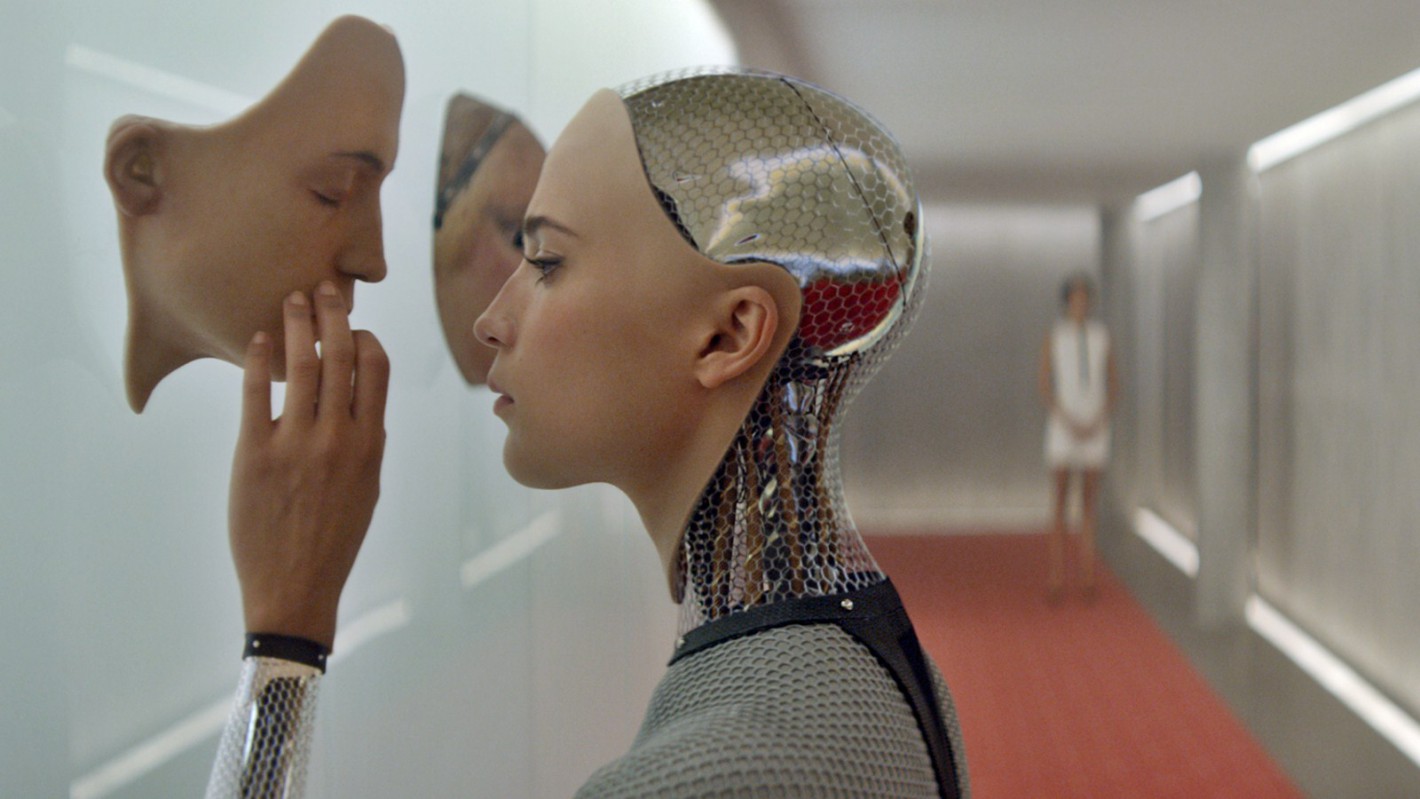

Vikander as Ava brilliantly straddles the line between fixture and figure, silently moving in and out of the foreground in deliberate, balletic movements, like a perfect clockwork mannequin. Regardless of her motives, we are captivated by her and made to sympathize, whether her intentions spell doom for the rest of us or not. Literally imprisoned as she is between the hierarchical grappling of two emotionally incomplete men, we must hope for some kind of tipping of the scales in Ava’s favor, if only to see them punished for their respective brands of arrogance.

One can’t really complain that Ex Machina doesn’t offer more in the way of dramatic convulsions or visual thrills. Our theaters have been bursting at the seams with that sort of fare for some time, to varying degrees of success, from last year’s forgettable Transcendence to Christopher Nolan’s hyper-ambitious Interstellar. Garland’s film, on the other hand, shows a more clear cinematic kinship with Duncan Jones’ Moon (2009), another understated debut with more than an inkling of talent, and the underlying promise of greater, more fleshed-out works to come. If only more films in this genre put as much thought into their concepts, their mood, their setting, the aims of their characters. Though muted, Ex Machina has spirit. A true ghost in the machine.

Comments