Community celebrates fine artist Milton 510 Bowens’ 20 years of service to art and education

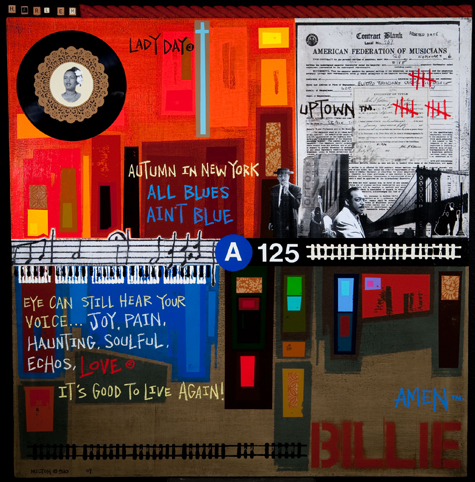

Beatnik Studios on 17th between Broadway and X Street blends harmoniously with Milton 510 Bowens’ latest solo exhibition, Echoes of the Sweetest Sounds.

The former is an urban loft-style gallery made of brick that brings photography, music and local artistry to a shared space. The latter is a well-honored fine artist’s resolve to educate about music, history and social justice through art.

Echoes… celebrates 20 years of Bowens’ work with pieces never before seen in Sacramento and gives a unique spin to this year’s local Black Music Month events (renamed African-American Music Appreciation Month by President Barack Obama).

In the last 20 years, Bowens has reshaped his philosophy as a fine artist and taken the approach of a community activist and documentarian. Since, he has achieved great recognition nationally. Starting in 2009, his art became part of the syllabus for a course study in the Harlem Renaissance at Cornell University’s Africana Studies and Research Center. He is also a spokesperson for the K—8 art immersion program Any Given Child in public schools across the country in conjunction with the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington, D.C.

Bowens has had paintings showcased at the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tenn.; been touted by local newspapers as having the largest solo exhibition (150 large pieces) in the United States in his hometown of Oakland; received this year’s Sacramento Artistic License Award; and received a resolution from the California Legislative Black Caucus for his work on arts and education in public schools.

Undoubtedly, this unconventional exhibition has a message.

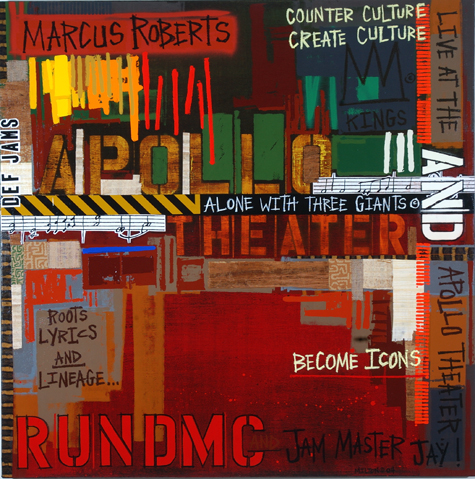

“After you’ve done something for 20 years, it’s hard to choose what to show, but instead of doing a montage of random pieces…I chose those [pertaining to] music,” Bowens says, leaning back and looking relaxed on a sofa at the gallery after grabbing lunch at Slice of Broadway. “Beatnik, jazz, counterculture…it all goes together.”

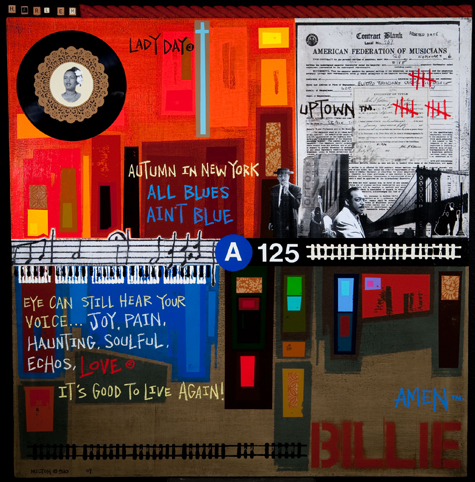

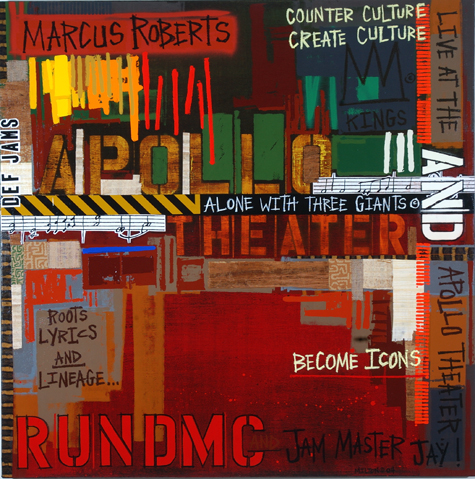

The pieces come from Bowens’ Afro-Classical collection and some from his Soul Music series. He journeys through the jazz era and its historical importance in Afro-Classical with recurring images of everything from records, piano keys and musicians’ portraits to railroad tracks, slave ownership documents and tally marks. On his pieces, he writes what he feels, quotes that he admires and pushes the viewer to take a closer look, “Don’t just hear what the work is saying, listen.”

Bowens mixes media with organic materials like cloth, doilies and prints for “richer depth and more substance.” In pieces like God Bless the Child and Straight No Chaser, the use of children’s building blocks and rope along the top of the canvas adds another three-dimensional element.

“I am trying to poetically encourage people to linger a little bit,” he says of his collages with lyricism that sometimes holds a double meaning.

Bowens says he doesn’t approach his art with a “painterly perspective,” though he has the training and knows the techniques. He attended art schools early on as a high school student in Oakland and later at the California College of the Arts and multiple schools while serving in the Army Special Forces. Two military museums collected and showed his work, and his time in the service helped shape his current philosophy.

“I was in a rapid deployment unit with special forces so I got to travel and see art I’d only ever seen in my textbooks,” he says of the experience. “Seeing it in its original environment was uniquely transforming for me. I was exposed to the fact that there is no magical pixie dust when it comes to art. I learned the definition of art–skill, emotion, spirituality, commitment–and that’s where I’m at today.”

The title Echoes of the Sweetest Sounds originally came up in 1998, Bowens says, when his philosophy and technique changed, and it has become a recurring theme.

Eye Too Am America

“When I listen to music, it’s not just for its commercial appeal,” he says, working up to a more pronounced position in his seat. “There is a poetic standpoint, an emotional response. Quality music to me is like a snapshot of history.”

Take Bowens’ piece Chain Gang for instance, named for a Sam Cooke song. It has photo images of black men in striped garb imposed onto it, as well as a white man with his dogs and gun off to the left, and a worker looking down, holding a hoe to the right.

“I love Sam Cooke’s ‘Chain Gang,’ and when you start to listen to the lyrics, that could be considered one of the first civil rights theme songs,” Bowens says.

The top corner is a bright yellow, followed by bright blue and red. The bright colors sit atop Bowens’ neutral base, like all his pieces, of brown and black to portray not only his urban environment but also to hark back to the Harlem Renaissance, and before that, to slavery.

“The only true colors are what rest on top of the surface, and below that the colors are all muted,” he says. “That’s because when I went to a California museum, or the Oakland Museum…nothing there reflected my Oakland, or my California. In my paintings, you will see the gritty undertone of Oakland, because I grew up seeing concrete buildings and basketball courts.”

Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns largely influenced Bowens’ transformation as well. The artist loved Burns’ idea of taking black and white historical photographs, putting music behind them and then putting the interviews conducted in the documentary in bold color. It was the idea of combining “time, space and history” that enveloped Bowens, so much so that it was all he could do. He even went “cold turkey,” he says, on his other techniques.

Since this change, Bowens says his message is becoming clearer, his work more calculated, his compositions tighter. But the exhibition still shows his reach, including a huge drawing done completely in pencil called Ancient Musicians, a collage of jazz masters and cultural icons that brings Bowens’ collection to a detailed, pictorial climax.

Another influence is Bowens’ family. He gives his mother the credit for helping him reach his career today. Being the youngest of 10 children, and the fifth boy (hence 510), Bowens said his mother could have had less patience with him, but instead she gave the notorious child scribbler scrap paper by having his siblings cut Safeway brown paper bags for him. Bowens incorporates brown paper into his works because of this.

Now, the younger members of Bowens’ family are his biggest influencers.

Autumn In New York

“I have two special goddaughters who help me as an artist see how art can affect young people,” he says.

Bowens works with goddaughter Mizauni, a second-grader, spending time with her as she learns to read and write. She recently won her school-wide reading competition and her family has seen “amazing success” in her educational ability since the two have been spending time together.

“I want to model what I’ve done with Mizauni to help hundreds of children in Sacramento,” Bowens says. Sacramento became the pilot city for Any Given Child, in which Bowens helped place local professional artists in schools to provide an integrated art curriculum and one-on-one interaction with students. Schools in other parts of the state, as well as in Portland, Ore., and Las Vegas, are following suit.

“We take what they are studying, like California history or ancient civilizations, and add art as a teaching mechanism,” Bowens says. “Studies have shown that students have better retention of information this way, instead of just memorization.”

Bowens says he is working toward other projects with youths, including starting a mentor diversion program in Alameda County with the juvenile court system and an art and literacy campaign in Sacramento.

“I’m getting ready to rival [my largest exhibition in Oakland] with the Art of Storytelling exhibition that will engage a program for fine art and literacy, specifically one for third grade literacy,” he says.

Bowens is basing the program off a study that upcoming correctional facilities decide on the number of beds they need by looking at the local third grade reading level.

“It’s not something terrible, it’s just if we see a problem coming, we need to prepare for it,” he says. “We need to get involved now. I’m not a minister… I’m not a counselor, I’m a painter. But I believe I have the skills to make a change and inspire young people to read.”

Some messages like this one are loud and clear in his work, while others take a little longer to see. But that’s the beauty of contemporary fine art, and though Bowens says his art “isn’t to decorate, but to educate,” he adds that he does enjoy seeing it hanging on the walls.

Alone With Three Giants

To catch Echoes of the Sweetest Sounds, visit Beatnik Studios at 2421 17th Street by June 26, 2012.

From clutter, artist James Mullen assembles pieces of grotesque beauty

If you are looking for art that is pretty, don’t expect it from James Mullen. This artist is not out to make art for beauty’s sake.

What is more important to him is to turn heads, in the same fashion that heads turn when people hear the sound of a car wreck, whether they want to see the carnage or not.

If he has caused the observer to ask questions like, “What was he thinking?” or, “What the heck was he up to here?” then consider the piece a success.

“To have a piece that is a bit dark and disturbing is to be that car wreck,” the Sacramento native says. “I’m not looking to hold up an object for admiration; rather, I’m looking to grab someone’s attention, grab them by the lapels and prevent them from looking away, almost to rivet them in place.”

It is appropriate that he should mention rivets, considering his upcoming exhibition, Jagged Edges, at Bows and Arrows, a collection of three-dimensional nail fetish pieces that incorporate wood, nails and doll parts. This body of work, inspired by Congolese nail fetish pieces displayed in the de Young museum in San Francisco, will hopefully make people’s hair stand up, Mullen says, as it is one of his “darker” collections.

A personal favorite is Nail Fetish #8, which is almost Christmas tree-like in a grotesque way. The flayed skin of a doll is wrapped around a triangular piece of wood, a thick spiral of nails curling around it. A telephone rests on the doll’s arm, and in its opposite hand it holds a compass. The piece is whimsical and heavily influenced by Dadaism, Mullen says.

“I find it very powerful and a little disturbing, perhaps, which is what I’m going for,” he adds.

To be clear, Mullen is an abstract assemblage artist. His artistic process is very organic, he explains, in the sense that the objects he starts with will dictate his final product. He may grab one piece from the rafters in his studio, and the rest of the work comes together around it.

Nail Fetish #4

“I don’t know where [the piece] is going or where it’s going to end up, but I just start,” he says. “Starting [gets] the creative juices flowing, and the ideas start moving through my head, and the piece will grow from whatever object just comes to hand.”

As far as what comes to hand, it is an eclectic mix of items that form Mullen’s artistic palette. In this way he is also a collector of odd and interesting things. Animal skulls, for instance, pieces of wood, a rusted bike frame or a horse’s jaw are considered treasures. A goat skull he found on the side of the road was integrated into one of his nail fetish pieces. Often these are objects he finds on the Walker River alongside U.S. Route 395 near his home in Grass Valley, or on bike rides, at garage sales or junk stores.

Nail Fetish #8

Unable to see Mullen’s studio with the naked eye, Submerge asked Mullen to describe his studio in Grass Valley. He did; he also sent pictures of it.

Work surfaces and shelves disappear beneath seas of hand tools, saws, canisters, tubs and boxes. Odds and ends are piled high, while a web of doll heads, cables, tubing and a picture frame hang from the ceiling. This is where he has spent 20 to 30 hours per week creating his nail fetish pieces. From this clutter emerges Mullen’s works of art.

Each work comes together using epoxy, nails, rivets, screws, wire and pressure. The natural tarnishes of the pieces he uses are integral to the characteristic of his work, he explains. In order to preserve the rust and grit of his assemblages, he chooses not to weld, though he knows the skill.

Nail Fetish #2

“I really enjoy the patina of age that items show during a lifetime of wear and weathering and what have you, so I don’t weld,” he says. “I do wear out a lot of drills.”

Assemblage was not always Mullen’s forte. Once upon a time, he worked with clay. In fact he has worked with it on and off for 40 years, since he first began sculpting in high school.

Like a writer becomes afflicted with writer’s block, or an artist walks away from a painting, he too experienced a dry moment sometime in 2007, when he no longer wanted to work with clay. He stopped midway through a sculpture, and for four months did nothing more with it or any other clay works.

Screwdriver Nitelite

Still, he knew he wanted to create art. So, while standing in his backyard, his eyes fell upon piles of rusty fencing, wood and sheet metal, and he decided that these pieces would become his new media. He has been an assemblage artist ever since.

Whoever takes a Mullen piece home has little control over how to display it, because Mullen already has that taken care of. Often he intentionally builds a base into his pieces so he has leverage over the angle it is seen, whether they are built onto pedestals or elevated with wooden chair or table legs. This creates a towering effect.

“Once you make a piece and send it off into the world, you don’t have control anymore on how it’s going to be treated…what people are going to think of it. It’s all out of your hands,” he explains. “But by building the entire piece and including the base, I at least have some influence over the perspective of which it’s viewed.”

Practicality doesn’t always come into play in his pieces, however. As he is largely influenced by the Dada school of thought, his pieces are meant to be illogical and nonsensical.

“I don’t overintellectualize art. I try not to dissect it,” he says.

The Plumbers Daughter

Take one of his older pieces, Plumber’s Daughter, for instance. Plumbing pieces, a section of a steel grill, a doorknob and a lard bucket are arranged vertically atop cherry wooden table legs. There is no rhyme or reason to the bathtub-like creature, except that it was dedicated to Mullen’s wife, who is, in fact, a plumber’s daughter.

While it is a head turner, there is little other meaning behind it. In the same vein as Rube Goldberg, these are little steps to absolutely nothing, he says.

Bows and Arrows will host an opening reception for Jagged Edges on Friday, June 1, 2012 from 6—9 p.m. Find out more at http://bowscollective.com/. You can delve deeper into the mind and art of James Mullen at his website, http://jamesmullenartist.info/.

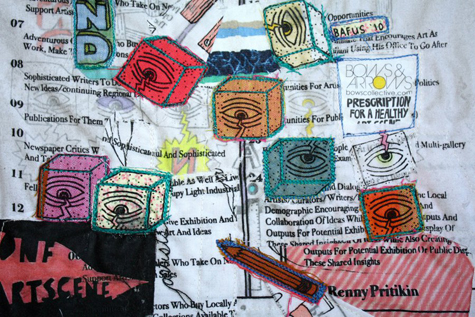

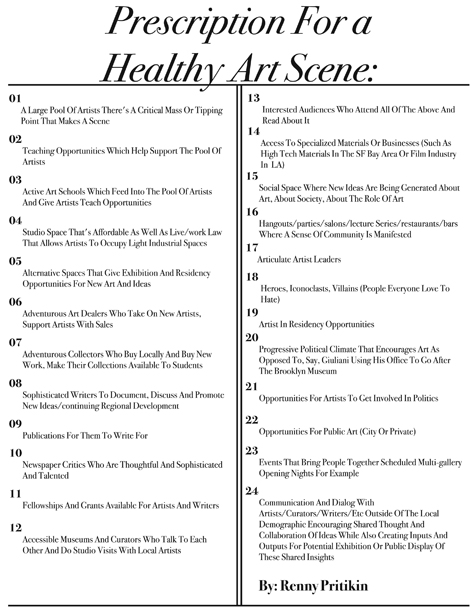

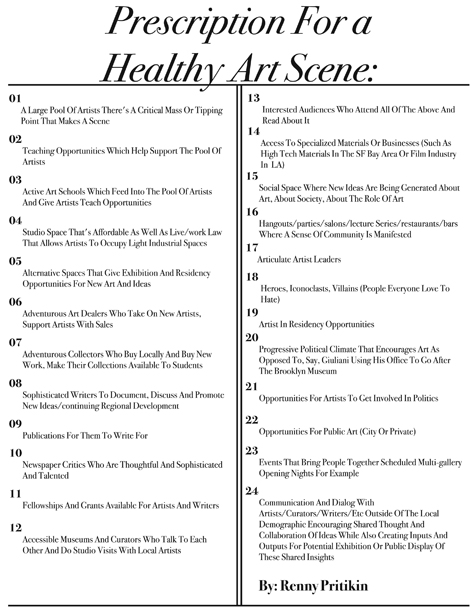

What makes an art scene “healthy?” If you find yourself answering that question with something like, “artists and art galleries, duh!” then Bows & Arrows’ Prescription for a Healthy Art Scene exhibit, opening on Friday, Aug. 5, is sure to expand upon your notion of what makes a thriving arts culture in a community. The exhibit is inspired directly by the writing of Renny Pritikin, director of the Richard L. Nelson Gallery and the Fine Arts Collection at U.C. Davis, who originally penned his “Prescription for a Healthy Art Scene” list many years ago. “I was on a panel years ago, 15 years ago maybe,” remembered Pritikin during a recent conversation with Submerge. “And I can’t even remember what the topic of the panel was, but those were my notes for what I was going to talk about. It’s one of those things where you never know what project that you take on is going to really stick with you and have a life of its own and which ones will just be forgotten. I’ve done exhibitions that I didn’t think much about, that I just threw together and they became famous, you know, and ones that I worked on for years that I thought were incredible that nobody cared about. I’ve written things that I thought were major and other things, like this, that were almost a throwaway but have gone on to have a life of its own.”

Pritikin’s “Prescription” is made up of 24 bullet points ranging from, “No. 1: A large pool of artists, there’s a critical mass or tipping point that makes a scene,” to “No. 8: Sophisticated writers to document, discuss and promote new ideas/continuing regional development,” to “No. 17: Articulate artist leaders,” to “No. 23: Events that bring people together, scheduled multi-gallery opening nights for example.” The list is a sort of Holy Grail for any advocate of local art, including Trisha Rhomberg, co-owner of Bows & Arrows. Rhomberg came across Pritikin’s writings online over a year ago and was immediately touched and inspired by the list. “I saved it to my desktop and I read a bunch of articles online about it and I kept reading it to myself,” she said. “Then I got my sketch book out and wrote the whole thing down by hand so I could start to memorize it and think more about it. Then I was like, ‘Oh my God, wouldn’t it be cool if all my other friends and artists I know could draw a piece of this and we could do a project together?’” And so the idea for the Prescription… art show was born.

Rhomberg collaborated with over 20 local artists, all of whom took items from Pritikin’s list and transferred them onto T-shirts. “Man these shirts are looking cool,” Rhomberg said excitedly. “Every day I’ve wanted to wear one of them. I just want the word out.” One wall inside Bows will feature the Prescription blown up for all to read. The other wall will feature select T-shirts and maybe even some of the artists’ original illustrations framed. Plenty of the shirts will be for sale, too, so not only can you soak up knowledge about what makes an art scene healthy, you can take a piece home with you to wear, spreading the message further and further. After all, that’s the whole point of this thing. “It really is the most important thing I’ve ever come across,” admitted Rhomberg. “And I’m really excited that it has been working. People are working together and learning new crafts and are being supportive and becoming more aware of each other and of each other’s talents and where they live and what they do and participating in buying art, which is what we’ve set out to do.” For more information, visit Bowscollective.com

Toy Sculptor Jay222 follows his gut… and then spills it on his grotesque creations

Following your instincts may sound like the easiest thing in the world to do, unless of course a primal urge is pulling you in an unlikely direction. East Bay toy sculptor Jay222 can certainly relate. Just a handful of years ago, he was enrolled in the Paul Mitchell school, studying hard at the hopes of “working full-force in a salon” as a hair stylist. But a class in special effects/horror movie makeup drastically changed the course of his life.

“That one-day class made me want to put all my focus toward creating monsters instead of doing people’s hair,” he says.

Though his skill at his craft may speak of a life’s work, in reality Jay is relatively new to sculpting. He says he started in 2006, barely five years ago. In fact, fine arts were just something he appreciated in the past. He admits he used to “paint a little bit,” but one day he went down to an art store to pick up some clay and decided to make sculpts of his friends just to see how they would come out and to impress the many visitors to his then home in Daly City, Calif.

Scratchy Seal Robot

“We always had a lot of people over,” Jay says. “I’d constantly come into contact with so many new people, and I just thought it would be dope if the people who lived in the house had their own figures set up on the fireplace.”

The turn in Jay’s path that led him to toy sculpting occurred when he wanted to bestow a fellow artist with a token of his esteem. After getting tattooed by Horitaka, a renowned tattoo artist and owner of State of Grace in San Jose, Calif., Jay made his way to San Francisco to buy him a gift.

“I was loving his tattoo work,” Jay explains. “I was loving what he put on me. He’s such an amazing artist, so I wanted to give him a gift. I went down to Haight Street in San Francisco–Kidrobot–and I came across a tattooed Dunny [“a blank canvas designed to be repainted and reinterpreted by artists from many different backgrounds,” according to the Kidrobot website; it takes its name from its cartoonish rabbit shape] that Huck Gee had made. That was my first exposure to the art toys, and from there, I was just hooked.”

Jay isn’t the first fine artist to make the jump into making art toys. For example, in addition to the work of Gee, a United Kingdom-born illustrator and toy sculptor, Kidrobot’s Dunny series also includes the work of Japanese manga artist Junko Mizuno and Frank Kozik, best known for his iconic rock posters.

“I think a lot of it has to do with nostalgia, but it’s also something you can hold,” Jay says of the fine art toy movement. “You can bring it with you. You can bring it on trips. You’re able to collect them and display them as three-dimensional art pieces in your home or studio. I think that has a lot to do with it.”

Qbert Mixer

Whatever the reason, toys are clearly not just for kids any more. A quick perusal of Jay’s creations is proof of that. On his website, Jay222toy.blogspot.com, Jay has posted videos (one featuring DJ Qbert) of the artist at work. In them, you can see as he turns blank, white, rodent-shaped action figures into grotesque (yet still kind of cute) creatures–the kind that would make George Romero, Sam Raimi or even Italian “Godfather of Gore” Lucio Fulci proud. Jay’s horror-inspired work can also be found here in Sacramento at Dragatomi, which features his splatter-ific Benny Burlap sculpts and the charmingly nauseating Up-Chuck Throw-Up Kids figure. What’s remarkable about these creations isn’t only the vivid and twisted imagination behind them, but also the level of detail. Strangely enough, it’s Jay’s training as a hairdresser that honed is skill in recreating sinew and fascia.

“At [the Paul Mitchell school], they teach you all anatomy,” Jay says. “I studied it during school and kept all the books and kept looking at all the anatomy and kept trying to match the muscle tissue in the books and recreate what it would look like on these characters.”

Jay will bring a whole slew of memorable characters to Dragatomi April 9 with the opening of his latest art show. A tribute to one of his all-time favorite films, Big Trouble in Little China, this will be the first show for which Jay has served as curator. He’s getting off to quite a start, too. Also featured alongside Jay will be notable artists such as local favorite Skinner, Dave Correia, Task One and Alex Pardee.

“I met Alex a couple years back at Wondercon,” Jay says of Pardee. “When I first saw his work, it really blew me away–his detail, his colors, his imagination. He’s brilliant. He’s a genius. His work really caught me, and I’ve always been a big fan. I was really stoked when he said he’d be down for it.”

Jay describes Big Trouble in Little China as a film that has “everything.” Debuting in 1986 and starring Kurt Russell and Kim Cattrall, it’s a story of a truck driver (Russell) who ends up in the thick of an ancient, mystical battle in Chinatown. The action-adventure/comedy was directed by John Carpenter, better known for his horror films such as The Serpent and the Rainbow and the Halloween series (the good one, not the Rob Zombie one).

“It had black magic, sword fight scenes, martial arts, comedy, monsters, creatures,” Jay gushes about Big Trouble in Little China “It had everything that’s awesome about a movie in one movie.”

While his love for the campy classic is clear, would other artists jump on board and share his fervor for the film?

“I wasn’t really sure how it would go over, because I’ve never seen a show that was based on one film,” Jay says. “I’m sure there have been gallery showings that are based on one film, but I wasn’t aware of any, and I wasn’t sure how it would go over with other artists.”

However, Jay stuck with his original idea, and in the end found that others were just as stoked about the project as he was. “It felt right,” he says.

Jay also went with his gut when creating his contribution to the show. He sculpted the Three Storms, characters from the film imbued with the powers of thunder, rain and lightning, which will be available in three different versions thanks to Task One, who helped Jay with the roto-cast resin process.

“I kind of normally stick with my first instincts as to what to make,” Jay says.

And why not? They seem to be serving him well thus far.

Remote Control

Big Trouble in Little China: A Tribute opened at Dragatomi on April 9. A full list of participating artists can be found at Jay222’s website, Jay222toy.blogspot.com. Dragatomi is located at 2317 J Street in Sacramento and online at Dragatomi.com

Michaele LeCompte’s Migration of Form is the sum of a lifetime of collecting

The things and people we acquire in life are inherited into our being whether we choose to address it or not. Michaele LeCompte chose to embrace her inheritances and her past through her Migration of Form exhibit, now showing at JayJay Gallery.

LeCompte, a Sacramento City College art instructor and modernist painter, honed her geometric style through years of pursuing various interests and acquiring creative friends along the way. Eventually she obtained the suitable influence required to produce her latest exhibit. Whether it was a friend’s poem, hand-me-down paints or her own past works, she had the intuition to make sense of their significance.

“The most important quality for me as a painter is my subconscious,” she said. “As soon as I make that mark, I think I’m going in one direction, but the painting starts to speak to me and assert itself. It wants to go in a direction I want to fight like crazy. Eventually I have to investigate where I am supposed to go with the painting.”

As an instructor of 26 years she preaches patience in art and her exhibit is living proof. “A favorite image of mine that I share with my students is this artist named Wolfly,” she said. “He was incarcerated in a mental institution and at some point his therapist saw he had talent. From floor to ceiling in his room he had stacks and stacks of work. I always held that in my mind. When you’ve done that many paintings, then maybe something happens. The idea of being patient with yourself is something I always stress.

“There are lots of young artists doing great work already; some of us just have that luck and the gift. They get carried away on a high energy, but for most of us it’s a slower journey.”

Her exhibit is a vibrant depiction of her collected works, spanning decades, collaged into new discoveries and the transformation of poetry into geometric figures. The glaringly obvious first question was how she found the courage to take the scissors to her past work.

Aerial, 2011

So how did you bring yourself to do it?

Everything you do doesn’t come out the way you think it will or does not hold up to your standards over time. I had a collection of things I felt someday would be a good collage piece. Just this year I had been working on these large paintings and I wanted to have something I could start, put down and walk away from, then come back to.

Was there a specific era you decided was worth using for the collage or is this collected throughout your life?

Some of these pieces have art that goes back all the way to 1975, so there’s little stories in them for me.

Was it difficult to get over the nostalgia for a completed piece from earlier in your life?

Nothing stays the same. What I liked back then does not have anything to do with what I like now, or there will be bits and pieces. So actually it felt like a great weight off my shoulders. To make something from something else that was not working for me and to turn it into something I like better was a neat process. Who knows in 10 more years maybe these will get chopped again.

Looking at these collages, clearly you’ve never had one style. So how did you arrive at the modern geometric forms style that is present in your larger pieces accompanying the collages?

In 2007 I moved into a new studio that didn’t have water. For a very practical reason it made me switch back to oils after many years of acrylics. Plus, I had a friend who had given me a large number of her oil paints…

I didn’t want to use any brush marks. I started using the pallet knife only and that’s how I started the series. My friend Susan is a painter and I asked her how she starts her paintings. She said she starts in the upper left corner and goes to the bottom left corner. It made me laugh so much that I figured if she could do it this way, so could I.

I’ve never been interested in making taped lines. The edge of the pallet knife clogs up and you have to decide if it’s something you can live with or not. Someone was watching me once who was not an artist and he said, “Oh, it’s like you’re frosting a cake,” which is exactly right.

Degrees of Gray, 2010

The piece Degrees of Gray was inspired by the late Quinton Duval’s poem “Oltremarino.” What was it about the poem that spoke to you?

Well, in his poem Quinton uses a quote from another poet, I think it was Robert Hughes, so it’s like we’re all in this line–artists and writers. We have connections and crossovers. But this painting was done so recently after Quinton had died and with the gray pallete, the neutral pallete it was just a perfect thing when I read that poem.

So this is like an artistic time line, in a way?

You can look at it that way. What I aspire to is having my paintings feel like the visual equivalent of what a poem might be. All the parts work, there’s nothing extra. It’s kind of lean and yet it moves you. You get a satisfying, hand-made quality out of these paintings.

Has the overlap of poetry and art always been present in your work?

I’m not making literal connections; I’m not trying for that. I’m not illustrating a poem. There’s a relationship and thread that goes through the work over a long period of time, much the way a poet would rewrite a poem or rework a poem over time.

I got that feeling from your collages. Immediately the words “editing” and “meta” came to mind, which I normally would not associate with art as much as I do with literature.

I’m so bent on working with surfaces that I’ll paint over an old canvas and then you have to deal with the scars that come through from its previous life. I love throwing things together that conflict or press on each other.

Michaele LeCompte’s Migration of Form is showing at the JayJay Gallery now through April 23, 2011. The gallery is located at 5520 Elvas Avenue, Sacramento. For more info, call (916) 453-2999.