Sculptor, installation artist and Sacramento City College professor Mitra Fabian turned an obsession with tape into an enlightened path toward a full-time life in the arts. The answer was on her desk, stuck to her fingers and keeping her chip bags sealed.

Mitra Fabian uses tape a lot and not just in her art. She admitted in one interview that she tapes chip bags shut when she’s finished. In her twenties she subtly incorporated tape into her art, which mostly utilized wood and metal, as an adhesive for hand-made paper, flower petals, leaves and bee’s wax. By graduate school she created an entire thesis on tape. “And not just any tape,” she joked. “But satin finish Scotch tape. No, I don’t get paid to say that.”

If her month-long installation at Bows and Arrows, near 19th and S streets, entitled Signs of Growth, is a continuation of her most recent works, be mindful of the crystal and slime-like growths around the collective. Fabian’s work with tape and office supplies reduces the inanimate to an unrecognizable state and arranges it in a manner that returns it to an organic growth or infestation. She has an uncanny ability to make hardened glue globules look like hatched insect eggs, wound tape becomes icy crystals, and neatly folded blinds look like a giant fungus. She’s listed as a sculptor but could double as a scientist or worse yet, a mad scientist.

“I definitely have apocalyptic, science fiction notions running through my brain,” she said. “As the line between natural and artificial becomes ever more difficult to discern, I dream of new organisms generating from these bizarre marriages.”

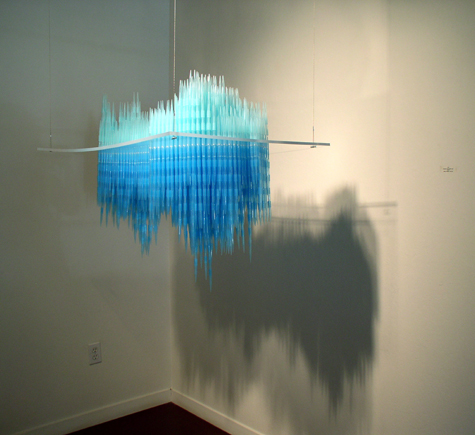

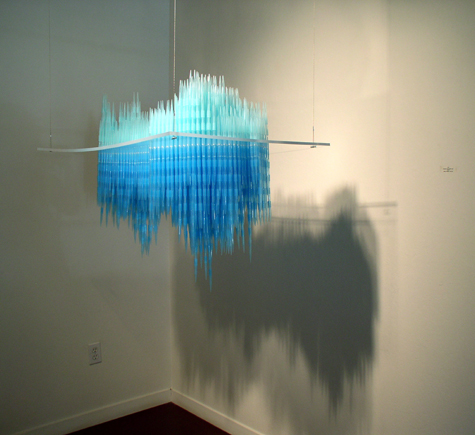

Open-Ended Series II, plastic film, acrylic, glue, 2010

How did you arrive at this format?

At the time I was looking for a material that was translucent with which I could build easily. I tried resin, various kinds of fabric and paper. None of these worked; resin was too time-consuming and toxic, fabric would not hold shape. I wanted something more immediate. And I realized that the answer was right in front of me–something I used and have a strange obsession with–tape! And that is what started the office product trend.

Were you by chance working in an office around these supplies?

Yes, sort of. I worked as a production manager for a furniture company in Los Angeles. Half my day was spent overseeing the people who refinished and upholstered the furniture and the other half was spent at the showroom–behind a desk, processing orders, filing. These systems of order and the products that facilitate the process became a curiosity to me.

As you began tinkering with items, it appears as though your discovery led to a manipulation that renewed the item to its organic state or linked it to something more organic, like crystals or the drip effects in caves. Can you elaborate on these phenomena within your work?

I equate my process to that of child’s play. Not in the sense that it is easy, but rather that I spend time with the material, playing with it. Pulling it, pushing it, taking it apart. I want to discover its limits of manipulation while hoping that it does something interesting. I want it to undergo a transformation; in my own naïve way I am playing scientist. I like the idea of taking something manufactured and forcing it through a metamorphosis to become something that looks natural. I enjoy those kinds of ironies because I am fascinated with the persistence of humans tampering with nature.

5,500 Into the Deep, black tape, 2011-2012

I don’t think many artists find the idea of viewing themselves as scientists all that appealing, since artists are usually pursuing the creative over the concrete. Did you ever want to be a scientist?

When I was young, I did not want to be a scientist. I was not a strong science student, so I never thought I had enough smarts to pursue something like that. But when I think about how I played as a child, I was playing in the mud, creating worlds with natural materials and watching insects with rapt fascination. Now in my adult life I recognize my interest in science, but I still don’t think I have the brains to contend with things like chemistry. I am much happier watching anything David Attenborough hosts! I did study anthropology in college, and my husband is a professor of anthropology and archaeology, so I often feel my social science background definitely plays a role.

I get this feeling like your work is making a statement on humans tampering with nature. What’s your opinion on our role and interference?

I think it’s inevitable and maybe necessary that we tamper. It’s human nature. And I think that very often people are trying to improve upon something. For instance, I recently heard about a genetically modified mosquito that is bred to produce offspring that will die. Considering how I just got eaten alive in rural France for the month of July, I thought, Hooray! That sounds fantastic! But the skeptic in me then thinks, how do we know that this won’t go terribly wrong? That the mosquitoes won’t somehow build up a resistance to it?

Sometimes we tamper to save things, like animals on the endangered species list. But if you think about it, that is kind of a bizarre endeavor. I am usually not of this opinion, but sometimes I wonder if something is meant to go extinct. The repercussions of keeping it around artificially may somehow be worse.

B9, plastic pipette tips, acrylic, 2010

Some of your work has a grotesque or abomination feeling to it, as though the natural is rebelling or in conflict to its surroundings. Is this from our tampering or do you view it as an evolutionary necessity?

Both. I think humans constantly underestimate the intelligence and power of nature. Going back to the mosquito example–how do we know that it won’t over time adapt to circumvent the modification and become more fertile?

Besides the sculptures themselves, the lighting and photography of the piece seems to play a vital role. Would you agree?

Absolutely. I am naturally drawn to materials that emit or reflect light in enticing ways. So ensuring that the light shows off these assets effectively is very important. That makes the photography challenging sometimes. I either hire a professional or spend lots of time correcting in Photoshop.

Is the use of shadow intentional?

The shadow is a direct counterpart to the light, so yes, it does become important. As far as what it conveys… I am not sure. In many cases a sense of drama.

Have you picked up little tricks to gather up a large amount of materials at an economical price? Even free?

I often collaborate with local manufacturers in using their “garbage.” But I also have a few sources that sell these cast-off materials for reasonable prices. And if it’s a household product, I will put the word out, and I will get free donations. At one point, I had all my neighbors setting aside their black plastic.

Whorl III, plastic film, acrylic, glue, LED’s, 2012

Signs of Growth will be on display at Bows and Arrows in Sacramento from Sept. 7 through Oct. 3, 2012. An opening reception will take place from 6 to 9 p.m. on Sept. 7. Check http://www.bowscollective.com/ and to learn more about Mitra Fabian, check out Mitrafabian.com.

Demetris Washington becomes a better man through art

Photo by Edgar Guerra

As a toddler, Demetris Washington used to think of the world as his own personal canvas. He started off as would any other child, scribbling on anything and everything he could grasp with his tiny hands. To his mother’s disadvantage he would create pieces of art on the walls, the floor and sometimes even paper. “When I looked at my ultrasound, I was in my mom’s stomach and there was a pencil right next to me. I had a palette and everything,” Washington joked while eating an oatmeal cookie outside of Sugar Plum Vegan Cafe. “When I came out [of the womb] I had a No. 2 pencil. The doctor was like ‘He’s going to be an artist.’”

In elementary school, Washington began to create comics with his own characters that left his family wondering where his imagination would take him next. “I never had fun drawing other characters. I never drew The Hulk, never drew Superman or anything like that,” he said. “I always came up with my own characters. My uncle was always asking, ‘How do you come up with this stuff?’”

While attending high school in Stockton, Calif., the realization that art can become a career started to settle in after he got paid to paint a mural of the school mascot in the boys’ locker room. “I really hyped the team up with that one. Every time they came in [the locker room] I could see their faces lighting up. And I thought, I really like this reaction I’m getting out of them, this is beautiful. People are happy with what I’m doing and I’m getting paid,” Washington said. And while getting his associate degree in graphic design at The Art Institute in Sacramento, he boldly tangled the worlds of comic books and graffiti to form a unique genre of art that he has righteously claimed as BAMR. “Becoming a Man Righteously. For a minute I was really skeptical about this name but when I began to tell people, ‘My name is BAMR,’ they would look at me weird. And that’s the reaction that I wanted, for people to look at me weird but then I tell them what it means,” Washington said.

From scribbling on the walls as a toddler to attending art school, Washington has found himself working on projects for the Sacramento Kings, where he would paint on jerseys, shoes and billboards to raise money for charities. Now he has his own show, Building Legacies, at the adorable Legacy Boutique in Midtown. His artwork pops out at you because it is full of colorful characters and shapes that are dying to jump from the canvas and come to life. Although he did not want to draw mainstream cartoon characters as a child, he was inspired by one cartoonist, E. C. Segar, the creator of Popeye.

“If you look at my characters’ arms they look like they ate a little bit of spinach before they went out,” he said with a laugh.

One piece, called Head Above Water (pictured last/used on cover), shows a man with most of his body submerged in water except for his head. The piece represents Washington starting off as an artist who can finally breathe after beginning to make a name for himself and get more freelance work, he said. Most of his vibrant art pieces are based on his life experiences and ideas that he comes up with, normally between the hours of midnight and 5 a.m.

“I do the paintings at night because it seems like that’s when the ideas come to me, when I’m supposed to be asleep, when I’m supposed to be dreaming. It’s like I’m awake but dreaming at the same time,” Washington said. “I don’t need drugs, I got enough in my own mind. That’s another reason why I paint, because I have the hopes that everybody sees what I’m seeing, so I don’t feel crazy… I sit there and I’m literally struggling to stay sane. I’m sitting there painting and all these thoughts and ideas going through my head and nobody to share it with except this canvas.”

Washington uses his one-car garage as an art studio, which can no longer fit a car in order to store all of the art supplies. But these days he is feeling a bit “too big for the castle” in the small garage and hopes to move to Los Angeles by the beginning of next year and find a bigger studio to work in. After living in so many California cities, such as Monterey, Oakland, Hayward, and Stockton, he doesn’t like to compare the Sacramento art scene with other cities. “I see it as squeezing the last of the toothpaste. Definitely a beautiful place to do art but maybe not as many opportunities for every artist, for every style,” Washington said. “I feel it’s kind of biased. But I’m here, and Sacramento has been good to me, so I’m thankful for it.” Outside of his small Sacramento garage, the 20-year-old freelance artist and graphic designer makes sure to balance his social and work life by finding time to spend with his two young sons.

“They really are the reason why I do everything that I do. I want make an impact on their lives. I wasn’t able to spend so much time with them, because I was working so hard just to make sure they had what they needed,” Washington said. “And I realized what’s more important is the fact that I’m there for them. They get material things but it’s not going to fill in that void where love belongs. So I had to stop for a second, pause and spend more time with them. You can’t become a man righteously if you have two sons that you’re not there for.” But finding time for his family is evident because inside of his sketchbook, which is filled with his own intricate drawings, there are the occasional scribbles from crayons. Washington proudly pointed out the different art techniques that his 2 and 3-year-old sons have created on the pages from coloring with crayons. Demetris encourages his young sons to be creative and let their imagination take over, just like their father’s. “People look at my work and say, ‘Dude how do you come up with this?’ I was going to ask you the same thing. I don’t know how I come up with it. It’s just there.”

BAMR’s Building Legacies is now showing at Legacy Boutique, 2418 K Street, Sacramento. The exhibit is free and open to the public. For more info, call the boutique at

(916) 706-0481.

On the art of Danny Scheible

Words by Bobby S. Gulshan

In the last few months of 2010, Sacramento’s Second Saturday Art Walk emerged as a hotly contested locus of debate. People wondered out loud if the event had strayed from its original mission; was the benefit to Midtown businesses and artists enough to justify the risks? Because opinions abound on both sides, we will likely not see any significant change to the Second Saturday event any time soon.

One thing, however, stood seemingly beyond contention: the art community is an important and integral part of the Midtown scene and of Sacramento in general. The amount of activity within the visual arts in Sacramento defies the notion that a vibrant art community that generates meaningful and important work can only exist within the major metropolises of New York or Los Angeles. To be sure, those cities remain important cultural centers if for no other reason than the sizes of the markets they inhabit. Yet, as artist and sculptor Danny Scheible tells it, there is something special about making art in Sacramento.

“You meet people here and they want to help you,” he says. “There is a community already there. Having been to bigger cities, it’s very much an exchange, what can this person do for me?” This sense of community, of art as the beginning of a practice of going beyond oneself, or perhaps toward some more complete version of the self, resonates centrally in Scheible’s work.

In sculpture, materiality and spatial context play vital roles in the interaction of the art object and its observer. As Danny and I spoke, he crafted flowers and other more abstract objects from rolls of masking tape. “Tape is something that everyone has in their house or wherever, so it’s something people can immediately identify with,” he says. “But it’s also about taking that everyday object and seeing the aesthetic potential in it.”

This intentional choice represents a movement toward the audience, toward their cultural and social location. With respect to spatial location, Scheible sees the importance not just of the gallery setting but of public space. While it brings with it some level of anxiety (things being damaged, openly criticized) venturing into public space is a further gesture toward the audience. In this case, it is to de-familiarize the everyday and punctuate it with an aesthetic gesture. “I might put a small piece out somewhere and then stand across the street and watch and see how people react, or I may leave things along my walking paths,” he says. Scheible will chronicle reactions, and these impressions further inform his process. In this way he is, as he says, “constantly creating myself as a person through my art.”

Scheible is the self-proclaimed “Art Ambassador of Sacramento.” His primary diplomatic function seems to be to inject into the experiences of his artwork–and thus himself–a dialogue or process by which further discovery can be made. “It’s a spiritual or meditative practice,” he says.

Many of our notions concerning modern sculptural works come from either our experience of sculptural objects in a gallery setting or the placement of sculptures in public places such as parks or commercial centers. These experiences tend to remind us of a kind of critical distance that exists between the object and the observer. In the case of minimalist sculptural works, the movement of the observer is a sort of theatrical gesture, but the object remains mute, having no specific relation to the audience other than its spatial fixedness. Scheible’s entire practice, and indeed process, seeks to reinvigorate this relationship with a certain kind of intimacy. In the works that he has given away, Sheible has encouraged others to produce drawings of his work that may subsequently be used as screen-print images, or alternately as hand drawn images, which again become the subject of his own process, as a sort of perpetual feedback loop. And this is key: The constant dialogue, or even dialectic, that generates the self through the process of offering forth the piece, having it reflected, and then taking that reflection as the starting point for the next iteration of work.

Scheible tells me, “I was born and raised in Curtis Park, and I live here now.” Locality is key to his process. The dialogue with the audience requires an immediacy that his interventions in space reveals. However, I don’t suspect that if Scheible keeps it up for long his bounds will be geographically limited. There exists a crucial point at which his art dares to reach into a universal realm: “An artist isn’t something you are born as, it’s something you make yourself into.” For Sheible, this is as much material and spatial as it is social. As he tells it, his strength lies in getting other artists to work together, to show together, and to promote together. This is a fundamental characteristic of anyone who dares to push the art that they believe in to the fore, and make it geographically and socially relevant.

We could have spent hours talking about the importance of public versus private space, or how hard it is for an artist to fix the damn scooter when it’s wrecked. But I look forward to an upcoming solo show, and the show he is curating, all here in our ever-vibrant Midtown arts scene.

Danny Scheible’s latest solo show at Lauren Salon will have its opening reception during Second Saturday in March (March 12, 2011). Scheible’s curated show will take place at FE Gallery and will also have its opening reception on Second Saturday in March from 6 to 9 p.m.

Artist Jeffery Felker puts his appreciation for Walt Whitman on Canvas

Literature majors, by nature and necessity, are fixated on written language. Jeffery Felker would appear to be no different. He holds a master’s degree in English literature from Sacramento State, where he also completed his undergraduate studies, and currently works as a part-time adjunct English professor at American River College. It should follow that in his free time, Felker is most likely hunched over a keyboard (perhaps an old manual typewriter, if you’re a romantic), meticulously writing well into the wee hours with designs on authoring the Great American Novel. However, that’s not the case. For Felker, the brush has won out over the pen as his tool of choice in forging his artistic vision.

“I do write, just not that often,” Felker, a Sacramento native, admits. “It’s something more like, hey, I’m in the mood. I’ll do it. But that’s as far as I’ll go with writing.”

Felker earned a minor in art studio while an undergrad at Sacramento State, and it’s served him well. His latest series, The Poetics of Music at Sea, contains 16 pieces (11 paintings and five drawings), and recently opened at the Union Gallery on Sacramento State campus on Oct. 4, 2010. It’s a solo show, and his first at the Union, as well as his first solo show in a couple of years. Felker says he was pleased with the opening, which he estimates drew 60 to 80 patrons–certainly a respectable welcome from his alma mater. However, the humor of debuting his latest series of paintings at the school from which he holds a master’s in literature is not lost on him.

“It was kind of weird,” Felker says. “I got my BA and master’s there, so it was like, ‘Shouldn’t I be coming back for a dissertation on an English thesis?’ It’s kind of ironic, right? I didn’t major in art there, and yet I’m showing there. It was kind of funny.”

While his creative focus is on his visual art, Felker has not abandoned his literary background. The Poetics of Music at Sea is inspired by the writings of the great American poet Walt Whitman. The titles for the pieces in the series were taken from lines from Whitman’s poems. Originally, the series was meant to encompass the work of several different poets, but Felker decided paring the number down to just one would deliver a more “powerful message.”

“It had been a year since I’d actually reinvested time in English and literature, because I was spending so much time prepping for my classes,” Felker says of his decision to focus solely on Whitman’s work for The Poetics of Music at Sea. “I re-found my desire for that kind of literature. I was really digging his stuff. I found so many great quotes, it was like, this guy really spoke to me.”

The Poetics of Music at Sea will show at the Union Gallery now through Nov. 4, 2010. Felker has a couple of group shows on the horizon that will take place in Southern California early 2011–one in Venice and the other in Anaheim, which will have a “circus theme.” He says he’s also planning to co-curate a show with his friend Glenn Arthur from Orange County, Calif. Felker says he has four artists other than himself already lined up and that the show will be “a revitalization of fairy tales” that will take familiar stories re-appropriated by a certain Mouse for mass consumption back to their darker roots. He hopes the show will debut in early 2012. In the following interview, Felker clues Submerge in on his background and the thought process behind his current series of paintings.

The name of your current exhibit is The Poetics of Music at Sea. I thought it was interesting that you used sea imagery in the title, but Sacramento is sort of a landlocked, valley city.

It’s sort of iconic, the sea. There’s a lot of association with the sea in English, at least in my background in English. My concentration was in 19th Century literature. Seafaring was sort of a popular topic in the Victorian era.

The main connection there is with Walt Whitman. The sea is an image, at least for Whitman; water imagery in and of itself is an ode to the power, the birth that water can bring. He was very into earthy things and nature, and he was always commenting on those things in his poetry. I’m kind of concentrating on water as an opposite, as more of a negative.

When did you discover Whitman? Was it through your studies or was he a writer you connected with prior to your time as an English lit major?

I’d heard about Whitman. I’d read a few of his poems, but it wasn’t until my undergrad work, where I was really required to dig into his poetry, that I got really connected to what he was talking about.

Was there a poem in particular that really clicked for you?

Probably “I Sing the Body Electric.” I had to read so much of it, you know what I mean? [Laughs] When you look at Leaves of Grass, there are parts of it that kind of stick out. That’s what I was going with here, too, these specific elements that were speaking to me as far as visually.

But As For Me, For You, The Irresistible Sea Is To Separate Us, 15” x 19,” Oil On Board, 2010

You said that you’re using water as a sort of negative in this series of paintings, whereas Whitman used water more positively. Is this sort of your rebuttal to his work?

I don’t know if he necessarily always saw it as a positive. There are some poems where the connotation there is not positive–or less than positive–as far as seafaring. But to me, it was interesting to flip that, because I like contrasts and contradictions, so using music as the positive, kind of fending itself off from the seas.

Do you see music and the sea as opposing forces, in a way?

At times, in the work it’s more expressive, where they’re juxtaposed against each other. In other times, it seems like it’s a never-ending struggle.

Looking at some of the paintings in the series, there seemed to be a nostalgic feel to the characters and settings. Was that something you were trying to put forth in the work?

Yeah, definitely. When you look at a lot of the clothing and stuff, it has that Victorian look to it. It’s a time period that influences a lot of the styling and things like that. At least with the clothing–not necessarily the style of the person, concerning hair and things like that, but definitely the clothing is an ode to that. Again, that goes back to reading those 19th Century novels. It’s just a visualizing thing when you’re reading literature from those time periods, that you’re engrossed in not just what the character is going through, but the culture that’s surrounding them. All those images have influenced my work.

Studying literature requires a lot of reading criticism and writing papers. Do you see your paintings as another way of interpreting what you read?

I think so. To me, when I was doing this and connecting Whitman to the imagery, I was like, “Should I be writing a 15-page thesis on this too?” Luckily, I avoided that [laughs]. It’s not like it’s less work or anything, but maybe I’m using Feminist Theory and Historical Theory to get that through and express that through my work. A lot of people who aren’t English majors probably wouldn’t understand that–they probably wouldn’t see that, but it definitely plays a part for sure.

One of the paintings in particular that really stood out to me was I Hear Not the Volumes of Sound Merely. Could you talk a little bit about your process behind that one?

That was the first one that I started working on. I started that one way back in 2009 when I was finishing my master’s degree. I just started with two layers of paint, and then I didn’t touch it for eight months until I finished my degree. I had an idea then of what I wanted to do with the series. It’s kind of weird when you have to put things on hold like that, but that’s how painting is.

When I think of the piano and the movement of sound inside the piano itself, the continuality of vibration throughout the piano–thinking of that, I can see a correlation with that quote. It spoke to me in a way that kind of surpassed music, actually, so it’s almost like the music isn’t enough to contain, just like the emotion that is drawn from that or influenced from that… Maybe that’s a weird quote [laughs].

For more information on Jeffery Felker, check out his website www.studiologica.com.

Lucky Number 13

There is a certain air of mystery surrounding places off the beaten path. Especially to those of us who live in urban areas, lonely country roads, small towns and backwoods locales—and the people who inhabit them—prey upon our fears and curiosities. Area artist Mark Fox has seen this theme surface in his work in recent years. Born in Sacramento and raised in Elk Grove, Fox now lives in Marysville with his wife. The couple has been there for two years, and Fox has mixed feelings on his new home.

“It’s OK,” he tells Submerge, taking a break from preparing for a few upcoming shows. “I prefer living in cities. I like downtown Sac, because you can walk around, and there are trees. Up here it’s a little different. It’s laid-back country style, I guess.”

The new location has had a noticeable affect on his work, however.

“You get those true characters up here,” Fox explains. “We have my favorite guy up here called Marysville George; he’s really rad. He’s inspiring. He’s all about positivity. I try to base some of my art characters on people I see around here.”

He goes to the say, “Marysville reminds me of Elk Grove like 10, 15 years ago when it was smaller. Now Elk Grove is a little bit bigger, but it has that small town feel. It’s cool though. Everyone knows each other up here [in Marysville].”

Apart from the change in scenery, Fox’s recent preoccupation with “hillbilly, folkish” art stems from the death of his mother around three years ago. His loss led him on a road to self-discovery as he ventured back to Tennessee where he learned about his mother’s Melungeon heritage.

Melungeons are people of mixed ethnic heritage who inhabit the southern Appalachian regions in Tennessee and Virginia.

“They don’t know where they originated from,” Fox says. “They’re considered not fully white, a little bit darker, so treated like African Americans back in they day.”

Fox says that incorporating Melungeon-inspired images into his work is a way of showing respect and a sense of pride for his mother’s ethnicity, especially since the group was often discriminated against and ostracized.

“I try to incorporate that and bring it out because it was such a derogative thing to be called a Melungeon,” he says. “They were considered boogey men.”

Though this phase has lasted a few years, the 34-year-old artist (who now paints full-time) has painted his whole life. The 13th of 14 children, Fox grew up in a religious household and his family didn’t always look favorably upon his art.

“I was diagnosed bi-polar, so ever since I was a kid, I think that’s been my therapy—my way of expressing all the problems I had in my head,” he says. “Recently, when my mom passed away, that added to it. That inspired me to put more meaning into my work.”

Fox points out that, though he incorporates a folk art feeling in his work, he likes to mix it up. Living in Sacramento for so long, Fox also likes to add an “urban aspect” to his painting as well. Also, further perusal of his work reveals his abstract leanings.

“I think a lot of it is how my mood is, how I feel about what I want to get out,” Fox explains. “I did start out more abstract. Artists like [Jean-Michel] Basquiat—that whole abstract expressionist movement, inspired me. I was hella inspired by those guys—just hardly any subject matter, just wild paint, expression.”

Artist 179 Taps into the Diversity of the Emerald City

Seattle-based artist 179 got her start in the art world in 1997 as a graffiti artist. In 2000, she graduated from high school, entered graphic design school and started gravitating more toward fine art. Now the artist finds herself facing what most would consider a good problem—rising notoriety.

“It is exciting, and I’m really hyped about all the work I’m getting and all the exposure,” she says. “But at the same time it’s stressful because, like, ‘What if I’m not good enough? What if I slump?’ It’s the ‘what ifs.’ I get a case of the ‘what ifs.’

In spite of the added stress, 179 reports that she has gone through “a really good inspirational period these last few months.” Local art enthusiasts will have the opportunity to see her recent transformation. March 8, 2008 marked 179 first trip to Sacramento for a Second Saturday. The artist will presented a solo show at UnitedState (1014 24th Street) where she collaborated with local artist Illyanna Maisonet to create a live mural painting. In anticipation of the event, 179 spoke with Submerge about her art, upbringing and frightening sermons delivered in Spanish.

Is the graffiti scene in Seattle pretty active?

It comes in waves. A lot of people travel up here, because we have the trains. We’re close to Portland, we’re close to Vancouver, and so we have people who come and go on their way traveling. There’s a small core of people who paint”¦I think Seattle is such a young city that it’s still developing its identity. A lot of people move away from Seattle—they move to San Francisco, they move to New York. It’s always in a state of flux.

Did you grow up there?

Yeah, I’ve spent the majority of my life in Seattle, but I grew up in a farm, migrant town, a little way out from Seattle—about two hours out. I got the best of country life and the best of city life.

Are your parents immigrants?

My father’s from Mexico, and my mother was born in Seattle, but her family’s from Texas—San Antonio. So, I have the Chicano [side], and my father didn’t really speak that much English, he spoke Spanish.

I noticed a lot of animals in your work. Why do you gravitate toward painting creatures?

I don’t want to necessarily put a face on a painting. When you put a face on a painting, it becomes tangible. It becomes, “Oh, that person is a woman, an Asian woman.” A lot of my women look Asian because I look Asian [laughs]. When you put a face on it, you’re able to give it an identity, but with animals not so much. Animals can be a great many things. They could be your spirit animal, or birds could represent freedom because they can fly. They’re not really subjects, but they can be ideas. And that’s something I really started doing just this year—painting animals. I’m really liking that direction, because the possibilities are endless as far as painting them.

You mentioned that your human characters looked Asian, and I noticed there was an Asian influence in your work.

Yeah, well my family is very multicultural. I have cousins who are Filipino and Mexican, and cousins who are Japanese and Mexican. And so when I came to Seattle from that small city, I had all these different cultures clashing together. I was really confused, because I didn’t understand. When I grew up, I had my father and mother, and they were Mexican, and my sisters were Mexican. We knew white people, and we knew that we didn’t like white people because that dividing line between the farmers and the farmers’ workers. We had those kind of social guidelines. In Seattle, there were all these different kinds of people, and I didn’t know how to categorize them.

When I first saw your work, I thought there were a lot of religious themes, but the more I looked at it, I guess they’re more spiritual themes”¦

I grew up Mexican Catholic, and being Mexican Catholic revolves around fear and forgiveness. So, we’re constantly asking for forgiveness—like going to confession and stuff—and even in a roundabout way, asking the Virgin Mary for forgiveness. Going to church when I was little and having this priest yell at you in Spanish was very frightening [laughs]. It goes with the saying, “Putting the fear of God into you.” I came to Seattle, and it’s kind of the same, but it’s not quite as damning—the church I’m currently a member of. I’m not a practicing member, but I’m still a member of a church [laughs]. Don’t tell my grandma that, though.

A lot of the things that I find in Catholicism I don’t agree with, like the way they treat women. I also don’t think you should have to beg for forgiveness. You are who you are, and you try to the best that you are. I don’t think that being damned to hell because you were born with original sin is any incentive to be good. I think you should do good because you want to do good, not because you’re scared of hell. It is more spiritual because I think your connection to God is more spiritual than something in a book or a priest yelling at you in Spanish.

I take that Catholic iconography, and I make it spiritual, but I’m also kind of making a mockery of it, which my grandparents too terribly like. But they understand. I try to explain that I’m not trying to make fun, I’m just trying to figure it out. If I put a hot dog on a crucifix, I’m sorry. It just happens.

Are your parents supportive of your artwork?

At first they weren’t. At first it was graffiti, and it was vandalizing, and it was criminal, and they couldn’t understand that aspect. When I started doing more art, and I started going to school for design, they got more supportive. Now that I’m doing shows, they’re seeing the rewards of all my hard work. Because, you know, they’re family and their concerned: “Get a job, get married, have kids. You’re 25, why aren’t you working on a career and settling down.” Being Mexican Catholic, I should have five kids by now [laughs]. But they’re seeing it paying off and kind of breaking that mold of what it means to be a Latina these days. I don’t have to follow the same path that my aunties and my mom did.