Michaele LeCompte’s Migration of Form is the sum of a lifetime of collecting

The things and people we acquire in life are inherited into our being whether we choose to address it or not. Michaele LeCompte chose to embrace her inheritances and her past through her Migration of Form exhibit, now showing at JayJay Gallery.

LeCompte, a Sacramento City College art instructor and modernist painter, honed her geometric style through years of pursuing various interests and acquiring creative friends along the way. Eventually she obtained the suitable influence required to produce her latest exhibit. Whether it was a friend’s poem, hand-me-down paints or her own past works, she had the intuition to make sense of their significance.

“The most important quality for me as a painter is my subconscious,” she said. “As soon as I make that mark, I think I’m going in one direction, but the painting starts to speak to me and assert itself. It wants to go in a direction I want to fight like crazy. Eventually I have to investigate where I am supposed to go with the painting.”

As an instructor of 26 years she preaches patience in art and her exhibit is living proof. “A favorite image of mine that I share with my students is this artist named Wolfly,” she said. “He was incarcerated in a mental institution and at some point his therapist saw he had talent. From floor to ceiling in his room he had stacks and stacks of work. I always held that in my mind. When you’ve done that many paintings, then maybe something happens. The idea of being patient with yourself is something I always stress.

“There are lots of young artists doing great work already; some of us just have that luck and the gift. They get carried away on a high energy, but for most of us it’s a slower journey.”

Her exhibit is a vibrant depiction of her collected works, spanning decades, collaged into new discoveries and the transformation of poetry into geometric figures. The glaringly obvious first question was how she found the courage to take the scissors to her past work.

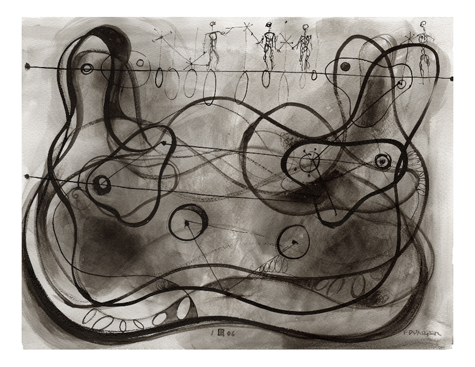

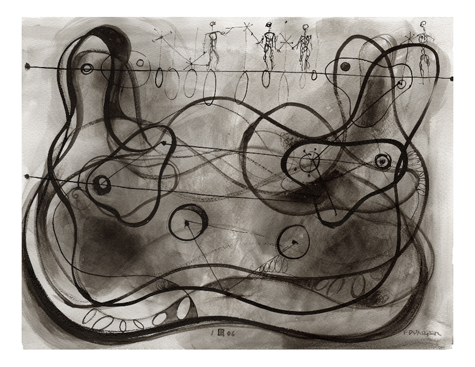

Aerial, 2011

So how did you bring yourself to do it?

Everything you do doesn’t come out the way you think it will or does not hold up to your standards over time. I had a collection of things I felt someday would be a good collage piece. Just this year I had been working on these large paintings and I wanted to have something I could start, put down and walk away from, then come back to.

Was there a specific era you decided was worth using for the collage or is this collected throughout your life?

Some of these pieces have art that goes back all the way to 1975, so there’s little stories in them for me.

Was it difficult to get over the nostalgia for a completed piece from earlier in your life?

Nothing stays the same. What I liked back then does not have anything to do with what I like now, or there will be bits and pieces. So actually it felt like a great weight off my shoulders. To make something from something else that was not working for me and to turn it into something I like better was a neat process. Who knows in 10 more years maybe these will get chopped again.

Looking at these collages, clearly you’ve never had one style. So how did you arrive at the modern geometric forms style that is present in your larger pieces accompanying the collages?

In 2007 I moved into a new studio that didn’t have water. For a very practical reason it made me switch back to oils after many years of acrylics. Plus, I had a friend who had given me a large number of her oil paints…

I didn’t want to use any brush marks. I started using the pallet knife only and that’s how I started the series. My friend Susan is a painter and I asked her how she starts her paintings. She said she starts in the upper left corner and goes to the bottom left corner. It made me laugh so much that I figured if she could do it this way, so could I.

I’ve never been interested in making taped lines. The edge of the pallet knife clogs up and you have to decide if it’s something you can live with or not. Someone was watching me once who was not an artist and he said, “Oh, it’s like you’re frosting a cake,” which is exactly right.

Degrees of Gray, 2010

The piece Degrees of Gray was inspired by the late Quinton Duval’s poem “Oltremarino.” What was it about the poem that spoke to you?

Well, in his poem Quinton uses a quote from another poet, I think it was Robert Hughes, so it’s like we’re all in this line–artists and writers. We have connections and crossovers. But this painting was done so recently after Quinton had died and with the gray pallete, the neutral pallete it was just a perfect thing when I read that poem.

So this is like an artistic time line, in a way?

You can look at it that way. What I aspire to is having my paintings feel like the visual equivalent of what a poem might be. All the parts work, there’s nothing extra. It’s kind of lean and yet it moves you. You get a satisfying, hand-made quality out of these paintings.

Has the overlap of poetry and art always been present in your work?

I’m not making literal connections; I’m not trying for that. I’m not illustrating a poem. There’s a relationship and thread that goes through the work over a long period of time, much the way a poet would rewrite a poem or rework a poem over time.

I got that feeling from your collages. Immediately the words “editing” and “meta” came to mind, which I normally would not associate with art as much as I do with literature.

I’m so bent on working with surfaces that I’ll paint over an old canvas and then you have to deal with the scars that come through from its previous life. I love throwing things together that conflict or press on each other.

Michaele LeCompte’s Migration of Form is showing at the JayJay Gallery now through April 23, 2011. The gallery is located at 5520 Elvas Avenue, Sacramento. For more info, call (916) 453-2999.

Artist Jeffery Felker puts his appreciation for Walt Whitman on Canvas

Literature majors, by nature and necessity, are fixated on written language. Jeffery Felker would appear to be no different. He holds a master’s degree in English literature from Sacramento State, where he also completed his undergraduate studies, and currently works as a part-time adjunct English professor at American River College. It should follow that in his free time, Felker is most likely hunched over a keyboard (perhaps an old manual typewriter, if you’re a romantic), meticulously writing well into the wee hours with designs on authoring the Great American Novel. However, that’s not the case. For Felker, the brush has won out over the pen as his tool of choice in forging his artistic vision.

“I do write, just not that often,” Felker, a Sacramento native, admits. “It’s something more like, hey, I’m in the mood. I’ll do it. But that’s as far as I’ll go with writing.”

Felker earned a minor in art studio while an undergrad at Sacramento State, and it’s served him well. His latest series, The Poetics of Music at Sea, contains 16 pieces (11 paintings and five drawings), and recently opened at the Union Gallery on Sacramento State campus on Oct. 4, 2010. It’s a solo show, and his first at the Union, as well as his first solo show in a couple of years. Felker says he was pleased with the opening, which he estimates drew 60 to 80 patrons–certainly a respectable welcome from his alma mater. However, the humor of debuting his latest series of paintings at the school from which he holds a master’s in literature is not lost on him.

“It was kind of weird,” Felker says. “I got my BA and master’s there, so it was like, ‘Shouldn’t I be coming back for a dissertation on an English thesis?’ It’s kind of ironic, right? I didn’t major in art there, and yet I’m showing there. It was kind of funny.”

While his creative focus is on his visual art, Felker has not abandoned his literary background. The Poetics of Music at Sea is inspired by the writings of the great American poet Walt Whitman. The titles for the pieces in the series were taken from lines from Whitman’s poems. Originally, the series was meant to encompass the work of several different poets, but Felker decided paring the number down to just one would deliver a more “powerful message.”

“It had been a year since I’d actually reinvested time in English and literature, because I was spending so much time prepping for my classes,” Felker says of his decision to focus solely on Whitman’s work for The Poetics of Music at Sea. “I re-found my desire for that kind of literature. I was really digging his stuff. I found so many great quotes, it was like, this guy really spoke to me.”

The Poetics of Music at Sea will show at the Union Gallery now through Nov. 4, 2010. Felker has a couple of group shows on the horizon that will take place in Southern California early 2011–one in Venice and the other in Anaheim, which will have a “circus theme.” He says he’s also planning to co-curate a show with his friend Glenn Arthur from Orange County, Calif. Felker says he has four artists other than himself already lined up and that the show will be “a revitalization of fairy tales” that will take familiar stories re-appropriated by a certain Mouse for mass consumption back to their darker roots. He hopes the show will debut in early 2012. In the following interview, Felker clues Submerge in on his background and the thought process behind his current series of paintings.

The name of your current exhibit is The Poetics of Music at Sea. I thought it was interesting that you used sea imagery in the title, but Sacramento is sort of a landlocked, valley city.

It’s sort of iconic, the sea. There’s a lot of association with the sea in English, at least in my background in English. My concentration was in 19th Century literature. Seafaring was sort of a popular topic in the Victorian era.

The main connection there is with Walt Whitman. The sea is an image, at least for Whitman; water imagery in and of itself is an ode to the power, the birth that water can bring. He was very into earthy things and nature, and he was always commenting on those things in his poetry. I’m kind of concentrating on water as an opposite, as more of a negative.

When did you discover Whitman? Was it through your studies or was he a writer you connected with prior to your time as an English lit major?

I’d heard about Whitman. I’d read a few of his poems, but it wasn’t until my undergrad work, where I was really required to dig into his poetry, that I got really connected to what he was talking about.

Was there a poem in particular that really clicked for you?

Probably “I Sing the Body Electric.” I had to read so much of it, you know what I mean? [Laughs] When you look at Leaves of Grass, there are parts of it that kind of stick out. That’s what I was going with here, too, these specific elements that were speaking to me as far as visually.

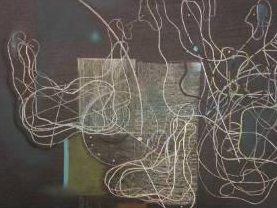

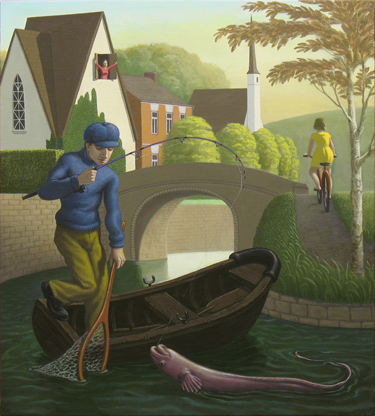

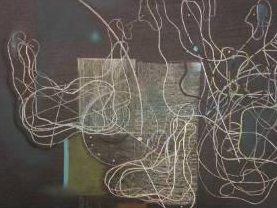

But As For Me, For You, The Irresistible Sea Is To Separate Us, 15” x 19,” Oil On Board, 2010

You said that you’re using water as a sort of negative in this series of paintings, whereas Whitman used water more positively. Is this sort of your rebuttal to his work?

I don’t know if he necessarily always saw it as a positive. There are some poems where the connotation there is not positive–or less than positive–as far as seafaring. But to me, it was interesting to flip that, because I like contrasts and contradictions, so using music as the positive, kind of fending itself off from the seas.

Do you see music and the sea as opposing forces, in a way?

At times, in the work it’s more expressive, where they’re juxtaposed against each other. In other times, it seems like it’s a never-ending struggle.

Looking at some of the paintings in the series, there seemed to be a nostalgic feel to the characters and settings. Was that something you were trying to put forth in the work?

Yeah, definitely. When you look at a lot of the clothing and stuff, it has that Victorian look to it. It’s a time period that influences a lot of the styling and things like that. At least with the clothing–not necessarily the style of the person, concerning hair and things like that, but definitely the clothing is an ode to that. Again, that goes back to reading those 19th Century novels. It’s just a visualizing thing when you’re reading literature from those time periods, that you’re engrossed in not just what the character is going through, but the culture that’s surrounding them. All those images have influenced my work.

Studying literature requires a lot of reading criticism and writing papers. Do you see your paintings as another way of interpreting what you read?

I think so. To me, when I was doing this and connecting Whitman to the imagery, I was like, “Should I be writing a 15-page thesis on this too?” Luckily, I avoided that [laughs]. It’s not like it’s less work or anything, but maybe I’m using Feminist Theory and Historical Theory to get that through and express that through my work. A lot of people who aren’t English majors probably wouldn’t understand that–they probably wouldn’t see that, but it definitely plays a part for sure.

One of the paintings in particular that really stood out to me was I Hear Not the Volumes of Sound Merely. Could you talk a little bit about your process behind that one?

That was the first one that I started working on. I started that one way back in 2009 when I was finishing my master’s degree. I just started with two layers of paint, and then I didn’t touch it for eight months until I finished my degree. I had an idea then of what I wanted to do with the series. It’s kind of weird when you have to put things on hold like that, but that’s how painting is.

When I think of the piano and the movement of sound inside the piano itself, the continuality of vibration throughout the piano–thinking of that, I can see a correlation with that quote. It spoke to me in a way that kind of surpassed music, actually, so it’s almost like the music isn’t enough to contain, just like the emotion that is drawn from that or influenced from that… Maybe that’s a weird quote [laughs].

For more information on Jeffery Felker, check out his website www.studiologica.com.

Artist Jared Konopitski Makes Mixed Things Match

Maybe it’s just a negative stereotype that creative people—you know, musicians, artists and people who go out and get drunk alongside musicians and artists—just aren’t morning people. Artist Jared Konopitski, a Midtown boy, born and raised, was waiting for our phone call at 9 a.m—bright-eyed, bushy tailed and sounding rather chipper. So maybe he is a morning person, or maybe it was the sugar high from the bowl of mango ice cream he’d just eaten. Ice cream for breakfast—he is an artist after all.

Artist is perhaps too narrow a term for Konopitski. Polymath may be more apt. Colored pencils, paints, photography, pencil and ink, Shrinky Dinks (huh?) are just some of the media he’s used during his career. Often, these different media will blend and bleed into one another in Konopitski’s work.

“It’s something that I would say I’ve always done as far as multiple mediums,” he says of his artwork. “They crossover as I learn more mediums. I just get bored, I guess, so then I try to explore, and then I come across something like Shrinky Dinks, and then they come together and it creates all kinds of eclectic work.”

This sort of mixing and matching has made Konopitski’s work not so easy to categorize, even for the artist himself, though he says he tends to lean more toward tattoo culture, cartoon and comic art—and, though he’s a bit loathe to say it, lowbrow culture.

“I think [lowbrow] was a term created by that culture, and in retrospect, they wish they hadn’t come up with that term,” Konopitski says.

Whatever you call it, there’s no denying the charisma of Konopitski’s art. Whether it’s brightly colored illustrations, real-life photographs enhanced with his goofy characters, or the painted Scotch tape sculptures he created in collaboration with Danny Scheible, Konopitski’s work speaks of a limitless imagination and exudes a fun, lighthearted vibe. His latest solo show opens April 2, 2010 at Cuffs Urban Apparel in Midtown. When Submerge spoke with the artist, he was taking a much-needed break from preparing for the exhibition. He says he hopes to have 30 pieces done in time for the show. The works he’ll have on display will be mixed media pieces involving spray paint, vinyl records and Shrinky Dinks. Konopitski says that a few samples of the pieces can be seen on his Facebook page, but he urges those who are curious to check out the exhibit for themselves. We here at Submerge believe you should do the same. It’s a bizarre mixture of materials to be sure, but you know how those artist types are”¦

Are Shrinky Dinks something that you grew up with?

My mom actually introduced them to me. She pulled out her whole antiques there, her charms, and was showing me these little Shrinky Dinks, and I hadn’t heard of them since then.

I didn’t realize they still made them.

I actually ran into a place that was selling blank Shrinky Dinks sheets—just blank sheets like paper. But yeah, I just started making them myself and cutting them out. They’re awesome.

Does the medium you’re working with inform the artwork at all? Does it shape how you create a piece?

Absolutely. Say if I’m working with pen and ink—I don’t know if you’ve seen the tribal works I do—but they become more tedious, more detailed. If I’m working with colored pencils or Shrinky Dinks, they become more cartoonish. I made these sun prints”¦ That’s a whole different technique right there. Those result in creating cutout, silhouette styles and putting them on this paper that’s been chemically laced to react to the sun. So the medium dictates the style I’m going to do.

I saw that you work as a curator also. Is that a big separation for you, working as an artist and working as a curator?

Actually, that’s something I haven’t done frequently, but I have done for a few years. Basically, it’s a thing where I want to see this show, and I want to put this show somewhere, let me find a venue and put this call for art out to all kinds of people and put out a show I want to see, really. It’s like, this kind of show doesn’t exist and I want to see it.

Has working as a curator opened your eyes to how to present your work to other curators?

It helps with networking, I’d say, because then you’re working with other artists, and you’re giving back to them a little. As they find other shows that they’re curating themselves—I’ve found that a lot of artists, once they’ve been showing for so long, they’re also asked to put on shows as well, and they’ll say, “Hey, he gave me a show, why don’t I get him involved too.”

Was it something you went to school for?

I graduated with an AA from the community college, and I was going to move on to the Art Institute, but it seemed at that point that school was going to distract me from what I wanted to do, looking at the students’ work and such. Some of my favorite artists didn’t even go to school. They were all self-taught, so I thought I would save some money and not get all those student loans and try it myself.

We were talking about how the materials you use inspire your artwork. How did working with Shrinky Dinks and records shape your work for this upcoming exhibit?

As far as that goes, it’s kind of a new medium working with acrylic and Shrinky Dink combined. These are the most I’ve done in that way, I guess. They’re all vinyl records, so they’re all circular canvases, and for some reason, I don’t know if it’s because it’s a different shape, but it’s inspired me more than a square canvas. I can’t stop coming up with ideas for it. It’s been a blast. I have more ideas than time.

Has it been a lot of trial and error working with the Shrinky Dinks? I remember when I’d put them in the oven, they’d get all curled up.

This is true. In fact, I didn’t even know that they got so curled up so much at first, so I would take them out of the oven and they’d just be round, curved balls of plastic. I almost gave up, but then I read the instructions, which I don’t do too often, and it actually said to leave them in there longer and they’ll flatten out. I guess that helped out there.

What excites you most about working in the Sacramento art community?

What excites me most is that the artists are so talented. The city is full of talented artists. But what the city doesn’t know, and I didn’t even realize this until I started showing art more, is there aren’t only immensely talented artists, but there are also people who are either traveling through or live here and don’t want people to know that they live here who are big in the art world. There’s folks who have been shown in Juxtapose, High Fructose and those art magazines; there are folks who’ve worked for DC Comics and Marvel Comics, there are folks who know people who make the Cartoon Network shows and Pixar and stuff. I had no idea I’d get to meet these people. I thought I’d show some art in the little town I grew up in, but I had no idea Sacramento secretly harbors these people.

Check out Jared Konopitski’s work at Cuffs Urban Apparel starting April 2, 2010. For more information, go to www.jareko.com or look him up on Facebook at www.facebook.com/ people/Jared-Konopitski/838283475.

Cheri Ibes’ new installation Blank Blank Blank shapes new thought

Cheri Ibes is no stranger to the free-form artistic genre that is known simply as installation. Her work has been locally displayed at Block Gallery where she was the director. In 2008, she opened the gallery with an exhibition in January and closed the year with one in December, both of which were strong, thought provoking shows that received positive attention. Her December show was the end of Block for Ibes.

“Block was an experiment to understand how galleries need to be re-conceptualized and what it might mean for installation and new media artists,” explains Ibes. “How we might develop if we actually had a bit of fertile soil.”

Her new installation might not exactly be the “fertile soil” that Ibes speaks of, but what she’s grown inside of Artifacts in downtown Sacramento is worthy of a blue ribbon. Blank Blank Blank, which opened on Sept. 12 and continues through Oct. 3 is a condensed version of Ibes’ work and shows us a much more linear version of her talent that has not been seen before in her previous work where lamp shades floated like jellyfish and light bulbs were amassed like fish eggs.

Black wooden dowels pieced together in angular shapes touch the wall, leave, and then return only to zig and zag to the floor—ending tangled and awkward. These blank shapes, geometric and strange, cast curious shadows on the stark white walls that they are forcefully fastened to. These shadows create new lines that echo architectural constructs and corners, adding new depth and purpose to the tangled formations that created them in the first place. As I observe Ibes’ installation, a woman brushes lightly up against one of the low sitting conglomerates that consist of ordinary white metal hangars that are fastened together by carefully bound string. The mass quivers and the shadows play, adding a new movement to Ibes’ design.

“I bought all these hangers. I fell in love with these frivolous pristine white forms—their estranged familiarity,” says Ibes.

The movement of her white hangars is poetic. Simply positioned but with such a fervor that it’s hard not to imagine your own distant landscape that they might populate. Her artist statement reads, “Hangars, thin white skeletons, spiny arachnids, scurry from a pole out of an imagined closet like hallucinations from a sick bed or flashes from a forgotten dream. They know nothing—and they know it.”

Blank Blank Blank is her version of this landscape.

In your installations, Blank Blank Blank, you’ve chosen to use objects like light bulbs, parts of pianos, clothes hangars and wooden dowels. Why these objects? What draws you to one particular object over the over? Is it functionality for the piece mainly or is the decision rooted in aesthetics?

I’m attracted to common things with an intrinsic beauty that is often overlooked because of over-familiarity. I imagine that I have never seen these objects before and have no sense of their function. Function corrupts our perception of these objects so we cannot see their beauty—their wonder really. When I broke open light bulbs and computer keyboards and started deconstructing them, I was amazed to find such enchanting things inside as delicate wire filaments and computer keyboards have all kinds of parts inside. I’m attracted to fragility, but fragility with an edge that can seem a bit threatening. That’s an expression of realism—reality isn’t facile, it’s a mixture often of contradictory concepts and that’s what makes them interesting and makes choices so difficult.

Was it a challenge doing the installation in what is essentially a retail store as opposed to gallery space like Block?

Yes, it was. It’s hard to compete with all the things in the background. Part of the reason galleries always have white walls is to clear out the “noise” of other visual and auditory stimuli, so you can really see the work. Also, installation artists, in particular, are very concerned about the space and having control over it. I knew that would be a challenge, but I prefer this kind of honesty of purpose to showing in a gallery that does the same thing—has too much “noise” by showing too many works of art and placing them too close together so they interact with each other and the viewer has a hard time filtering that out.

Do you think your sculptures can only exist in a certain space, with the right lighting? Or can they transform as they are moved from one environment to another? Will they lose their meaning?

Actually, that’s one of the differences between sculpture and installation art. Sculpture is less concerned with space—although space is always important to how an artwork is perceived. It influences it in so many ways. But installation completely bows to the primacy of the environment, of context. Although I might use all the elements in this work again in another space, it will never be the same, and there is absolutely no loyalty to recreating it. It is this recognition of zero stasis that fascinates me about installation. Thus, no, it will not lose its meaning—that is its meaning.

What does the title Blank Blank Blank refer to?

I started thinking about hangers coming out of a closet. Then I saw that the white hanger pieces kind of suggested skeletons, fragile skeleton forms, nerve cells, or plankton, but living. I used that quote from “Canto XIII” by Ezra Pound, a talented insane poetic: “And even I can remember/A day when the historians left blanks in their writings/I mean, for things they didn’t know.“ History has so many secrets, so many folds that we don’t know, or know but don’t really know, or aren’t allowed to know, or are afraid to know, etc. Families and individuals have secrets—blanks in their histories. So I thought of these nervous little skeletal forms as representing the anxiety associated with these secrets and the dowel as representing the closet pole where well-behaved hangers ought to hang. But, secrets are difficult to contain. They have a way of creeping out and creating a subtle underlying anxiety. They are interesting creatures, but they can get tangled in you hair or hook your shirt, so you want to stand a bit back from them.

Your press release reads, “To reconcile the irreconcilable—to find harmony between the careless consumption of urbanism and a natural world subject to human infringement.” Can you elaborate on this a little more? What did you ultimately hope to achieve with this current installation?

People have often commented that my work looks “organic.” I didn’t know what to think about that for a long time. But it kept coming out—just naturally, in all my work. So then, I had to finally accept that it must be pretty important. I had to figure out why I was taking these boring, ordinary man-made objects and they were coming out looking like sea life or microscopic organisms. If it happened once or twice, I guess I wouldn’t have focused on it, but it was always showing up and I never made any conscious effort to make that happen. In my life, I have always tried to figure out how we humans fit into the big picture of nature. I mean we’re temporary, small and probably insignificant in the big picture of nature, which existed before us and will doubtless go on after. Our constructs seem so idiosyncratic and so thoughtlessly placed in the context of nature. It’s an odd fit for the most part. So, I think when I take these rather frivolous human made objects and turn them into organic-appearing organisms, I’m talking about that craziness, that trying to reconcile the irreconcilable—putting our stuff next to nature’s stuff. It’s kind of incongruent.

Where does an idea for a show begin with you? For a sculpture?

I don’t begin with the idea of a show at all. I have these weird useless discarded items I play with. I’m curious about them. I do things to them like burn them or soak them in water or break them apart. I look at them. I move them around. I stack them. I lay them on my bed so their objectivity seeps into my subconscious before I eat my Corn Flakes in the morning. Then I usually begin building them as clusters, colonies. I love how their sameness becomes variation, but in a warped way. They become little individuals. I have boxes of slides from two families’ lifetime collections of their vacations that I am playing with now. Already they look like leaves from a tree—so there it is again—that nature thing. I build modules that can be assembled in an environment like mollusks grow on ocean rocks or mold grows on old fruit.

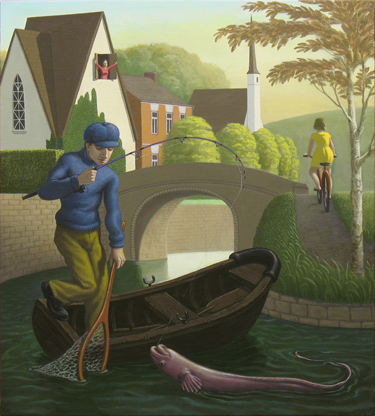

The Invented Worlds of John Tarahteeff

“Most kids draw, but I just kept doing it,” says artist and East Sacramento resident John Tarahteeff of his early forays into art. Tarahteeff has been “just barely” supporting himself as an artist for the past 10 years; however, when he was in college, he decided to channel his creativity toward more practical pursuits. Tarahteeff graduated from U.C. Davis, majoring in landscape architecture and minoring in fine art, in 1994. However, he says that it wasn’t until his life after college that he did most of his studying of painting.

“When I graduated from Davis, I lived with my parents for a couple of years, so that was low rent,” Tarahteeff says. “In school, I was caught up with the landscape architecture studio courses, so I didn’t have much time to do my art stuff. When I graduated, I would just paint all day for like 14 hours a day”¦ After two or three years of doing that, I started to show my work.”

Back then his art did not bear the surrealist bent it does now. Tarahteeff says he experimented with a lot of different ways of painting before settling on the style for which he’s become known.

“There was a whole year there that I wasn’t even painting representationally,” he explains. “I’ve experimented with a lot of different ways to paint and settled into this sort of surreal representation, I guess that’s the best way to put it. And it’s sort of developed, but once I hit on that, I used figures and landscapes and invented worlds, I’ve just kept working in that vein.”

Tarahteeff’s latest collection of works Seaworthy can be seen now through Oct. 3 at the Solomon Dubnick Gallery. In the following interview, Tarahteeff shares his thoughts on interpreting his own work, his feelings about the use of the term “surrealism” to describe it and also sheds some light on his artistic process.

Do you consider yourself a surrealist painter?

I don’t really like that term too much, but I’m not really fighting it anymore. It kind of gets people in the ballpark if I say “surrealism”—the idea of the consciousness coming through. Anyone’s a surrealist anytime they do something. It’s descriptive, but it’s not real descriptive.

Are you a fan of the surrealists?

Yeah, I remember in high school, when [I saw] De Chirico, and his surreal, empty landscapes with the long shadows, I was really struck by that. Even though in humanities, I’d studied more realistic painting, I was like, “Wow, I still like this. It’s kind of abstracted.” I think that was an evolution for me. I think most young people tend to like Rembrandt, like, “Wow, it looks so real.” That was the first time I think that I really liked something not for the virtuosity of the painting, but just because of the mood.

Before you said you tried a lot of different styles. How did you settle on what you’re doing now?

I’d noticed that when I was studying, I was trying to figure out what the essence of painting was for me, like what was important in terms of form. I’ve always had a formal bent to my work—just line, texture, color, tone. What is really important to me? Content, it’s like, what’s important narrative to one person is gibberish to another. So what about form? Maybe there’s a universal thing that’s the essence of what I want to say formally? And so I explored minimalism and abstraction, and representation dropped out. I was trying to get at what can I take away and it’s still a painting to me”¦ I came to the conclusion that I was stripping away everything, and it was almost like I was in my own world and I turned the volume down so low that I could hear what was going on, but it wasn’t communicating to anyone else”¦ So then I just flipped and went in the opposite direction. It was like, take on everything. At first it seemed weird taking on representation—like cartoon-y and everything seemed cliché, but I thought, “Just do it anyway.” And then, as I did it, I found that I really liked it, just coming out of that low volume and all of a sudden incorporating everything that painting could do. Now I tend to gravitate toward paintings that try to do everything, like old master paintings where there’s narrative and abstract qualities in terms of the colors and the composition—just all these levels and symbolism.

A lot of the paintings of yours I saw don’t seem to have much empty space. They’re almost sensory overload.

In some of them, yeah. It’s real dense. There’s something about when the images get dense, there’s an inevitability about them. You can’t really move something without messing something else up. It’s like the painting has to be that way, because everything is so intertwined and interdependent that formally it has a resolution.

In the description of your Picturemaking series that you wrote for the Dubnick Web site, you said that you don’t start a piece of work around a particular theme. If you don’t paint with a theme in mind, where do you begin?

When you called me, I was sketching. I sketch all the time. I’m sketching every day, even if I’m going to paint that day. Usually what I’m drawing is figures in different positions, almost like what a comic artist would draw. After a while, like when I go and revisit the sketches, I go, “Oh, this figure would fit in here.” At first, it’s just fitting these figures together in a sort of puzzle”¦ The process is just making an image for its own sake, and some world emerges. I’ll put the sketches away, and sometimes I’ll see a sketch that I put away maybe two years ago, and I’ll start adding to it again. Eventually, I’ll have something that I’ll try on a canvas. A lot of times, it doesn’t work out at first, and I take something out even on the canvas. Even when I get on to the actual painting, a lot still changes.

Is that difficult to change the composition once you’ve started painting?

Sometimes it goes pretty straight, but most of the time it doesn’t. There are times when I think I’ve got a totally resolved composition, and I go to the canvas and work for a month on it and realize it just isn’t going to work. I’ll save one figure or something that I really like and then just try to rework something else. Sometimes the ghosts of the other figures, like when I’m painting them out, they start to become something else. You start to see other images within it and a whole new painting can come about.

And you’re doing all that without the benefit of Photoshop.

Yeah [laughs]. Just about two years ago, I got turned on to the whole computer thing”¦ I don’t compose with it, but the one way it’s been helpful is that if I think of something like, “Oh what are they wearing,” or, “What instrument are they playing,” and I don’t really know the details, I can go online and just look up “bagpipe,” and I get little bits of information that are real specific that aren’t quite in my memory bank, and it fleshes out the details.

Musical instruments seem to pop up in your work often. Do you play music yourself?

Yeah, I’m in the closet guitarist vein. The only ones who really hear it are my girlfriend and me. And my girlfriend’s a cellist, so I’m learning more about the classical music. I’ve always been more into pop music. But that’s something I’ve noticed, too. Instruments are coming in there more, and I’m not sure what that’s about.

When you look back at older paintings that you’ve done—maybe 10 years ago—do you pick up the symbolism more now than you did when you painted it?

That’s what tends to happen. A lot of times, I can’t even title a piece when it’s done. I have the hardest time, because I need that distance to see what it’s about. I just see all the formal components when it’s more recent. When it’s been done for a while, I just take it on its own terms. I don’t think of it as red over here, or black over there. I just look at as if someone else did it, like, “What does that mean?” I do that with other artists’ works already. I start generating a narrative, even if it’s not what the artist intended, a story inevitably emerges.

For your latest collection at the Dubnick Gallery, is there a narrative in those paintings?

Yeah, I think a lot of times, independently a painting might have a narrative, but what intrigues me is the narrative over the course of my work. That’s the one I’m more interested in”¦ I see characters that recur in my paintings. There are things in my paintings, like a bird”¦and I’ll see that bird in a piece three years later. I know these archetypes in my head have some sort of meaning, and I’m bringing them into each painting. Those archetypes are what I’m interested in, at least as far as narrative. I don’t think in one piece that I ever really get at the narrative that I’m after, but it allows for these archetypes to inhabit these prefabricated worlds. A lot of the genres I take are already out there as far as art history goes. They’re scenes that exist already, and I’m kind of mutating them.

One painting in particular of the new series that I wanted to ask about was The Game; it seemed almost nightmarish. I was wondering what the thought was behind that one.

You know, I don’t know. That one just kind of came out. I’m not sure [laughs]. Yeah, but there’s something. I know that in a lot of my older paintings, I play with the game of desire and seduction. I think it has something to do with that, but I don’t know specifically.

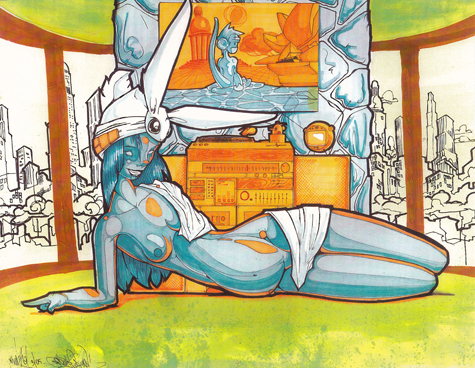

Matthew Michel Hopes His Art Will Make You Worry Free

By Nicole Martinez

“I believe in the year 16000,” says illustrative artist Matthew Michel. It is midday, sunny and warm. He is casually sitting at a table in a small teahouse. There is a buzz of hurried customers around him. In and out the door, people walk with quick steps. Those sitting nearby are all on cell phones, laptops or pacing near the counter waiting for their drinks to-go. Almost everyone seems anxious with serious preoccupied faces.

Then there is Michel. Leaned back in his chair, he is slowly sipping iced tea and tasting honey sticks. He is relaxed, mellow and all smiles. He is 6-foot-2 wearing a madras cabby hat, black vest and jeans. Present and in the moment, Michel is in no rush at all, especially when it comes to creating.

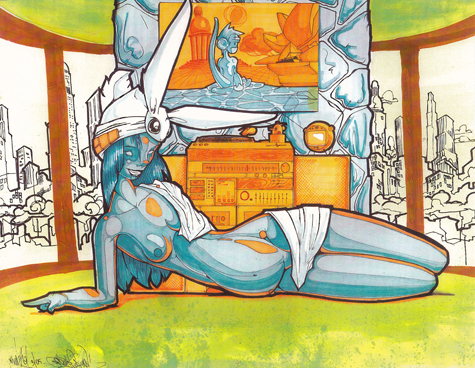

“It’s like the art and music of the past in a futuristic setting where people wear headdresses,” he says describing his pieces. Michel illustrates a post-modern world where elements of the future and the past have merged into a place of relaxation and bliss. Michel imagines that the simple items of today like boom boxes and light bulbs will be relics to treasure in the far, far future. He envisions graffiti throw-ups as huge monumental pieces fixed in stone as unavoidable public art. This of course is juxtaposed with a lovely muse sitting peacefully amid ruins of modern cityscapes and flowers clothed in a flowing robe and giraffe headdress.

“The headdresses are representative of the feelings or personalities of each muse,” Michel says. He uses animal symbolism in much of his work. Giraffes representing regality and elegance, birds as fleeting dreams, pandas can be simple and fish are wise. “It’s like when nature takes back over.”

Contrary to the plain and worn out portfolio in which he carries his prints, each brightly colored ink drawing he shares is a vibrant colorful scene. He uses vivid hues of reds, oranges, yellows and turquoise-blues to capture attention and make certain images stand out. Backgrounds are subtle browns, grays and tans to soften the mood and create a calm, leisurely feel.

“I would like to use my art to encourage people to take it easy,” he says. He offers a visual opportunity for people to leave their current world of stress, schedules, jobs and worries behind and melt away into a state of relaxation. Recently liberated from his job as an accountant for a law firm, Michel is ready to relax and enjoy the small things himself.

“I’d rather look at the lighter side of things, the good side of life,” he professes about himself and his art. Michel wants people to get a sense of “neat-o” when they his work. “I want to illustrate a positive experience, to encourage people to participate, to listen to some music or just enjoy themselves.”

Born and raised in Sacramento, Michel is part of a network of creative people. His mother and father are musicians. Of his two brothers, one is a very precise architect and the other a musician. He himself has always been science and math minded in school but was always sketching and imagining with a pencil in his hand. Working with his family and friends, Michel is part of two art collectives, the Gerald4um, and Revenge of the Cool. Both are collaborative groups of artists, musicians and dancers. Their intent is to bring all sides of art together for people to connect with and just feel good.

“I’ll always be an artist, why not?” says Michel. He can’t help it. “I just want to see what things would look like for the fun of it. Like dinosaurs pushing shopping carts.” He aims to take simple ideas and express them in new ways. He takes pleasure in the world surrounding him and puts it all together, past present and future. With markers and pens he aspires to create the next elevation. Inspired by everything around him he asks, “How can you not do something?” Sitting back again, Michel grins and looks up out the window. “Enjoy the clouds,” he encourages.

Art Brutal

When Submerge caught up with local artist Gale Hart, she was building, of all things, a skateboard ramp in her studio.

“I think I started [skateboarding] when I was 17, 18, when they started building skate parks,” Hart says. “I saw a skate park and said, ‘Oh, I’ve got to learn how to skate.'”

Over the past few years, the 53-year-old artist reports that she has been “really into” skateboarding. While it may not directly affect her art, she does say that the frenetic activity is strangely relaxing.

“It’s one of those things that you have to be completely present while you’re doing it, so it takes me away from any stress,” she explains. “It’s like nothing else I’ve ever done. I’ve bicycled and you can daydream and stuff while you’re bicycling, and it’s not like you have to be consciously alert.”

It may not be what’s expected of a woman in her 50s, but doing what’s expected hasn’t had much sway over Hart through out her life. Just out of high school, she spent much of her time living on the road, in a van, traveling to parks and malls where she would ply her woodcarvings. She recalls, “Back then, malls were really high caliber, a lot different than they are now. It was like a way artists could promote themselves.” But further back than that, Hart remembers realizing her talent for drawing at age 12, though the work she was producing at the time was quite gruesome.

“I started drawing seriously when I was around 12—I mean real morbid, dark stuff,” she says. “Other people started noticing that I had talent, but they had such an aversion to what I was drawing—knives through hearts, daggers through ears and just weird things that pre-teens kind of do.”

Though she says, “I actually don’t think I ever wanted to do anything when I grew up for a living,” Hart eventually settled into her role as an artist, a role that she says comes with great responsibility.

Over the years, she has worked in many mediums—such as photography, sculpture and painting—and has also helped promote the work of others through her gallery A Bitchin’ Space. She has also been curator for shows such as the Circus Art Show, the second installment of which featured live performers, over 100 artists and attracted over 3,000 visitors (including the mayor of Sacramento). She says that experience “kicked her ass,” and now, after a four-year break, Hart has returned to painting. Her latest work can currently be seen at the Solomon Dubnick Gallery as part of The Animal Within exhibit, which will host a Second Saturday reception on Feb. 14, and will be on display through Feb. 28. On very short notice, Hart was kind enough to answer a few of our hastily formulated questions.

5 Points

You were talking about drawing really gruesome images as a pre-teen, and I noticed a link on your site to Artbrut.com, I think. I was wondering if you consider yourself an outsider artist, or if you align yourself with the art brut movement.

Well, with the lowbrow movement, I think things changed in my age. I was doing stuff that’s popular now back when I was a teenager. It didn’t have its day then. Defining myself, I think I’d say I was more self-taught. I’d say that the fact that I didn’t go to an art gallery until I was in my 30s, I guess you could kind of consider me in that genre (outsider art), but I’d go more with self-taught.

A lot of the images I saw of yours were frightening—even the funnier ones. One image from the Why Not Eat Your Pet series features some of the Seven Dwarves surrounding Porky Pig. Are you hoping to shock people who view your artwork?

Well, no, I’m hoping to educate them. I’m hoping that my ability as an artist is interesting enough that people take the time to stop and look at my work because of my skill, and then they’ll get the message.

People are really attached to Warner Brothers and primarily Walt Disney characters. People just have this affection for them, especially my generation and people from their 30s to about their 60s. When you do something with the Walt Disney characters that’s out of the norm, people freak out. They get in your face. And I think, well at least they’re paying attention, but it’s interesting to me because I could take the same content and not use a recognizable character and people will not get the same attention the Disney characters do. I find that really interesting how they care more about the Walt Disney character sometimes than they do with what’s going on in the message and what they’re participating in with their lifestyle.

That’s interesting. I guess people really take those characters to heart.

Yes, I don’t think my intention necessarily is to shock. I think art is a great tool for raising consciousness. I think artists have a responsibility—when they really discover that inside themselves and see what their work evokes in people. Not just, “Oh wow, you’re a great artist,” or, “Oh wow, your technique is good. How do you make those surfaces?” When people come up to me and go, “I really get what you mean,” and, “Oh, man, I didn’t know that happened,” then you just start to be responsible and realize, “I’m really affecting the people who see me.” As an artist, you’re public. I think that comes with a certain amount of responsibility. If you want to really contribute to helping the planet or humankind, I think then, when you know that you can do that, that people will make the right choices as artists, and I did. I just can’t sit around and paint pretty pictures or blow people away with my talent, or all the normal things that the ego drives within art. All of those things are going to remain in my art, but I feel more obligated to talk about how we treat other species.

Bully

The relationship between man and the animal kingdom seems to be a common theme that runs through The Animal Within paintings and your other work. Is it just a hope to educate that draws you to those themes?

How we treat animals reflects who we are as a society, so it’s not just about the animals. It’s about who we are as humans. We’re taking creatures that are so sensitive and so innocent”¦innocent beyond belief. They’ve created no problem in the world other than doing their job, whatever their job might be as the animal they are, and we’re just destroying them and destroying everything else around them. It’s mostly just, “Knock it off.” Come on, people, just knock it off. You have so much power and control. I mean, if someone doesn’t eat an animal, they save a life. The average person eats 83 animals a year. I save 83 lives a year by not eating them. That’s pretty empowering. It’s about raising awareness. If it was about shocking people, I could do that. I could do that to the point where it makes them turn their heads, but I want to invite people into my work and at the same time, I want to put that information out there too.

I wanted to ask you about one specific painting in the exhibit, which also appears on our cover (see below), Forced to Wear Make-up. A lot of the painting is silhouetted, but there’s a small section, an animal’s face, that’s a lot more detailed. Would you mind talking about that piece a bit?

I like that juxtaposition of either pencil and paint, or mixing mediums so maybe they

have a collage element to them. Actually, I don’t really care for collage work that’s done with not an artist’s own work. I like it when artists use collage within the context of their own work.

For that piece, those silhouettes were two people I knew. What I was looking for was something that was super flat, and at the same time, there’s a lot of content and energy in the work too. I like that juxtaposition”¦

Property

Property

Basically, it’s an abstract painting, and that abstract has got a lot of dimension to it. It’s got highs and lows. But then all of a sudden, when it becomes a figure and it becomes the silhouette, it loses all that. You can’t see the depth. I find that as an illusion, kind of, so I’m kind of interested in that. Now mind you, that all this work is experimental. All you’ve seen is all the work I’ve done, and I did that in a month. Basically, Jan. 1 I just started painting. So to talk about it is a little difficult, because it’s new to me, too.

In Forced to Wear Make-up, you have a silhouette of a very violent image, but the background is a very gentle pink. Is that something you planned on when the image was in your head, or is that something that came up while you were painting it?

In everything I do, I try to make the background this really inviting kind of pastel, sweet, soft color. And the movement in the abstract is all dark and dreary or bloody looking. It’s the dichotomy and hypocrisy of us as humans. That’s what some of that intention is with using soft pastel colors with stuff that’s really brutal.

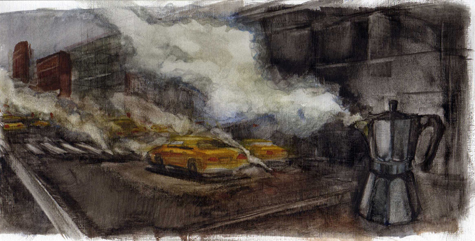

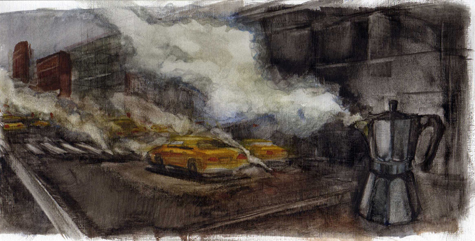

More Real Than Reality

A slice of watermelon, a coffee pot, a steaming train; these things may mean nothing to you, but to the person on your left the same random objects could strike a nerve. In a good way.

When abstract/surreal artist Fernando Duarte had his first Sacramento art showing at The BrickHouse Art Gallery years ago, something extraordinary happened. One Oak Park woman was so touched by one of his paintings on display that she insisted on taking it home that evening. “She just had to take the painting that night,” remembers Duarte of the rare but welcomed occurrence.

“She experienced the same thing I experienced.” Duarte goes on to say, “She later sent me this letter that said, ‘Things happen for a reason.'”

As Duarte carefully pulls the hand-written letter out of a photo album and slowly handed it over he softly said, “That letter to me is more than anything people pay for art. That made me feel like sometimes art really touches people. When that kind of stuff happens, it’s amazing to me.”

Before heading to his current show entitled ABSURDA (an anagram of abstract, surreal and dada) at Inferno Gallery, Duarte graciously took some time out of his Second Saturday afternoon to speak with Submerge in his Midtown studio on topics ranging from “fast food art” to mocking reality.

Were you introduced to art at an early age?

I was born into a family of artists in South America. I am the youngest of seven; four of them are painters and artists. When I was 4 or 5 years old, I used to go to the art school with my brothers. I have no notion of anything else, I don’t know anything about accounting or medicine it was only art in my house. I had no choice; I had to become an artist.

Now that you’re a full-time artist, do you think of it as a regular job the way most people think of their jobs?

Yeah, it’s just like when you’re a monk or something, you cannot be an 8-to-5 monk [laughs]. I try to paint, draw and do prints daily. I go home, I sketch. If I’m at the studio, I sketch. Even if I travel, I sketch.

How did you come to settle in Sacramento after spending so much time in the Bay Area?

When I had kids somebody told me, “Davis is great.” Basically that was the first move years ago, back in ’80-something. I got divorced and moved back to the Bay Area but my kids were here, so they were the main reason to be in this area. Eventually I started working more in Sacramento and knowing more people. And when the economy is so crazy in San Francisco that not even the mayor can pay his own rent, they push you out: From San Francisco to Emeryville and from Emeryville to here. You pay per square foot [for a studio], so I told the guy, “Give me a square foot, I’ll do a 1-foot by 1-foot painting [laughs].” They brought in all the dot-comers and heavy industries. This is what happened everywhere I had been.

Back in ’05 you were quoted saying, “I see a lot of potential in the Midtown area.” Now that it has been a few years, what are your thoughts?

It’s amazing, it’s getting better and better. I think Second Saturday is a little bit cuckoo. It’s becoming what I call “fast food art.” But it’s good; at least it brings people out in the streets. What the people need to learn now is to divide the art, food and music. Sometimes people go into the galleries just like it’s a meat market for the wine and food and that’s it. Art becomes secondary. It still has great potential, though.

Is that why you had the ABSURDA reception before this Second Saturday, to avoid the crowds and the madness?

I did the opening last Friday because tonight I don’t think I will have time for buyers. People came from the Bay Area mostly, along with friends from Davis and friends from here. I like to be with them for one particular day without the whole crowd because I start to lose it. I don’t like openings anyways, but I do it because you have to do it. It becomes like a zoo, you’re like an animal in a cage and they analyze you and check your work. Now what they need to learn is to really understand art. People spend $200 eating sushi but won’t spend $300 on a print that will last forever. It’s an investment for yourself and for your future. Every time I sell something, I invest more than half of it back into art.

So you consider yourself an avid art collector then?

I have over 65 pieces. If I don’t do this stuff, who is going to do it? If you’re a musician, you buy music, you know? If I’m tight on money, I still buy art. It’s important.

I’m curious as to how you would explain your artwork to someone who had never seen it.

In words it’s hard to say. But I would say that it’s just mocking reality a little bit. I try to make a painting more real than reality sometimes, even if it doesn’t exist. I love the metaphysical or surreal point that you fake reality in a way. Reality can be anything but I like to play with the ambiguousness of reality and non-reality. You have to understand I was born in a town in a country where reality was so crazy. You can walk down the middle of the street and see a horse walking by.

When you’re painting are you thinking about how the piece is going to make people feel when they see it? If so, does that affect your work?

Yeah, sometimes when I’m painting I have this brainstorm in my head about everything, except money, honestly. I am even thinking about the person who is going to frame this work. I am thinking about how is it going to be looked at, how would it look upside down? What are the people going to think, what are they going to say? Painters forget about this, they become so involved with the painting, and that’s good but at the same time you have to think, “How are people going to react to this?” I’m not trying to please everyone and I’m not thinking about if it’s going to look good or bad in their living room, or if it’s going to look bad in their office. I don’t care about that. But I do care about feelings.

Skinner Foresees the Fall of Man with His Latest Exhibition

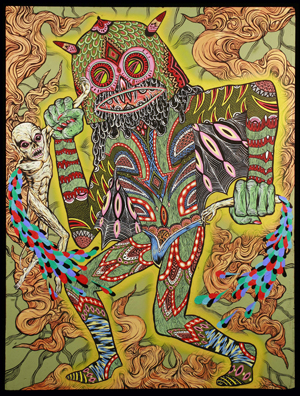

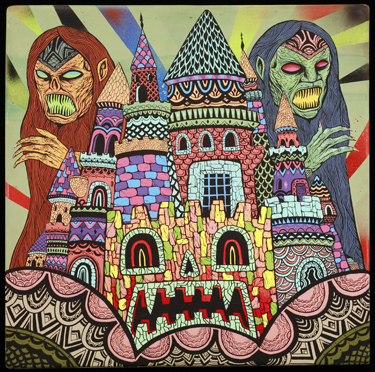

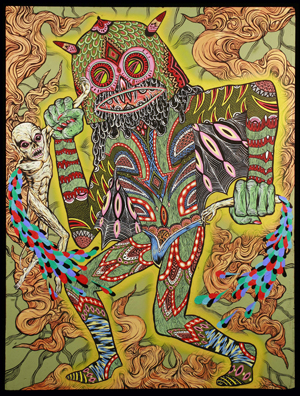

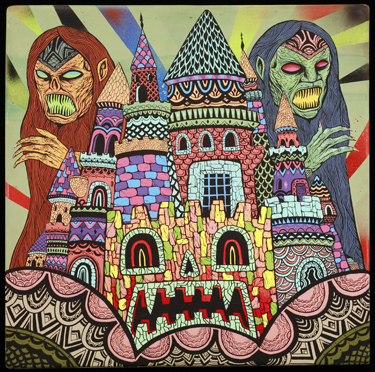

Whether you’re a nerd, stoner or activist, Skinner’s art may speak to you. The Sacramento-based artist has had his work adorn local architecture ranging from the Sacramento City Skate Park to Big Brother Comics, and now with his upcoming show at Upper Playground, entitled No More the World of Man, Skinner hopes to “raise the bar” for himself.

“It’s fun for me to do these insane art shows, and this is the first time I’ve gotten really socio-political and it’s because my mindset is now so affected by the Bush administration and the world beneath that,” says the artist. “I feel like we’re an obnoxious entitled white culture. I think it’s bullshit. I think a lot of things need to be addressed before we can become this evolved, peaceful society of people. And if that doesn’t happen, fuck it. I don’t think there should be any babies for 100 years, and then the animals can have the planet back and everything will be cool.”

In addition to the show’s content, Skinner will also employ a few different techniques to create a more engaging event than simply looking at paintings hung on a wall. The artist has welded life size bodies and swords to adorn the gallery space and 3-D glasses will be available to heighten the viewing experience. He says the glasses work by separating the color spectrums of his paintings causing some colors to appear closer to the eye while others seem further away. The effect is rather trippy.

“I’d probably go to jail for giving everyone LSD-laced Kool-Aid, so I’ll just give them some 3-D glasses,” he jokes.

No More the World of Man opens as part of Second Saturday on July 12 and runs through August at Upper Playground on J Street. In anticipation of the event, Skinner gave Submerge a brief window into his “weird ass brain” during a recent interview.

I’ve heard the term “lowbrow art” used to describe your work, and I was wondering how you felt about that.

See, I think that’s an interesting term. It’s an interesting term, but it can be used in a negative way. It marginalizes the message or the effort of something. When something is considered lowbrow, it marginalizes what it’s capable of doing and what it’s capable of being. I personally think my artwork is fantasy art, even though it’s not traditional oil painting stuff. It’s fantasy art. There’s so many mixtures of influences in my art, but primarily I would say it’s fantasy art with tendencies toward socio-political commentary. I think the term lowbrow art doesn’t necessarily apply to what I’m doing, because I may smoke a lot of weed, but I’m not stupid.

It seems like a condescending term.

Well, it was a direct rebellion from the pretentious fine art movement, which is so fucking lame and boring.

What kind of things politically do you hope to express with your work?

There have always been these struggles in society between the upper class and the lower class. I provoke a lot of those influences in my art. Also, the idea that we are struggling in this society, especially since this is a capitalist society where the people with the money have everything—the conveniences and the luxury—and basically everyone else is making sure that that happens by working very hard for very little pay. There are some gender inequalities and social inequalities that I find to be totally infuriating. I’m trying to provoke some thought with my art without standing on a soapbox.

Since your art features a lot of monsters and other fantasy images, do you think viewers pick up on the messages or is that not something that concerns you?

I think people pick up on whatever they’re going to pick up on in art. A lot of people like looking at a character doing nothing in a painting, and I think that’s fine, but it’s just not for me. I provide the influences and creativity that I’m a part of, or that I see is relevant in my life and put it out there. I feel like even if people aren’t catching on to whatever knowledge I’m trying to kick out there, or whatever thing I’m trying to share, that they see there’s a level of sincerity to it. I’m grateful if anybody can feel that way about what I’m doing.

When I first saw your paintings I picked up on the Dungeons and Dragons influence because I used to play myself. When did you get turned on to D&D?

I was like 15. I just got into it. There was no social pressure; there were no sports. It wasn’t anything fucked up. You could just draw and get weird and eat pizza with your friends and get into something that’s escapism. I think the reason I try to maintain that level of naïveté or innocence in my artwork is because that’s the part of myself that I see that I love in other people. When I see someone who’s hella old or in a business suit or something like, but then there are these little moments when they act like a kid or you can see how they must’ve been like when they were little, that to me is the magical shit right there. How you were and who you were before you were influenced by social pressures and our social structures, which kind of steer you into column A, B or C. I’m just like fuck all that. That shit doesn’t make me happy. Competitive capitalist ideology—I can’t flow with that shit.

Your work is really psychedelic also. When did your fantasy influences start to merge with the more hallucinatory stuff?

I started to research a lot of these Mexican and South American tribes and their usage of psychedelics. I noticed that their awareness of the color spectrum and their ability to use colors to create optical illusions and create a level of intensity that I found very spiritual and strange. I introduced that into my work; a lot of artists now are using low tones and mid-tones, tans and dark greens and stuff, but I just got brighter and brighter. I just like it. It looks really good to me. Plus, I did a lot of acid in high school and I would take a lot of drugs. It was really hard for me to exist with my weird ass brain in Auburn.