Why Lie? I Need a Drink

What if that grimy looking guy who just asked you for change really wasn’t homeless at all? What if, at the end of the day, he hops in his BMW and shoots straight out to his home in the burbs, or his vacation home in Tahoe? Is it possible to make more money panhandling than you can by, say, cooking fries at McDonald’s or some other thankless, albeit honest, gig? It’s questions like these that are explored in Sacramento-based comedian Keith Lowell Jensen’s documentary, Why Lie? I Need a Drink, which is due out on DVD next month.

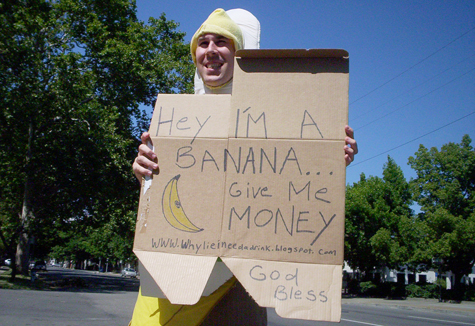

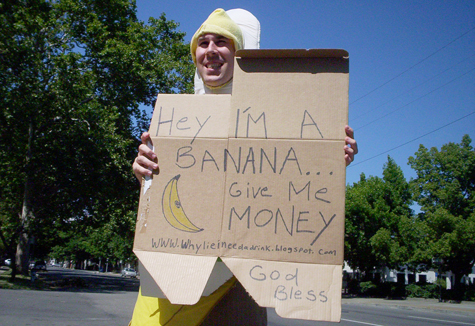

Known locally for his work with the I Can’t Believe It’s Not Comedy sketch troupe and also as part of the Coexist? Comedy Tour, Jensen gets the documentary off to a goofy start as he tries to discover if one can really make a good living from begging. He takes to the streets to get a first-person look at the world of panhandling, and at first his approach flirts with the absurd. He dons a variety of costumes from a banana suit to mime makeup and arms himself with an arsenal of wacky signs–always punctuated with a “God bless”–to see what combination will earn him the most money. The absurdity reaches its peak when a man dressed in swimmies and goggles and wielding a pool noodle chases a banana-clad Jensen around a freeway off-ramp.

In addition to begging the old fashioned way, Jensen also takes panhandling into the cyber age. He sets up a website where people can send him spare change, cold calls people whose numbers he finds on the Internet and even culls Yahoo chat rooms for those who may be sympathetic enough to dig through their pockets.

The humor sweetens what can be a bitter pill. Jensen and company, for all their shenanigans, present a well-rounded view of panhandlers and how we treat our homeless. Interviews with both the beggars and the people they encounter run the gamut of emotions. One young man vents a lot of anger and resentment toward beggars, saying he’d like to spit on them; while another, perhaps of similar age, speaks from his past experiences with life on the street and says that he always tries to give money to those who ask. The film simply presents these arguments without showing its hand one way or the other, and for that, it’s to be commended.

Things seem to hit home for Jensen when he decides to ditch the costumes and go out panhandling in his regular clothes. One scene in which Jensen is begging in front of a post office in Roseville around Christmas time is especially effective. Shot with a hidden camera, a postmaster attempts to chase Jensen from the area while he pleads and protests that he’s got every right to stand there because it’s federal property. Though it’s obvious that Jensen is not destitute, it’s easy to imagine such a scene playing out in any town in America. As it turned out, the spot by the post office was Jensen’s most lucrative location, netting him upwards of $30. Most times out, however, he hardly earned enough to buy a cup of coffee.

Why Lie? I Need a Drink may not be the most hard-hitting examination of homelessness in the United States, but it’s certainly a humane one. It paints an elegant and entertaining portrait of life on the streets, how the homeless are perceived and the murky legality that surrounds panhandling.

The film was shown in theaters around California, including the Crest in Sacramento, and even as far east as Albany, N.Y. On Nov. 4, 2010 the filmmakers will return to their hometown Crest Theatre for the Why Lie? I Need a Drink DVD release party. Admission is $15 and will include a copy of the DVD. Extras on home video release include a neat interview with Jensen conducted by local personality and horror host, Mr. Lobo, as well as a handful of deleted scenes.

For more information or to pre-order the DVD, go to www.whylieineedadrink.com.

Click the image above to view the trailer for Chris Rock’s newest comedy/documentary Good Hair. Here’s a snippet from the synopsis:

When Chris Rock’s daughter, Lola, came up to him crying and asked, Daddy, how come I dont have good hair? the bewildered comic committed himself to search the ends of the earth and the depths of black culture to find out who had put that question into his little girl’s head!

The film is directed by Jeff Stilson and features interviews with Paul Mooney, Ice T and Maya Angelou, amongst others. From the trailer, it seems like this one’s going to be a winner…in fact, it already won a Special Jury Prize for U.S. Documentary at this year’s Sundance Festival. Good Hair will open Oct. 9 in select cities and Oct. 23 nationwide.

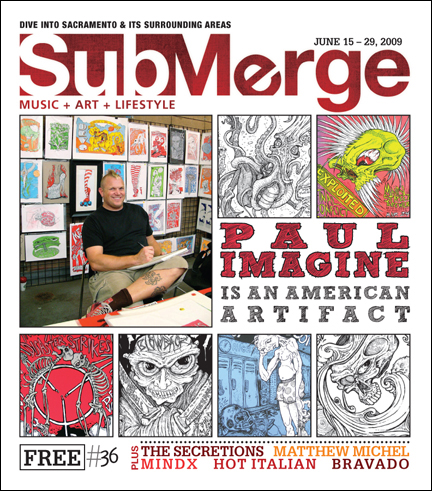

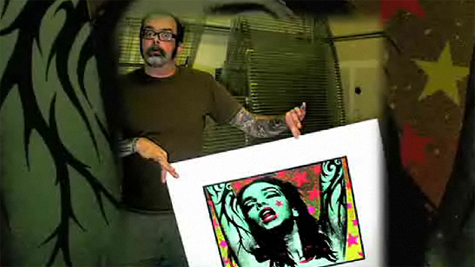

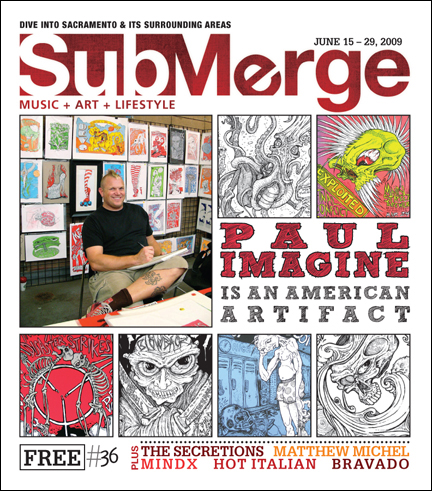

Sacramento Rock Poster Artist Paul Imagine Featured in Documentary

No matter what uptight musicians will have you believe, music is not all about the music. Image is important. If you don’t agree, go to any concert in any bar, club or arena anywhere in the world. Chances are, the look of the crowd will mimic that of the people on stage.

It’s nothing to be ashamed of. Hey, if you can cram yourself into a pair of skinny jeans, good for you. Humans are just visual creatures. But the images we associate with the music we love doesn’t have to be as superficial as the right pair of sunglasses or the ironic value of a T-shirt. What we see can actually—and should—enhance what we hear. And if those images say something about the time in which the music it represents was created, then all the better.

Documentarian Merle Becker has long had a fascination with the iconography surrounding music. A self-described “obsessive music fan,” Becker’s first job out of college was working for MTV’s embarrassingly seminal ’90s cartoon program Beavis and Butthead. She worked alongside the person who selected the music videos shown in each episode.

“I was going through the MTV library looking for obscure and bizarre music videos,” Becker admits. “It was basically 9-to-5 watching music videos, which I loved, but I think anyone else would probably have slit their wrists.”

If nothing else, her work with Beavis and Butthead only seemed to strengthen her draw to the imagery of music. Fast forward to 2004—years after the misanthropic animated duo uttered their final, “Heh, heh”—when in a book store, Becker stumbled upon The Art of Modern Rock, a coffee table compendium of rock poster art. Though she admits she wasn’t a collector or even a fan of the genre prior, the book certainly piqued her interest.

“That was the first time I was aware people were still doing [rock posters],” Becker says. “I thought the ’60s had happened, and I didn’t realize people were even still doing them.”

She was so “blown away” by The Art of Modern Rock that she decided to delve deeper into the world of rock posters. She left her job at MTV and embarked upon a four-year journey that culminated in American Artifact: The Rise of American Rock Poster Art, a documentary that follows the timeline of American rock poster art from its birth in the 1960s.

Merle Becker

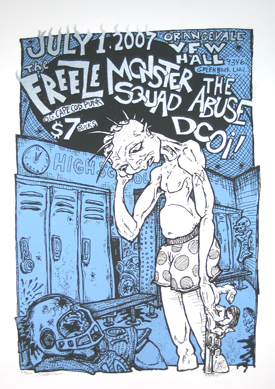

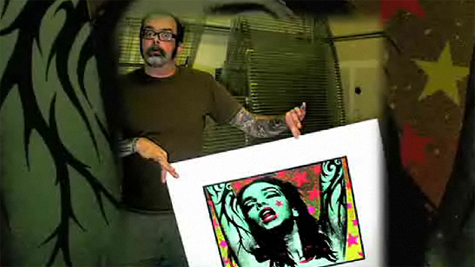

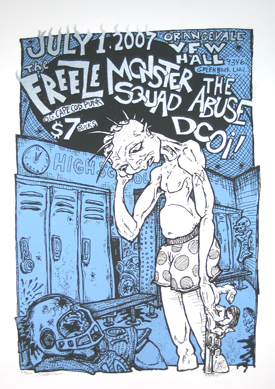

American Artifact interviews collectors and also some of the genre’s most notable names, spanning decades, including Stanley Mouse, Jermaine Rogers, Frank Kozik, Coop and Tara McPherson. These artists have created posters for bands such the Grateful Dead, Death Cab for Cutie, Green Day, Tori Amos, Pearl Jam and many others. Also featured in the film is Paul Imagine, a Sacramento rock poster artist who has worked for bands that he admits, “Most people don’t know.”

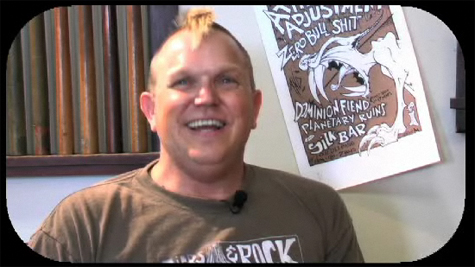

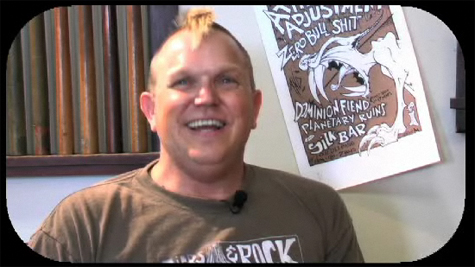

“The thing I love about Paul is he’s always laughing,” Becker says of Imagine. “I don’t think I’ve ever talked to him when he wasn’t giggling. When I was putting the film together, it was a lot of fun to go through his footage, because he’s always joking around and laughing and giggling. We would sit in the edits and start giggling with Paul.

“He has done a lot, and is very active in his local scene,” Becker continues. “Not just with his poster art, but putting on shows, and bringing other poster artists to do shows in Sacramento. I was drawn to him because he’s so active, his work is so fabulous and he’s just a funny, super nice, giggly guy. And he said some fun stuff in the film. His quotes always seem to get a laugh from the audience.”

Submerge interviewed Imagine via phone from his home as he was “chilling and just checking e-mails.” And, as Becker suggested, he laughed quite often as he explained how he got into creating rock posters and got involved with American Artifact.

Imagine credits heavy metal album art as one of his earlier influences.

“I used to draw Eddies from Iron Maiden everywhere,” Imagine explains. “When I was in high school, I was a big metal head.”

However, it was in the punk scene that he eventually found a home. Originally, Imagine wanted to be a musician, but soon realized he “had absolutely no talent for it.” But being active in the scene, going to shows through out the ’80s and ’90s, he found another way to contribute.

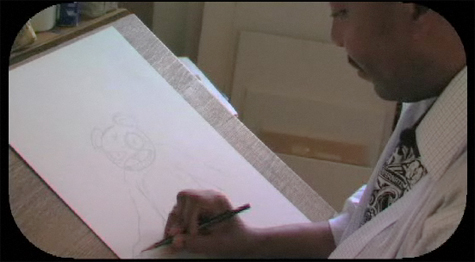

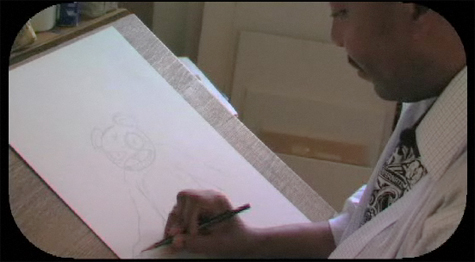

“I met a lot of bands, and they needed fliers, and it went from there,” Imagine says. “I started doing friends’ bands and photocopied fliers. I’d learned how to screen print, because I wanted to put my artwork on T-shirts.”

It wasn’t until around 1999, when he attended a rock poster show in San Francisco, that he graduated to screen printing rock posters.

“I actually talked to some of the artists like Firehouse and Chris Shaw, and I was blown away,” Imagine explains. “I was like, ‘Dang, I can just start printing posters instead of photocopying fliers,’ and right after that, I

just started.”

Since then, Imagine has managed to gain some measure of notoriety in the underground world of rock poster art without creating images for big names in the music world. Though he’s not entirely opposed to the idea.

“I would have to love them,” Imagine says of the possibility of working with marquis music acts. “I don’t listen to radio bands and stuff. I mean, if Iron Maiden wanted a poster from me, I probably couldn’t turn that down. I stick to shows that I would want to go to. I don’t go to the big auditorium shows. I stick with the punk rock bar shows and small clubs. If I don’t want to go to the show, I won’t do a poster for it.”

A lot of his aversion to working with major music acts has to do with his distaste for working under restrictions. Perusing Imagine’s art, you’ll find bizarre creatures, chaotic lettering arrangements and plenty of skulls—a freewheeling, outsider aesthetic befitting the bands (such as Melvins, Diseptikons and Secretions, also featured in this issue) Imagine chooses to work with.

“I don’t like the bigger shows where you get art directed,” Imagine says. “I can’t handle being art directed.”

Imagine got involved with American Artifact at the behest of The Art of Modern Rock co-author Dennis King, who suggested the artist to Becker. Imagine says he was surprised to be contacted.

“I’m always surprised when this stuff happens,” Imagine says. “Any of the books I’m in, I’m like, ‘Woah, I’m in!’ To get into this, with so many incredible poster artists out there, is pretty amazing—especially since my style is not quite mainstream. All the posters I do are for small label, no-label, touring punk rock bands, so I don’t have the whole, ‘Well, I did posters for Van Halen!’ thing going on.

“When I get asked to do these things, I just go along with it, and figure somebody made a mistake along the line,” he adds with a laugh. “I don’t want to alert them to their mistake.”

Mainstream or not, Imagine certainly holds an important place among the canon of rock poster artists. And while the genre has been labeled “lowbrow,” rock poster art, as Becker asserts during our interview and in the course of her film, should be “preserved”¦and celebrated,” she says. According to Becker, the work is important because it is an “artifact of the time period that it came from.”

“A hundred years from now, when you look back at the art that was coming out from the period, you’ll be able to look at the rock posters and see a little bit about what was going on in the underground and the political views of the artists at the time,” Becker says.

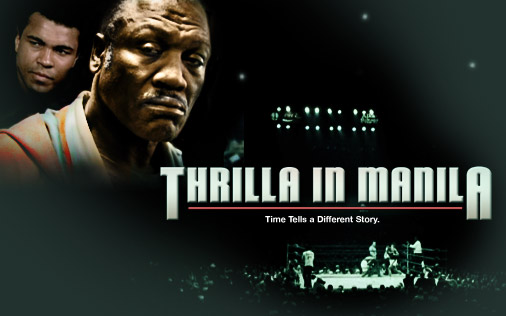

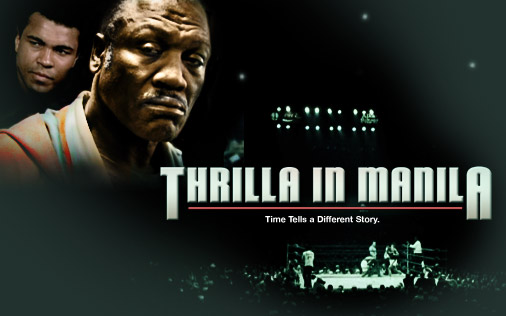

Thrilla in Manila is a new documentary currently airing on HBO. It follows Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier from their friendship to their falling out to, eventually, their third and final bout in Manila, Philippines. Whether or not you’re a fan of boxing (I am), it’s definitely worth checking out.

Ali is one of the most revered figures in sports, and for good reason. Not only was he one of the flashiest, most decorated and outspoken athletes who ever lived, he also challenged America’s view of race during one of America’s most tumultuous times. Ali deserves the respect he gets. To many, he was a hero, and I would suspect that even those who cheered against him owe him begrudging respect.

But if comic books taught me anything, a good hero is nothing without a good enemy. Enter Frazier, Ali’s most bitter rival.

The documentary focuses mainly on Frazier, the less loquacious of the two boxers. It also shows a side of Ali many may be apprehensive to acknowledge: a dark and troubling side. Ali, known for his verbal (and physical) bravado, may have delighted fans with his over-the-top taunts and insults, but, as the documentary portrays, these comments may not have been without their malicious undertones. File footage of Ali talking about speaking at a KKK meeting, inter-cut with footage of a burning cross, producers a chilling effect. A much quieter, and more natural moment, of Frazier as an old man, watching and commenting on a video of the fight from which the documentary takes its name, is just as powerful–if not more so.

Well worth a look for anyone interested in sports, documentaries or America’s sad history of racial injustice.

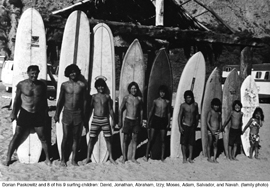

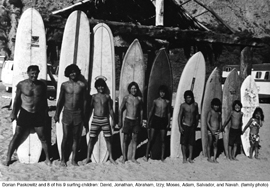

Director Doug Pray on His Documentary Surfwise

Back in 1956, Dr. Dorian Paskowitz—a Stanford graduate—removed himself from regular society. He lived without a mortgage, not tied down to any one place or occupation. He surfed beaches from coast to coast, and then some. However, Paskowitz (nickname of Doc) wasn’t a lonesome drifter. He took his family along for the ride.

With wife Juliette and nine children in tow, the Paskowitzes inhabited a 24-foot camper as they traveled across America. They lived and surfed together and stuck to a strict, healthy diet, and the children were never enrolled in school. For some, this may sound like a sort of utopian existence, but of course, nothing is that simple.

Veteran documentary filmmaker Doug Pray, auteur behind music-themed documentaries Hype! and Scratch, explores the intricacies of the Paskowitz family dynamic in his latest film Surfwise. Not necessarily a surf movie, Surfwise recounts the Paskowitzes’ life on the road and also catches up with the family—now a bit more sedentary—in the present. Pray admits that when he was first approached to make a film about the Paskowitzes, he wasn’t sure if it was a project he’d be interested in doing. But as he got deeper into their story, he became hooked.

“I’m not a surfer,” he says. “I didn’t understand why the film would be interesting, because I first misunderstood that maybe it would just be a tribute to Doc Paskowitz. But as soon as I got into the family dynamics more”¦everything turned around. It’s an incredible story about a family. It’s not even a surf movie, I mean, it is. It’s set in surfing, but it could have been in rock ‘n’ roll or anything. I got hooked on that.”

Surfwise debuted in 2007, and this past Friday, June 20, opened at the Crest Theatre in Sacramento. While wandering through Chinatown in Los Angeles, Pray answered a few of our questions about life with the Paskowitzes.

It seems that the Paskowitzes’ diet—that they weren’t allowed to eat refined sugars and things like that—that Doc was ahead of his time. Nowadays everyone freaks out about refined sugars and flours.

Totally. He is a doctor, and he was way ahead of his time in terms of preventative medicine, the idea of just taking care of yourself, making his kids eat seven grain cereal. Today, everyone’s like, “Sure, you should eat healthy grains.” But this was in the ’60s. There’s very little about Dorian Paskowitz’s medical approaches or philosophies of health that I disagree with. He was dead on the money, and he’s been dead on the money for 40 years. We do eat too much. We’re dying from eating too much, and our society is sick. We do need to eat less, not only because it helps the planet, but just in terms of health. All those things, he’s been in touch with his whole life. What’s interesting, though is that he’s such an extremist, there are so many kids, that enforcing all of that made it really quite dramatic.

Are the kids still following in their father’s footsteps?

It’s kind of mixed. They respect their mom and dad for the most part. Some of them are like, “I wouldn’t trade the experience for anything. We had the best childhood in the world.” And some of them feel as if the movie paints too negative a portrait. But the movie also is very honest about how some of the kids feel that it was wrong that their father didn’t send them to school, and that he was quite an extremist and it wasn’t very easy living in that household, even though they got to surf every day and didn’t have to go to school. It’s interesting, because I think all nine of the kids are sort of conflicted. It’s still a very close family. It’s not like Capturing the Friedmans. It’s not a very dark tale, but it’s very honest. Their recollections are really honest. They’re just a really honest family, and the movie plays both sides of that coin. I try not to decide for the audience. One minute you think, “It’s so cool what he did. What an awesome father. He loved his kids so much that he didn’t want them to get damaged by public school, and he wanted them to eat healthy. He got them in touch with nature and the ocean.” There are so many things that are cool about that that I really respect. It’s just so bold and gutsy to do that. On the other hand, there are other times in the movie where it’s like, “Oh God. I can’t believe it.” There are nine kids crammed into this little camper. They lived really poorly. They never held down a steady job. He pulled them out of society. It was like a little cult or something.

Watching the Webisodes, there were certainly some cultish undertones. Was that something you picked up on?

He’s one of these very charismatic, very dominant, leadership type characters that you run across every so often in life. Many of those people are in leadership positions or do start religions or cults or whatever. And he does have a following. Most surfers who’ve met Dorian Paskowitz think the world of him, and that’s fine. It’s not like they shouldn’t. He promotes healthy living, and he promotes surfing. That part’s all cool, it’s just how far do you go to drag your kids into your trip? Everyone who watches the movie has a slightly different take on that.

I’ve spoke to other documentary filmmakers, and they’ve said that editing is the most important part of the process. Is preserving that sort of ambiguity one of your biggest concerns when working with an editor?

Yes. All my movies, I’ve always said is 90 percent editing. That’s not to take away from the cinematography or the interviews. If you don’t have that, you don’t have anything. But editing is huge in telling the story in a documentary, because you’re presented—in my case—maybe 100 hours of material, and it’s a question of striking a balance. It’s saying, “A movie has to be a journey. Where do we begin the movie and where do we end the movie? What kind of journey is the audience going to go on?” It can tip over at any one moment. There’s a lot of really intense and some funny scenes in the movie, but if it goes too far in any one direction, it can tip over. If the movie focused too much on just Dorian, then all of a sudden we’re missing out on the kids, and the kids are wildly entertaining. To me they’re the heart of the movie.

There are other themes about sexuality, and how you share that with your family, and that could’ve been a bigger theme in the movie. There’s also a lot of talk about religion and Judaism and the Holocaust, and that could’ve tipped it over. It could’ve become a Holocaust movie, which I guarantee would’ve been the first surfing Holocaust movie ever. Not to make light of it, but you know what I mean. We spent almost a year in the editing room balancing it out. It was extremely difficult, but I’m proud of it. My editor did a great job. It’s like writing a novel. You have all this material and you just try to shape it.

The movie premiered in 2007, but another movie of yours, Big Rig, was completed around the same time”¦

Yeah, they’re totally unrelated, but the timing was really”¦very odd. Big Rig was released this month, and it’s all about truck drivers. We’re doing a truck stop tour this summer, and it’s being shown free to truckers all across the country.

Were there shooting conflicts?

[Laughs] I would literally go from a truck stop in Alabama and get on a plane and go to Hawaii. My brain was completely screwed up—truckers and surfers. I must say that they do have some similarities. Surfers are independent-minded people, and so are truckers.

How do you think the Paskowitzes have adapted to life away from the camper?

Well, Dorian and Juliette have lived pretty much the same for 40 years. They’re still very poor. They live a very meager existence. They live in an apartment and Doc makes all his money from selling his books. He still eats totally healthy food and surfs as much as he can. He’s getting up there. He’s like 80 now. He’s in his late 80s and he’s extremely healthy. He doesn’t take any medicine. He lives his life strictly according to his principles, and so does his wife. Their kids are all grown now, so they do [live according to Doc’s principles] to varying degrees as much as they can. I think they’d all like to be as healthy as Doc”¦and so would I, by the way.

I’d read on your Web site that you had never listened to Pearl Jam before making Hype!, and that you’d never scratched a record on a turntable. You’ve already mentioned that you’re not involved with surfing. Do you get influenced after making a film like Surfwise to participate in the culture you’ve been learning about for so long?

A little bit. More of what it does is give me an appreciation for those areas. For the rest of my life, if I run into a truck driver, I can talk to him or her. That’s the thing I love about my job so much. I get to drop into these cultures and meet a lot of people—many of them become my friends and I keep in touch with them long after. I feel kind of spoiled. The downside of it is that I more tell about those cultures and I don’t really live them. It’s more vicarious. I get to observe and meet these people, but I don’t become them because that would be phony. It’s just not me. It’s not the purpose of my movies.