Dad’s Sandwiches Celebrates 10 Years…

We’ve been lurking at Sacramento sandwich shops since the Earl of Sandwich was holding it down on 16th among prostitutes and hourly hotels. And though the Earl no longer exists, and one of those godforsaken Goodwill dropoff points has taken its place, there are actually more options for sandos in our great city than ever before. One of those establishments, with an attention to working-class principles and restaurant quality, is Dad’s Sandwiches.

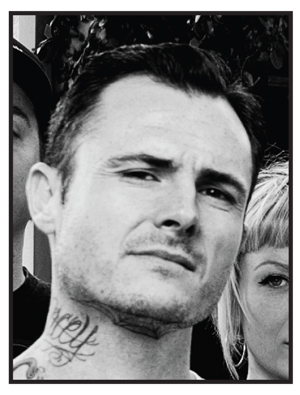

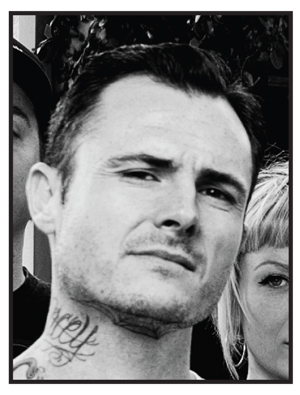

Established in 2004 by a father-and-son duo, Dad’s Sandwiches emerged as one of the premier spots on the south side of downtown. At the time there wasn’t a lot on S Street, and Dad’s success (a combination of blaring rock ‘n’ roll, tattooed sandwich makers and delicious food) allowed them to expand, opening Dad’s Kitchen on Freeport Boulevard. Since then, Rockers DJ Rogers and Mick Stevenson bought the S Street location and opened a second Dad’s Sandwiches on J Street, the 65th and Folsom location was franchised to a longtime worker, and Dad’s Kitchen was sold to unaffiliated investors.

Rogers and Mick Stevenson, aka the “Deli Llama,” helped open the first incarnation of Dad’s Kitchen on Freeport. They met in the kitchen and bonded instantly over sandwiches and metal. “Mick and I,” says Rogers, “we met in the trenches. We bonded, like Ken and Ryu. Dad’s opened in 2004; that’s why we’re celebrating our 10-year [anniversary]. [The previous owner] sold it to us with nothing down, which was nice because that’s all we had. He sold it to us in 2009. And we opened up J Street in 2011.”

“Right when we did buy, it was the start of the downfall of the [economy],” explains Stevenson. “I remember when we were getting to know all these purveyors, they were like, are you guys fucking crazy?”

But Rogers and Stevenson thought of purchasing the S Street establishment as a no-brainer. “No one would hire me,” laughs Rogers, “so it was a simple decision.”

But don’t let simple fool you. The attention to detail reveals more than just a knack for flavorful combinations and fresh ingredients. Dad’s has a consistent menu with occasional changes, which means that their best stuff sticks around to fill your gut. With a recent change of hours at S Street, Dad’s can satisfy the hungry masses for breakfast, lunch and dinner.

To appeal more to the later crowd, they just started serving beer and wine two months ago. The beer list is simple: 24 oz. Pabst, Julian Cider, Lagunitas IPA, Moose Drool Brown and Lone Star—the national beer of Texas. Dad’s is making sure to keep the prices within the working man’s budget, which makes Dad’s my official go-to spot before a concert at Ace of Spades.

“Before when the neighborhood was smaller it was lunch,” says Rogers, who manages the S Street locale. “Now that the neighborhood’s gown up, we’re growing with it.”

Because I had yet to try the breakfast offerings, I recently picked up a Hacienda Hottie at 8:30 a.m. The Hottie, as it is called, was perfect for my spring allergy death match. I was all stuffed up and congested, but as soon as I bit into the bed of eggs, the salty bacon, the rich Jack and cheddar cheeses and the roasted bell peppers and red onions connected with the spicy crunch of the fresh sliced jalapeños, my sinuses cleared right up. That sandwich woke me up, fixed my congestion, and satisfied.

But let’s say you’re more of a traditionalist, a lunchtime sandwich gal. This is where Dad’s shines. I’ve been going there something like quarterly for the last eight years to get a bite, and my default is the Hot Blonde. This toasted beauty is a warm, melted, cool and rich combination of chicken, Swiss cheese and avocado, with onions, spinach and cucumber, layered with garlic spread, mustard and something called pepper plant sauce—which leaves the perfect zing in your mouth, not too spicy, not too bland.

My other staple is the Reuben, which I’d identify as an iconic piece of sandwichness. Dad’s does it right: pastrami, swiss, sauerkraut, brown mustard, house-made thousand island, on toasted organic rye bread. Get extra napkins with this one, and eat it right away while it’s piping hot.

The last piece I want to note is the Angry Roadman. “Angry Roadman sales are slowly picking up downtown,” says Stevenson, who runs the J Street spot. “New people come in all the time. They ask me what to recommend, and I go, I’ve owned this place for five years: Angry Roadman. That says a lot. I eat here every day, and it’s still my favorite sandwich.”

I had to verify his recommendation, and I was happy I did. This hot sando comes with turkey, bacon, roasted red onions, roasted bell peppers, sautéed mushrooms, black olives, tomato and onion with mustard on sourdough. By far this was the highlight of my recent run.

Dad’s has it all: vegetarian, cold, hot, add-ons, chips, delicious beverages, beer, wine and mimosas. They’ve even got a sandwich with walnuts on it.

Yet, while the food is good, it’s the experiences that make Dad’s worthwhile for Rogers and Stevenson. One of the benefits about having a sandwich shop near a rock venue is that they get a lot of perks when they feed touring bands. As Stevenson explains, “I like that the tour managers [when playing Ace of Spades] come to us and trade us [sandwiches for] meet and greets for all the bands that we would pay to see anyways. We met Down, and that was pretty much the greatest day. It was one of the greatest shows I’ve every seen. Seriously. All because of turkey. [The bands] become our repeat customers.”

That music connection is pivotal for Dad’s; most of the employees come from the music scene. When a group of sandwich workers are that passionate about music, there has to be conflicts and fireworks about the legitimacy of certain bands and styles.

Sometimes it even goes beyond the kitchen itself. As Rogers details, “We used to have Sirius satellite radio, and Queensryche would always come on. We had to make a rule: no Queensryche in the deli. If it came on, we had to change the station. Then they were playing at Ace of Spades and we heard they were going to come down here.”

It’s nice that we’re in 2014 and state workers and loud rock can coexist at a sandwich shop. This sort of thing seems inconceivable in the ‘90s. It’s a good sign that the customers don’t complain about the background music.

Rogers explains: “In general they just fucking deal. I know in most restaurants, it would be a sin to play the music we play. It’s not like I play it in the lobby, [it’s in the kitchen]. I’ve got to balance the mental health of everybody back here with the cash flow.”

“In some of our Yelp [reviews],” Stevenson laughs, “they rave about the sandwiches, and then add: Don’t mind the occasional death metal.”

Dad’s just does what they do, and they keep doing it quite well. “If I get someone once,” says Rogers, “I’ve got them forever. I am one with the sandwiches. I know what people want. I have to talk people into what they want. I have to help them out when they’re picky. I’m inside their minds.”

Dad’s Sandwiches can be found at 1310 S St. or 1004 J St. Visit Dadssandwiches.com for hours and more info.

…and the Rockers Who Make Them

Danny Lomeli & Alex Porte

What band(s) have you been in or are you in?

DL: We were in Elysia from 2003 to 2009. Our current band is Summit, and we just put out a new album, Spellbreaker.

How would you describe your sound?

DL: We call it thrash/heavy metal. We are rippers, old-school rippers.

What’s the crustiest thing you’ve done while on tour?

DL: Gatorade bottles are urinals when you’re on the road.

Shann Marriott & Justin Isaacks

What band(s) have you been in or are you in?

JI: I played guitar in a hardcore band called Turn It Around, and we split up in 2008. We did some Canadian and West Coast tours. Played a lot with DJ’s band, Killing the Dream.

How would you describe your sound?

SM: I’m in a slow metal/doom metal band called Church.

What’s the most embarrassing thing you’ve done on stage?

JI: Play guitar poorly—trick people into thinking I am an actual musician.

SM: I wore some denim short shorts at a festival in Tacoma, Wash., where my testicles were shown to the crowd.

Ben Dewey

What band(s) have you been in or are you in?

I play bass for Dcoi. It’s a punk band. We’ve toured the States, toured Europe, toured Canada.

What are European punkers like?

It’s better there. It’s fun. They care more. They care more about the music. They take better care of you. You get paid better. They put you up in hostels, there’s always beds.

Mick Stevenson

What band(s) have you been in or are you in?

I moved here to play with Mynoc. I still currently play with Sans Sobriety and Nevada Backwards, and I did play in Blvd Park.

DJ Rogers

What band(s) have you been in or are you in?

I was in Secret Six, The Ballistics, The Romance of Crime, Five Minute Ride, The Roustabouts, Drugs of Youth and Killing the Dream.

What’s the craziest thing that’s happened to you on tour?

I got detained in a country, and I have no idea where I was. I threw a boulder in a lake, and they detained me. They were talking all about jail time and all these fines. I explained to him, “Man, I traveled all this way to tour this country because I think it’s the most beautiful place on Earth. I admire the culture.” And he let me go. To this day, I have no idea where I was.

Hot Italian co-owners Andrea Lepore and Fabrizio Cercatore reflect on five years in business

On their fifth anniversary, Hot Italian owners Fabrizio Cercatore and Andrea Lepore celebrated simultaneously with Sacramento Beer Week. Hot Italian, as many who have frequented its immense, black and white dining room must by this point know, is the combination of modernist, Italian aesthetic and locally sourced, Californian quality. It is the Old World delicacy made modern in the best state of the West. It is fitting, therefore, that for Beer Week, Hot Italian brought in Birra Peroni from Italy and Sierra Nevada Brewing Company from Northern California, and showcased their pizza-centric acumen with local cheeses and The Center for Land Based Learning, a non-profit that focuses on educating and growing the next generation of farmers here in the Sacramento Valley.

Hot Italian wants to pay homage to its longstanding love affair with the two Mediterranean climates, one seaside, one landlocked. Cercatore learned the restaurant trade in La Spezia, a small province on the west side of the Italian peninsula. As the owner of a restaurant and bed and breakfast, he came to realize his love of cooking all things Italian, but most importantly pizza.

In the early aughts, Cercatore met Andrea Lepore, a second-generation Italian-American ready to make a leap from sports business into the restaurant industry, and together they decided to give Sacramento something it had largely been missing—straight, simple, Italian pizza.

In building their new restaurant, Cercatore and Lepore caught the rising wave of green construction and design. They fused this together with the renovation of a longstanding retail and warehouse space. The building was gutted, and the new pieces were fitted together with a conscious decision to minimize the restaurant’s carbon footprint. At the time, Hot Italian was celebrated as one of the first LEED businesses in Sacramento.

While the New York Times has since canceled its Green Business blog, and the ambitions of a green business revolution have been checked by economic turbulence and the “realities” of international trade, the owners of Hot Italian continue to think green. Their tradition of thinking locally first is evident in their recent Responsible Epicurean and Agricultural Leadership (REAL) certification, a national initiative that looks to promote quality ingredients that are locally sourced, fair trade and non-GMO. The idea is, if the stuff we put into our food is healthy, we should be healthy too. This premise, as Cercatore and Lepore highlight, is the basis for the quality of Hot Italian’s eats, and had been long before national certifications started encouraging food businesses to consider their customers’ well beings before the bottom line.

In short, Hot Italian has been filling the bellies of its patrons, in both Sacramento and Emeryville, Calif., for the last few years. The pizza, salads, and calzones are as simple as the business plan itself: Do something consistently and well while utilizing the plethora of local ingredients available to our region. If the crowds over the weekend are any indicator—the lunch service was still packed at 2 p.m.—Cercatore and Lepore are doing simple, and doing it quite well.

Tell me about your first experience here in Sacramento. What did you think of the city?

Fabrizio Cercatore: I was stuck for six days in Elk Grove, in August, and I tried to walk. I almost died.

Andrea Lepore: I took him to Midtown immediately. There’s things to do here!

Tell us about the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) Certificate. Why did you decide to go green when you were building the restaurant?

AL: We were the first LEED restaurant. There were other buildings, but they were government buildings. It was the first public building that was LEED certified, that you could just walk into…This was a cold shell. It was retail and a warehouse. Basically everything was new: new storefront, new roof, new plumbing, new electrical, new sidewalks. When you have to do that much work, you might as well build it green if you’re going to rebuild something.

Why did you decide on a modernist design?

AL: When we designed this place in 2007, even when we traveled, there weren’t many Italian places that were modern. A few in LA, a handful in New York. We want to celebrate Italian design. We’ve paired that with local Californian design. Mike Wilson, who’s a local furniture maker, has built a lot of the furniture pieces here. I think it’s an intelligent way to design. It’s very functional. It’s not ornate like French Country. Good modern design is designed to be functional. We wanted this place to be warm. A lot of people think of modern as steel and hard edges. We wanted to combine elements.

FC: I like modern design for its simplicity. I like when modern is combined with the natural elements: wood, iron, stone, marble.

Tell me about the REAL certification.

FC: Technically, we didn’t do anything. They showed up, and said, “You need to do that.” And we said, “We already have that, have that, have that.” It was really simple. It helps that we have a lot of combinations with vegetables and pizza. It’s one of their points: eat more vegetables. It helps that we’re in California.

AL: They send a nutritionist and a certification person to the restaurant and check how you source your ingredients. They make sure that things aren’t processed, that the ingredients are local, sustainable, that there aren’t GMOs…If people aren’t buying local here, then where are they buying from? I was in Boston; I went to the market, and it was all stuff from California. We are, I guess, the farm-to-fork capital.

Why has Hot Italian been so successful? How have you made it to your five-year anniversary?

AL: It’s a simple concept. The quality has been there since day one. We’re not gonna do pasta, or osso buco, or have a huge menu. If you want pizza, we want you to come here.

FC: I think people really like the consistency and the quality. The quality is in the food and in the brand. In the beginning the quality might look expensive, but it’s in the meal. We had a new kind of pizza here, in Sacramento. People were used to really thick crust and a lot of cheese. It was more about quantity and not about quality. People responded well [to our pizza]. We have a smart customer.

What we do is real Italian style. There’s a lot of pizza around, but we keep the Italian way. Not a lot of chicken or pineapple. If you want to experience real Italian pizza, you can come here [to Hot Italian] or you can buy a plane flight and go 11 hours that way [pointing east].

AL: It’s a lot cheaper, eating here.

Some restaurants only care about good food, others care about ambiance. What’s the focus for Hot Italian?

FC: We want to give an experience to the customer. The experience is not just in the food but it’s also in the environment. That’s why we have the modern look. When you talk about an Italian restaurant it’s the old Tuscany style, with the red and white table cloths.

AL: We really wanted it to be just like in Italy, a community gathering place, where people come and have an espresso, or stay and meet friends. We wanted to have that same feel. With pizza being such a communal food, it’s the sort of perfect platform for this concept.

What’s your best memory from the last five years?

FC: Before we opened there was a lot of work we did to raise money, when Hot Italian was just an idea. I remember I was putting together events and making everything at Andrea’s house, preparing all the ingredients. Then going to investors’ houses and making pizza in their own ovens. It was crazy. They were like, “How did you make that in my house?” The moment we opened, people understood it, Hot Italian and the concept.

One time we did this big event at the airport. Our first big event as Hot Italian. We made 100 pizzas. We didn’t have enough refrigeration. I was trying to figure out where to store the dough. We had to ask our friends, neighbors.

AL: Bella Bru actually stored the dough for us in their large walk-in.

What’s the big difference between Italy and the United States?

FC: Weeks ago, two of my good friends came to visit me from Italy. I hadn’t seen them in so long, and they stayed for three weeks. They reminded me how my life was in Italy. We were laughing all day, sometimes about stupid things, but we were laughing all day. We were happy, you know. Enjoying the little things of daily life, and I’ve kind of lost that. It’s a different way, easy to get lost in. You forget about that. They reminded me that I’m Italian.

We have a lot of defects in Italy; we are a mess, a beautiful mess. We have nothing. But we have food, we have the family, we have each other and then there’s the next day.

If you haven’t visited Hot Italian in the past five years, where the heck have you been? It’s located at 1627 16th Street in Sacramento.

Julie Heffernan on her process, self-portraits and the reclining nude

1814—Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres finishes La Grande Odalisque, a work that becomes iconic for multiple reasons from various critical perspectives. It’s Orientalism at its finest or worst, an example of neoclassicism betraying reality, an introduction to the gendered gaze and a document of patriarchy’s ridiculous ideas about female bodies as objects and their lack of agency. These ideas might seem current, because they are; but the work, the painting itself, is now two centuries old.

And yet, one of the first paintings one is likely to see at Julie Heffernan’s current exhibit at the Crocker Art Museum is her work Self-Portrait with Talking Stones, and immediately it’s impossible not to see the intertextual play between the Ingres work and Heffernan’s central figure.

In both works we encounter the female nude in an elaborate framework, one lush in figurative wealth, the other a wealth of figurative detail. While the Ingres work is a perfect distillation of patriarchy, Heffernan’s Talking Stones is a critique of not only the elements of Ingres but also the dominant forms and aesthetics that have been derivative of and since Odalisque.

“She is the closest to a reclining nude that I’ve ever done,” says Heffernan. “As I’ve said before, I’ve got a real problem with the reclining nude. How do you give the female agency when you take the vertical stance from her and have her sit or recline. I wanted to have her body speak.”

In Heffernan’s framework, the nude is challenging her placement in the work. She’s placed upon a series of stones that serve as historical reminders Greco-Roman, spiritual or otherwise. These stones become the divan upon which the nude rests. The “exotic” peacock feathers of the duster in Odalisque become a maternal mound of dead birds and fruits heaped upon or emerging from the nude’s genital region. It’s not ripe, as we might think of the precision, delicacy of the still life form, its various bowls overflowing with fruit and remnants of rural continental labor. Rather, this is both abundance and loss, a bounty of sweet over-ripe stone fruits and the end of a sexuality rooted in reproduction—specifically for Heffernan, hers.

{Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ La Grande Odalisque}

These adornments are important to Heffernan. They—these dead birds, wasted fruit—are anything but arbitrary, as they repeatedly appear in various ways throughout her work. Yet, the unique thing about Heffernan’s paintings is that the macro, which seems so important at first, isn’t exactly the takeaway. Instead it’s the little things that give her works weight.

The minute details, the micro of Heffernan’s works, often become the most rewarding parts of her paintings. In person, it’s not the nude figure that weighs on the viewer. Instead, it’s the man fighting a grizzly bear in the right distance; the evangelical, ghostly figures praising what appears to be a wine bottle just below the fight but in the foreground of the large tree that anchors the right side of the frame; the person in a full-body cast and hospital bed further to the right; the miniature man about the size of one of the dead game-birds mentioned above, climbing into, or mounting perhaps, the iron-railed bed next to the pelvis of the nude, birds, fruits and all; the ship ablaze just left of center of the canvas, floating down a river that has also inundated a series of buildings from which no living people emerge; or lastly the peaceful serene sky that floats behind the nude’s head, a stark contrast to all the death, danger, tension, violence and history visible at every other point of this painting.

{Self-Portrait Moving Out | Year: 2010 | Medium: Oil on canvas | Dimensions: 54 x 78 inches}

Despite all this, the nude, the figure, the face of what can only be understood as a projection of Heffernan herself, gazes back at us, the viewers. She’s calm, confident, powerful—despite her placement, slightly reclined, in the work. This look too asks us to confront, as viewers, our desire to see, voyeuristically, trauma and tragedy in the artwork itself, in Heffernan as an artist, in her self-portrait.

“The title ‘Self-Portrait’ started when I kind of rejected any human figure in my work,” explains Heffernan. “This was way back in the ‘80s. There was the whole discourse about the male gaze and the objectified female nude, all those problematics were clear to me. The feminist writings, like Laura Mulvey’s “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” they really hit me, they opened my eyes. It was clear for a while that the nude, the female nude, had to rest. But I still wanted to paint about my own female experience. That was when I moved to these large-scale still-lifes, and I used them as backdrops for the image streaming process that I had been experiencing, where pictures would flood into my head.”

Heffernan describes her artistic process as a sort of prayer, though she denies any particular religious affiliations even if they do appear from time to time in her paintings. When beginning a new work, she sits and waits, for days on occasion, until she finds an aperture which allows her to begin a work. Often this initial impulse is discarded, but it inevitably leads to the actual subject or content she will spend the next two months bringing to life. Sometimes this process takes years, and the negotiation between the large central figures and the minute background details are the delicate elements that Heffernan has to balance.

{Self-Portrait Holding Up | Year: 2010 | Medium: Oil on canvas | Dimension: 68 x 66 inches}

Once she’s comfortable with the larger setup, she begins to develop the smaller aspects of the works. This she calls the “culture” of the painting.

“At a later stage,” she explains, “I know the world and now I want to give it culture. I’ve built the buildings, I’ve laid out the thoroughfares, and then I want to start to parse the fine points of this world, the culture of this world. That’s the point where the intellect gets engaged. It has to do with scanning broadly. I’ll leaf through tons of books and wait for things to pop out as relevant to the world. Sometimes they’re in textual form, and sometimes they’re in image form.”

This act of discovery, of reference, Heffernan describes repeatedly as a journey of sorts. As an artist she attempts to enter the canvas through the paradoxical application of layered paints:

“I’m always trying to go into a hole; the canvas proper, the canvas parameter is the initial hole, a white hole. You enter that, and I’m always adding, trying to cut into deep space, cut into it even deeper.

“I deal with everything from the experience of being a maker. The joy of losing yourself in the tiny muscle movement of hands of creating something is really the best, the only escape we have from our horrors.”

These horrors are both real and imagined, as one can see in her works, actual tensions and fantastic circumstances. Because the works are so large, the details so overwhelming, they feel like paintings of Hieronymus Bosch with a slightly less surreal accumulation of minutiae. These immense tensions are what make Heffernan’s works so current. These are projections of herself, as citizen of our century, America on the sharp edge of financial and militaristic empire, a globe on the verge of environmental collapse. In short, the readings of environmental concerns and allusions to the contradictions of globalization seem entirely apt.

{Millenium Burial Mound | 2012

Oil on canvas | 68x 80 inches}

As an example, in Millennium Burial Mound, wolves and other predators break forward into the painting and the foreground over a shoddy fence that limits their movement through space, as we increasingly see with diasporic communities and the fenced borders around the globe. And though Heffernan is conscious, both in her works and in our interview, to distance herself from a critique of consumerism, she’s perfectly fine discussing the other two large issues of environmental degradation and globalized society.

She emphasizes, “We can’t support it. We are so clearly on a cusp, and I feel it viscerally in a way I would never have anticipated. It’s a factor of your sensitivity extending out beyond your own bloodlines, through your kids, out into your community and even further out into the world. It’s clear to me, even though it’s a bit of a sky-is-falling, Chicken Little trope, an end-times kind of cliché, that any talents I had to say something, I had to use.

“This is the largest conversation of our time. I’m constantly flummoxed—as artists are the nerve center of a culture—and I’m just wondering why everyone isn’t on this, like we were in the ‘60s to end the war. It seems so urgent.”

“It” for Heffernan is both our environmental condition and the logic that predicates this condition, the uneasy acknowledgement and urgent silence of the media sphere. Within the world of her paintings, her subjectivity, Heffernan is an everywoman of sorts. Her inner thoughts and ideas become projections and gestures that seek to move beyond her singular experience. However, Heffernan is also, quite simply, an artist attempting to represent her socially conditioned mindscape.

“I simply paint what appears to me,” she says, “and I realize later the communion between what I’m doing intuitively and then what turns out to have been happening in my body that I wasn’t even thinking I was addressing.

“The thing I love about painting is that it’s an encounter with another being, via their touch. They’re gone from the room, their painting is left on the wall, and you can feel their touch in it.”

If this is Heffernan’s version of success, then she’s accomplished it. There’s no doubt that in her exhibit, Sky Is Falling, there’s a sensual encounter with the qualities of Julie Heffernan, and therefore the greater world around us, rooted in experience, bodies and touch.

{Self-Portrait as Explosive | Year: 2011 | Medium: Oil on canvas | Dimensions: 62 x 68 inches}

Sky is Falling: Paintings by Julie Heffernan is on view at the Crocker Art Museum (216 O St.) until Jan. 26, 2014. Visit Crockerartmuseum.org for more info. Drop by on Jan. 26 from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. to meet Heffernan and hear about her works directly from the artist.

Olly Murs and Bonnie McKee

Assembly, Sacramento • Friday, Sept. 27, 2013

There are two paths to pop stardom: one is to work your ass off until you bottom out or break out; the other is to miraculously land that fat, major label contract and let the industry do its work from there. These possibilities are represented by the trajectories of Bonnie McKee and Olly Murs, respectively, both of whom just blew the minds of a few hundred pop fans and/or tweens Friday night at Assembly—suddenly, under new management.

Likely, you’ve never heard of either of them. Olly Murs has a soulful voice and, according to Wikipedia, a signature “Olly wiggle.” He killed the competition in season six of The X-Factor in the United Kingdom. He’s white, handsome and wholesome; he speaks with an accent, sings without it. He’s everything that a program centered around monetizing the lugubrious task of talent scouting, (i.e. getting advertisers to fund through branding, product placement and commercials what was previously an expensive and labor-intensive part of the music industry) would want. His top hit stateside, “Troublemaker” featuring Flo Rida, is getting regular Top 40 play, but we love him because Chiddy Bang appears on “Heart Skips a Beat.” Murs has three albums, is a double-platinum selling artist in the United Kingdom, and for our purposes here, he’s the dude who suddenly hit the big time and, “ba da ba da bum,” he’s loving it (see what I did there?).

Then there’s the pop-protestant work aesthetic, as represented by Bonnie McKee. Yet initially, her story is one of those jackpot, major label narratives. She hit Los Angeles and had a contract with Reprise Records at the ripe young age of 16. She released her first full-length, Trouble, in 2004, and was dropped after she stabbed her CD to a tree in a label exec’s front yard. For that, she got the wrong kind of attention. This was her bust point.

But McKee stuck around, did some paid songwriting gigs, and by 2013, she’d accumulated a series of awards and hit singles. Her songwriting helped define 2010 with a combination of Taio Cruz’s “Dynamite” and, far more importantly, Katy Perry’s “California Gurls” featuring Snoop Dogg (or Snoop Lion?). She was a part of the three best tracks on Perry’s Teenage Dream (I know! They’re all so good! How could we judge them?), the other two being “Teenage Dream” and “Last Friday Night.” Since then, McKee’s worked with, among others, Nicole Scherzinger, Kelly Clarkson, Britney Spears, Miranda Cosgrove, Christina Aguilera, Carly Rae Jepsen, Ke$ha, Rita Ora, Ellie Goulding and fucking Cher!

All of this is to say, McKee has made it, whether she becomes a successful solo artist or not. She’s put the work in, she’s got her name on the liner notes, she’s got the awards in her closet.

But isn’t this a concert review?

Yes, but there’s a reason this review sounds more like a press release. That’s because this wasn’t a concert exactly. It was more of a trial run, a practice lap, a full dress rehearsal. Actually, it felt like watching a guest appearance on The X Factor. “Here’s what they’ve done; now see them live!”

So, we showed up to catch the set up for Bonnie McKee. Then there she was, red hair shining in the stage lighting, clips of her music video playing in the background, her fingers gracing the keyboard. The only other person on stage was a guitarist for accompaniment. However, her opening number was something I expected to hear from Super Mash Brothers, not this reformed singer/songwriter turned pop-star-to-be. She performed charismatically a collage of her best charting singles, starting with “Teenage Dream,” then “Dynamite”; “Last Friday Night,” then “Part of Me”; Ke$ha’s “C’Mon,” then “California Gurls”; “Wide Awake,” and then “Roar”—all the hooks subtly arranged so that every FM-radio-head could sing or scream aloud as our collective hearts desired. It was a strange thing to begin with, had it not been for what followed.

McKee began another song that I can’t recall as I was attempting, and failing, to be a photographer. Then I ran up front as she began her current radio single, “American Girl” (you’ll note that California Girl is sort of already taken). I shouldered past the tweens crowding the stage, who literally pushed me when I tried to leave, and got some mediocre photos of McKee dancing. It was rehearsed and simple, but it worked. There weren’t any fireworks or glitter, but the kids liked it, instinctively. And then she was done.

That was it. Three and out. I was heartbroken.

They set up the stage for Olly Murs, he performed his abbreviated set, made some jokes about being back in America, mentioned that he loved touring with One Direction, and it was over. His accent was cute, his voice was in key, his two backup singers harmonized.

Yet this was the weird thing about this concert. It just seemed like a quick exhibition. There were no musicians on stage, McKee’s opening “song” aside, and everything was tracked on a disc or hard drive somewhere off stage. One large LED screen constantly told us who was playing, as though we might confuse the performers with themselves in this austere setting. The young girls screamed at Murs, and my friend said to me, “I’ve never been to a Beatles show before.” Sadly, that was the highlight. So if this reads like a press release, that’s because this show felt like one.

Paper Pistols’ Deliver Us From Chemicals examines life in the new age

It’s 2013: NASA is collecting applications for Mars colonists; international, state and local governments continue to gut social programs and education through austerity measures; and California, despite its drastic cuts, projects a minimum $1.2 billion dollar budget surplus for 2013. As I write, the still hot ashes of the Egyptian Revolution are igniting a populist uprising in Turkey. This month, according to major media, suicide is an epidemic. The world is lonely, the global economy is stagnant and in an effort to grow, we’re colonizing space; everywhere—Arrested Development season 4 included—it’s austerity and decadence, riot and romance.

“I’m just here in my body,” sings Julie Lydell on “Oil,” the first track of Paper Pistol’s debut album, Deliver Us from Chemicals, “No weight on my chest/No knot in my throat/Unimpaired by the impulse to make sense/of senseless things/patterns and chaos/God, I’m tired/and I’m sick/of caring about where all this is going.”

Lydell’s voice, slightly nasal and rich in timbre, contains our moment today: the anxious present, the absent future. True to pop form, Lydell locates herself as a body, anywhere and everywhere. The lyric I, here, is alone swimming in gin and existential crisis at the bar, walking the streets of Turkey surrounded by neighbors and teargas, discarding consequence, guilt, frustration and concern.

This chorus increases via the layers of samples, melodies and instrumentation before falling to the austere, the minimalism of Ira Skinner’s rim-shots over a pitter-patter series of electronic clicks. As a song, “Oil” utilizes a Thom Yorke-ish intro, syncopations and percussive pops that sound like a digitized steam engine gathering speed—a tenacity realized by Skinner’s rolling-stop snare work at the end of the track. And during this large arc, the cycle, the song structure builds. This next verse section, a series of piano driven chords, highlights Lydell’s addition to Skinner’s one-time solo project.

“I don’t know any prophets,” sings Lydell, “Don’t ask me for my oil/That lamps been burnt out for so long/I’ve no more light to give.” The play here, as in many other places on the album is a skipping of connotations. From the inability to see the future to the non-existent incentive to invest in it, Lydell and Skinner, in a combination of ups and downs, replicate the cyclical feeling of a bubble bust economy, all dwindling resources and antiquated infrastructure. For this, the album is an emotive, LED beacon in our dimly lit times.

This is not to say it’s anything other than music pushing its boundaries both lyrically and technologically, as Lydell and Skinner are quick to point out.

“This is where music is going now,” states Lydell. “It’s crazy how many frontiers are being expanded. We can almost make music on accident with an app or something.”

With this development of computerized production there’s also a tension that emerges between the traditional role of performers and machines. Lydell understands this as an opening of potentials: “I don’t think you can lose the organic side of it, absolutely never. You can augment or improve on what you would be able to do with the bodies, with instruments.”

“It’s like limitless capabilities,” confirms Skinner, “when you’re playing electronically. We could go up there and just play piano and drums, but why be limited by how many people can touch an instrument? We physically play most of the parts on the record and play them off the laptop live because there are not six of us.” Then he adds, “I think we have trust issues as well.”

Despite the meager numbers, Paper Pistols is a dominant force live. They concentrate on making their concert performances engaging and entertaining.

“We can still be a dynamic band, not sound robotic or fake,” explains Skinner.

“I think there’s such an energy live. There’s a lot of energy on stage—presence. Because of that, most people don’t think, oh shit, half the music’s on a laptop. It’s not like we’re doing anything super unusual for these times. All bands have laptops in their bands now. Ten years ago when I started Evening Episode, that was unheard of. It was a challenge. We had adapters hooked up to adapters just to make it work.

“I don’t think I’ve ever been onstage where I’ve half-assed my performance,” Skinner continues. “For me, it’s a very therapeutic release. It’s such an outlet, and every show I try to push it more. I write my parts based on emotion, parts that feel cool.”

Writing, practicing and performing are vital for both Skinner and Lydell. Lydell even jokes that her daily stress about and frustration with the world dissipates after a good practice session or show.

These concerns, likewise, find expression in the album itself as a conflict between isolation and community, absence and presence. “I think that’s the theme of the record,” Lydell meditates in a sprawling thought, mirroring our complicated contemporary. “It’s hard to have an electronic album and have it be about getting back to this primitive state, or this more pure place, before the world was full of billboards and Internet homepages and anti-depressants, nicotine, alcohol. All the things we can use to escape from ever having to deal with selfhood because it’s really lonely. I think lyrically and thematically, that is the tension this postmodern world promises.

“When people used to be alone, they were truly alone,” she adds. “There was no way to communicate unless there were other people [physically present]. You had to be comfortable being by yourself. [Today] you can focus on your projected self because you can just do it constantly; what do I want to put in this status update so that people can see that I’m having an existentialist crisis and I need to solve it? You don’t have to ever deal with anything if you don’t want to. Or you can take a pill.”

These constant bombardments and over-simplified alleviations express themselves lyrically and sonically on the album. If Lydell drifts as a lyricist between loneliness and connection, then the minimalist verse structures and rich, decadent hooks similarly materialize these concerns through chords and melodies. The album has many moments of quiet tension and multilayered movements.

Lydell sees the work as a collaboration of sorts between opposing forces: “Ira and I have different composing styles. I really like tension. I think there are moments on the album where it’s really decadent, kind of luscious because of how much is going on; epic. Ira’s written film scores.”

“That’s my part,” Skinner states flatly, his stoic front confirmed by his casually crossed arms, smooth-shorn scalp, burled beard and deep voice. “I specialize in epic.”

Next to him, Lydell seems a bit more dynamic despite her “logical, monotone” self-description. She slouches back sipping tea in black and white wing tips, a long dress and sleeveless denim jacket. Both members casually detail what they hope to accomplish in the next year, which includes finding a manager and setting out on a small tour. Familiar friends, they joke quickly between each other. Their chemistry confirms the band’s back-story: Lydell canceled a return to Austin, Texas, to continue working with Skinner on Paper Pistols, alongside her other musical projects. Thus, the album came to be.

Describing how Paper Pistols came to be in its current incarnation, Skinner, who spends most days recording bands in his Midtown studio or running sound for various local venues, recounts, “After The Evening Episode, I didn’t have a desire to do a band again. I’d need to get a van, a practice space, book tours. It didn’t seem fun to do that again. Playing music with Julie has changed my perspective. It’s inspired me to actually start writing music. It’s an easier process with her because she moves quicker than I do, and she’s got so much energy. It’s different in a very positive way. ‘Astronaut Food,’ we wrote that and recorded it in a day. It sums up the record and so many of Julie’s views on the world. It’s a lonely ass song, too.”

“It’s just The Lion King. In a key too low for me,” smirks Lydell.

“Does that make me Simba?” asks Skinner.

“It does. And I’m still myself,” Lydell quips in return.

Aptly, for both musicians, “Astronaut Food” is an anthem of sorts. Over a music box sample and long sustained piano chords, Lydell sings, “The future looms not as bright for the most of us.” The final crescendo of the song is a surge of booming toms where Lydell repeats in a melancholic affirmation, containing hope and despair, “Deliver us from chemicals.” The song concludes with a four-part, gospel-style harmony that, in a song about literally being isolated above earth, desperately seeks transcendence.

Lydell explains the song, the possibility of a future, as a “conflation of living in the age of celebrity where everyone wants to have something special, look rich. But really we’re underemployed, making $9 an hour. There’s this gap. I think we’re really removed from reality in some ways, and it’s showing up on a bigger scale post-2008. There are so many complex systems, and I can’t even fathom it.”

The future looks similar to Skinner, a monoculture of sorts: “My realm of expertise would be the music business. If you listen to today’s radio, no, we don’t have a future, or at least not a very bright one. The influence that pop musicians have on the youth, artistic or not, it’s not positive. But, I think that’s because I’m old. People who are produced now don’t have an artform.”

Ultimately it’s clear that both Skinner and Lydell would prefer to stay on Earth playing music despite the chaos that surrounds us.

“I wouldn’t fucking go out in space,” Lydell laughs. “I would kill myself first. It freaks me out. I want no part of it. I’ll cling to a tree.”

“They have that thing right now,” says Skinner, regarding Mars. “You can sign up, but you can never go home. You live in a bubble. Who would do that?”

“People who like Burning Man would go. That would be my worst nightmare,” says Lydell.

“That’s what they should do,” concludes Skinner, “dump the Burning Man tickets and send them to Mars. I’m done with some Burning Man shit.”

There it is. Mars, loneliness, anxiety, austerity, decadence: Paper Pistols, Deliver Us From Chemicals, 2013. Transcendence, indeed.

Catch Paper Pistols live on Saturday, June 22 at Davis Music Fest’s City Tavern Stage at 9 p.m. They are also scheduled to play Launch Music Festival, a two-day event going down on Sept. 7 & 8 at Cesar Chavez Plaza. Visit Launch’s website for tickets!

The Gillilands celebrate their 10th anniversary by giving back to the city that has given them so much

Words by Joe Atkins • Photos by Nicholas Wray

Nestled neatly on that delicate transition between downtown and Midtown, Lucca Restaurant and Bar is already, as of our print date, halfway done celebrating a decade of success. Longtime restaurant workers, the Gillilands, opened Lucca with two paintings and an idea: large plates with locally farmed food.

The blue goose and the red bull still hang on the walls of Lucca today, and the aspirations of locally sourced meats and produce has inspired the Gillilands to open Lucky Dog Ranch in Dixon, Calif., producing pasture-raised beef. While this holistic vision might not seem all that original in today’s farmers market, farm-to-fork atmosphere, it is worth noting that this wasn’t always the case. No one wants to admit that they’re sacrificing quality for price, but this is a primary obstacle for restaurants. And not all wind up making the right decisions. The Gillilands have been able to sustain their vision with Lucca, open the equally successful Roxy Restaurant and raise their own cattle to supply their restaurants and others, and this speaks volumes.

Lucca is successful, hands down, but Terri Gilliland is quick to note they’ve been successful because of Sacramento. “We’re so grateful to be at this point,” says Gilliland. “We’ve weathered it all, especially the last five years. We’re incredibly grateful to the Sacramento community for the support.”

It’s clear that Terri enjoys being a restaurateur, in all its capacities. Before our interview begins, she lets me know that she has to travel to the family ranch in Dixon to aid some of the newborn calves—Terri serves as the de facto caretaker for new calf additions at Lucky Dog Ranch. One employee even told me in passing that it can be trouble, because once she’s named them, they’re no longer available for slaughter.

It’s this sort of devotion, not only to their livestock but to the details of their restaurants that have made the Gillilands, and Lucca in specific, profitable. “We got off to a great start,” explains Terri. “We had a lot of community support and friends.” She contributes the early success of Lucca to three factors: “Ron and I were experienced restaurant people; we’ve worked all aspects of restaurants. We have an exceptional group of people at our restaurants, especially our management. They walk the walk. And we were embraced by Sacramento.”

Over the last 10 years the Gillilands have fostered many relationships, the most famous being ex-governor Arnold Schwarzenegger. While the Governator did have a large influence on their early success—many cigars have been smoked on their back patio—this relationship is not the most important. Terri mentions a boy who decided to celebrate his eighth birthday at Lucca, and his family has returned every year since. Terri mentions a couple who had their first date, their wedding and their child’s baptism all at Lucca. On rare occasion, Terri and her husband Ron will even hug patrons, mistaking them for friends.

“We’re both really affectionate people,” she laughs.

But when we talk about restaurants, what actually matters is food. This brings us to head chef, Ian MacBride, who has been at Lucca for seven years, shopping local markets, planning salads and entrées, plating dishes. Thinking about it, as a local, I can say that Lucca is unexpectedly one of the restaurants I’ve most frequented in the last six years, meaning MacBride has overseen a significant amount of my meals. And I’m sure I’m not alone. As MacBride states, “On a good Saturday, we’re putting out 500 dinners.”

That’s a lot of entrées, yet Lucca faces different obstacles in today’s economy. “There are so many more seats, and not necessarily that many more people downtown,” says MacBride, quick to list a handful of restaurants that have both opened and closed in the last seven years. The pivotal economic shift in 2008 brought a new set of challenges to the existing restaurant scene. “The dinners are the same,” says MacBride, “the lunches have slowed.” He points out that even the traditional high-end eateries have done most anything possible to lure more customers during the day. In 2013, even Ella has a happy hour.

Looking over Lucca’s menu, I think I’ve had almost every item, stealing bites from friends and family, as I’m wont to do. Lucca’s zucchini chips are my favorite appetizers in Sacramento. But until my most recent visit, I’d never tried the Lucky Dog Ranch hamburger, with cheese. This burger comes undecorated, with the accompaniments on the side: pickles, onions, lettuce, tomato. The produce is fresh, and the fries are nicely seasoned with a touch of salt, but the patty is unique. It doesn’t have that greasy, fat dripping everywhere quality so inescapable in most burgers. The meat is cooked nicely with just a touch of pink showing, and the seasoning doesn’t overpower the actual taste of beef. Clearly the burger is thought out from top to bottom, and for that alone I’d recommend it. Especially paired with a nice Ruhstaller 1881 Amber Ale.

The other surprise from my visit: roasted beet and citrus Salad. The bed of baby kale with olives, almonds, and ricotta, gives the beets a complimentary pairing. The beets themselves are smoky and sweet, and the flavor is rounded out with a coriander citronette, a dressing made of olive oil and lemon. If you’re a fan of beets, this is a must try dish. Likewise, the cheese flatbread with chickpea hummus, olive tapenade, and red pepper romesco, will disappear from one’s table immediately. These two small dishes couple together nicely. Also, for the more adventurous, Lucca might have the best escargot puff pastry in town, when it’s available.

For dinner, I’m a fan of Lucca’s spicy sausage. The Spicy Penne, with baby artichokes, olives, capers, roasted tomato, garlic, chili flakes and sausage; or the Paparadelle, with said spicy sausage and mushroom ragu, are both highly recommended. The pork chop with apple and dried cherry chutney is always rewarding. It’s moist, flavorful, and the apples and cherries provide a delicious sweetness to this entrée.

While I’ve never had a bad experience at Lucca, I’d describe the restaurant as good, specifically consistent, but not quite excellent. This seems to be the general consensus from my community as well. The atmosphere is open and inviting, the lighting well placed, the patio inviting, the bar easygoing and conversational. There’s no specific quality that seems to be lacking exactly. Lucca does what it’s been doing for the last 10 years well. While it’s not always the restaurant that pops to mind when we’re looking for a bite, it’s never disappointing.

It’s also clear that both Terri and head chef MacBride are conscious of this to some degree. In passing Terri mentions that it’s good to just realize what the restaurant is, what its strengths are and figure out how to take advantage of those in pursuing growth. MacBride is excited about the upcoming anniversary events, where he will show off all new items, moving completely away from the staples of Lucca’s menu.

It is, after all a celebration, as MacBride notes, “The 10th year is a benchmark. You know you’re doing something right.”

And owner Terri Gilliland is happy to give back to the city that has so long supported her restaurant: “We want to make a small contribution back to the community.”

For the next two Wednesdays, Lucca will be hosting the final pair of 10 year anniversary events, the previous two benefitting Verge Center for the Arts and Mustard Seed Spin.

On April 17, MacBride will reveal his “Eating Like a Kid Again” menu, and guests will enjoy a recycled fashion show; the proceeds for this event will benefit Sacramento Children’s Home. On April 24, the five-course fixed menu will have a farmers market focus, emphasizing locally sourced edibles; proceeds will be donated to Sacramento Farm-to-Fork. Both dinners start at 5:30 p.m., and seating is limited but available.

15 Years, 11 Tracks, 11 Vocalists, 2 Bandmates: Tel Cairo

Words by Joe Atkins

For the last 15 years Cameron Others and 7evin have been working on their material, laying out beats, loops, archaic recordings of bedroom beatbox compilations and reworking that material into new orchestrations. In the last two years it’s all come together, and now, as Tel Cairo, Cameron and 7evin are set to release their debut full length, Voice of Reason. The album itself has been part of the long process of self-discovery for these two electronic musicians. Their sound, their relationship to composition, their knowledge of technique and technology have increased with each singular endeavor, and the result is a precision track listing of rattling low-end bass and twinkling high-end melodies.

And I’ve yet to mention what, for me, is the most impressive part of the album: its list of local MCs and vocalists who dominate the lyric and lead portions on the majority of the project. It’s a list of past, present and future Sacramento stars, artists whom have been working the scene for the last two decades trying to lift the city up with their own talents and careers. There are individual appearances from Aurora Love, “This Is Not”; Agustus thElephant, “Music Box”; and Mic Jordan, “Electro Knock.” On “Twelve Paths Toward Movement,” Sister Crayon frontwoman, Terra Lopez appears alongside hip-hop local TAIS; Mahtie Bush spits verse after verse on the track “Illicit” and the unknown, yet powerful, Stephanie Barber holds down the hook. Lest we find ourselves stuck in the lady sings the hook cliché, Paper Pistols new lead, Juliana Lydell sings the verses to the high pitched chorus of Caleb Heinze, from Ape Machine and Confederate Whiskey; and Task1ne, Voltron reference and all, flows over the verses of “Evening Push,” before local legend Jonah Matranga gives his signature falsetto to the hook. It’s a list that’s both diverse and impressive, and it makes for an album that highlights the many dynamic qualities of music in Sacramento.

Breaking from some highly competitive Wii, 7evin and Cameron sat down with Submerge, and we talked about Sacramento, influences, genre, processes of songwriting and recording, skateboarding, musicianship, Ira Skinner’s beard and the talented slew of lyricists they worked with on the album. In addition, Submerge exchanged a few emails with the lyricists, and, likewise, we share their thoughts on working with Tel Cairo.

What brought you to Sacramento? What are the best and worst parts about this city?

7evin: I moved here about eight years ago to work with Ira Skinner, a good longtime friend. Sacramento has an amazing group of musically talented individuals. We like what’s going on here. The cost of living is amazing; you don’t have to feel so pressured. The bad part is that there is almost no monetary value for art here.

Can you describe your songwriting process?

7evin: A lot of times we start off with analog, a guitar, drumset, bass. We get in there and start doing electronics. We don’t do samples. We do our own tones and MIDI controlling. There’s always one part, and we shoot it to the next person until he can’t work on it anymore, and he shoots it back. We’ll meet once a week and we’ll work on that song. We made 32 tracks for this album and 11 made the cut.

What sort of influence did Ira Skinner have, working with him as a producer?

Cameron: Ira let us figure out who we were. He took all the things we’d been layering for so long, and we’d forgotten what we started out with, and made them sound amazing. Some of these things were already done. We’d put so much into it. We needed to step away a little bit.

7evin: He is so chill in the studio. He let us fumble around to find a niche, and the second he hears something that’s good, he’s like “Wait, go back! Let’s do that.” We have the first word, bounce it off to someone in collaboration; we get the second word, and Ira comes in; and we get the final word.

Cameron: In between there was also a lot of growth and learning on our side, with the programs.

Of the two of you, who’s the biggest perfectionist?

7evin: We’re never happy with it.

Art is never done. We just move onto another song.

Cameron: We look at things a little differently. I’ll hear things differently that he might not hear. Technically, I think he’s the perfectionist, making sure everything is lined up. I’ve tried to watch, and I’ll fall asleep for a little bit.

7evin: We tag team it, recording. I’m 20 percent deaf in my left ear. I don’t hear high end, I hear mid-tone and bass. You can see that and feel that live. [Cameron will] come in and stick this melody here. He brings the beauty to my dirtiness. I’m a gutter-punk; this guy comes in, and he’s playing 12-string guitar. We’re very similar but we’re like the Alice in Wonderland, Looking Glass Mirror versions of each other.

Cameron: We get inspired at the same time from different things. We get a feeling. It could be DJ Shadow, it could be anything, a country song; our creative juices start, and we just sit down and see what comes out. When we work together we balance each other’s ideas.

I know that every collaborator brings a different set of skills to the studio, the songwriting process. Who impressed you most while recording?

7evin: Mic Jordan is one of the smartest people in the world. He’s brilliant. Just kicking it, he’d expand our minds in so many ways. When he came in, we worked an experimental song; it’s not a typical hip-hop track. He rose to the occasion.

He has like four different cadences, and it’s beautiful.

Cameron: Jordan, for sure. Caleb [Heinze], I’ve known that dude for a long time, and I knew he could sing. The way he nails that chorus is genius.

7evin: He has a range that no male should have. We weren’t sure what to do with that track “Nirvana,” but Juliana [Lydell] approached it off of his vocal, like the ghost of the guy she lost her virginity to.

What was it like to work with Jonah and everyone else? How’d you get them to collaborate on the album?

7evin: They were all our friends, except for Jonah, though Jonah’s now friends and family. Jonah’s someone we looked up to, someone we’d seen as kids growing up, going to shows at the Cattle Club. We had mutual friends so I hit him up.

Cam sent over “Evening Push” and he just ran with it. He was so kind and gentle of a person to work with two guys he didn’t know. We sent a lot of emails backwards and forwards. We haven’t got a chance to do it live with him as far as performance. But we’re doing that on April 4, everyone on the album is performing. It’s never going to happen again. It’s like one shot.

We definitely took a Gorillaz approach with this. Terra [Lopez and Cameron] are damn near best friends. I knew Stephanie [Barber] from helping her and her sister with their restaurant, and that girl can sing. We locked her and [Mahtie] Bush in my bedroom with us, and it was like a Seven Minutes in Heaven kind of thing, writing a song on an SM58 microphone.

Stephanie Barber [who is quietly present during most of the interview]: It was really creepy and productive.

One of the ways I’d describe your sound is electric, post-grunge, skateboard culture, all grown up. You happy with that?

Cameron: I’m cool with that. That’s what I do every day, [skate]. Skate videos have helped me listen to different things. In old Toy Machine videos, Ed Templeton uses a lot of Sonic Youth. I watched them hundreds of times. It made me want to experiment with my own guitar.

Would you say your music belongs as the soundtrack to the cinematic build up of a riot or the post-riot moment of optimistic melancholia, where a new world briefly exists but won’t last over time?

7evin: Afterwards, definitely. After everything’s been destroyed, and we’re rebuilding. There’s healing process in these songs. There’s hope. Your heart gets demolished, but you can grow and

move on.

Tel Cairo will celebrate the release of Voice of Reason at Midtown BarFly, 1119 21st Street in Sacramento, on April 4, 2013. This will be perhaps your only chance to see 7evin and Cameron Others share the stage with all of the vocalists who appeared on the album. For more info on the show, go to https://www.facebook.com/telcairo, or hop over to Midtown BarFly’s Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/MidtownBarFly.

4 Questions with Mic Jordan, Mahtie Bush, Task1ne and Juliana Lydell!

How was it to work with 7evin and Cameron on your track?

Mic Jordan: They played me a skeletal version of the song they wanted me on and set me loose with no real guidelines. I definitely had input into its final outcome, but I also felt like, “OK, everybody here knows what they’re doing, they trust me do my thing lyrically, so I trust them to do their thing sonically.”

Juliana Lydell: They’re really open-minded, supportive, and enthusiastic. Creating with them is a lot of fun.

Can you tell me about the process, e.g. did they have the song done and let you do vocals over it, or was it more of a collaborative process where you aided in the musical composition?

Task1ne: They trusted my expertise and let me just record the track like how I usually do it with no problems. It was a blast. I fell in love with the track instantly. I’m a fan of all types of music, so it was great to get to experiment on something different.

Mahtie Bush: They built the track right on the spot, and as they did that I was writing to the beat. It just happened; we were on the same page. The vibe was ill.

What makes Tel Cairo vital to the local scene?

Mic Jordan: The fact that they are bridging the (artificially separated) electronic, alternative and hip-hop communities. Ultimately, what sets Tel Cairo apart is the fact that their music defies easy categorization while somehow sounding authentic no matter what territory it’s venturing into.

Juliana Lydell: How excited they are, how much they believe in community, and what a team effort they make out of the act of creation. They think big. It’s contagious.

How long until Tel Cairo achieves world domination?

Mic Jordan: Who’s to say they haven’t already?

Task1ne: A better question is, which one is Pinky and which one is the Brain? Inquiring minds would like to know.

Hook & Ladder Manufacturing Company

1630 S Street – Sacramento

In 2003 Kimio Bazett and Jon Modrow bought the Golden Bear, settled in Sacramento and committed to making this town a better place. Now they’ve embarked upon a new enterprise: Hook and Ladder Manufacturing Company, a restaurant and bar focused on highly refined eats and attentively detailed drinks, occupying the arched tin hull of what used to be Hangar 17. Yet, while the exterior might be the same, the interior is anything but.

What used to be a dark-ceilinged, neon blue clash of grays and polished, metallic tables, has become a warm, light, playful take on the current repurposed industrial loft aesthetic. The entrance strikes one with votive candles placed neatly around a detailed yet happenstance slat wood wall display behind the host stand. The bar is stocked to the ceiling with liquor, and at its center sits the yeti draft, an upside down tap system that cools the brewed beverages as they travel down the line, gathering a layer of condensed ice on the exterior of the mount.

Bar manager Chris Tucker took a few minutes to explain a few of the finer points of their intriguing bar setup, which includes the yeti system, the keg wine pressurized with nitrogen and the cocktails on tap. Wait, what?

Yes.

Draft wine and cocktails.

Tucker, who cut his teeth in this industry at America Live back in the day, detailed how they craft these specialty cocktails, mix them in huge batches, have them pressurized and then pour them over ice to quickly chill before they’re served to thirsty customers. It’s an intriguing process that we had to try. The four options included a Jameson Stinger, a Negroni with a nice anise finish, a Norse by Northwest with Aquavit from Portland and a Jerry Thomas Manhattan.

Of the four, the first and the last impressed us the most. Like much of the décor of Hook and Ladder, these cocktails are both old and new. The Jameson Stinger is a play on a classic libation with a nice balance of mint and Jameson that came off both refreshingly simple and flavorful in texture. The Jerry Thomas Manhattan differs from the traditional Manhattan. It’s crafted with Rye whiskey and Luxardo, an Italian maraschino cherry liquor, vermouth and bitters, garnished with a lemon peel that has the Hook and Ladder logo branded upon it. I also really enjoyed the Templeton rye and house made ginger beer, which had a sweet, light kick.

Oh yeah, and there are eats.

We had two meals at Hook and Ladder: one lunch, one dinner. Between the two meals we sampled multiple starters, a salad, a pizza, a sandwich, a cheese plate and an entrée. The starters were impressive by themselves, revealing an attention to quality ingredients and presentation. The three-cheese plate consisted of an Italian Tallegio, a brie-like texture that spread smoothly on the toasted bread it was served with; a Dutch Beemster with mustard seeds; and a Californian Carmody. Each paired well with the almonds, olives, persimmons and house dried fruit plated alongside it. The smoked eggplant baba ganoush topped with goat cheese had a rich texture that complimented the garlic-roasted flatbread. The seasoning of this pairing had a peppery kick that made me come back for more. The trio of sausages, which included a spicy chicken chorizo and a lamb link, served with mustard and two different chutneys, surprised with their quality. The sausages are all made in house, ground and stuffed, and then they’re cooked in beer before being oven-finished for service.

However, despite all these smaller plates, the highlights of our lunch experience were the two large plates: the sweet potato pappardelle with mixed mushroom ragù, shaved sheep’s milk cheese; and the barbecue chicken sandwich served with potato chips inside–Liz Lemon style–and a side of fries or salad. We opted for the fries and were happy about the decision. We split the sandwich and it disappeared immediately. The house barbecue and slaw were nicely chosen for this dish. The barbecue sauce had a sweet taste that was aided by the salty potato chips and the moist fried breast and thigh meat. The Bella Bru steak roll finished the entire piece.

All of Hook and Ladder’s pastas are made in house, and the sweet potato pappardelle did not disappoint. There are two types of pasta noodle dishes that I tend to find within our local cuisine. The first is a noodle type dish with a light oil toss and varied seasonal flavors, and the second focuses on the pasta as a base for a rich, hearty sauce with a depth of taste. The sweet potato papparadelle walked a nice line between the two. The mushroom ragù and sheep’s milk cheese brought a soft and thick baseline, but each bite felt light on the tongue. Over the course of our meal, as I sampled other items, this was the dish I kept repeatedly coming back to.

During lunch the clientele was relaxed, small groups, with others grabbing a quick bite at the bar. But dinner seemed like a livelier group. Larger parties laughed aloud in the warm yellow light, and the room felt like it was alive with the murmur of multiple conversations. It was, after all, Friday night, and Hook and Ladder was apparently doing well; we had to sit outside because by 6 p.m. table service inside was booked up for the night.

Like the interior, the outside impressed. Repurposed tabletops fit together–with heat lamps for the winter months–under a high awning, and warehouse flats lined the previous fencing, supporting sheet-metal gutters with freshly planted succulents and ferns inside.

We started with the Yukon gold potato, crimini mushroom, rosemary and crescenza pizza, based on the waiter’s recommendation. Hook and Ladder’s head chef is Brian Mizner, who held down Hot Italian when it first opened, and this made sense when the pizza arrived. The dough is similar to Hot Italian’s, but the pizza’s ingredients make it unique to Hook and Ladder. The potatoes were seasoned and soft to go along with the light dusting of crescenza cheese. The mushrooms and rosemary rounded out the taste, and we were quite happy with two slices each as an appetizer of sorts and saving leftovers for the next day.

The pancetta and poached duck egg salad had a variety of texture and balance. The mix of frisée, radicchio and greens allowed a hint of bitter and woody to mix with the salty punch of the small pieces of pancetta. The duck egg and vinaigrette dressing gave more depth, and even a hint of sweetness, to this salad.

Lastly, we ordered the bacon-wrapped pork tenderloin medium rare to finish our meal. This entrée is served on a base of braised nettles, cut into medallions, and topped with Gorgonzola gnocchi. The tenderloin itself was moist and had a light flavor supplemented by the bacon. There was a bit of sweetness from a bit of sauté, and when followed with the Gorgonzola gnocchi, this plate was quite satisfying. The braised nettles provided a mild contrast to these rich flavors with a crunchy, slight bitter bite.

Ultimately, Hook and Ladder is a fine dining establishment that I’m sure will find success. While it’s only been open for seven weeks, it’s obvious that this restaurant and bar will only get better with time. During the summer, it’s going to be hard to find a seat most nights of the week. For those interested in just a drink or two, there’s ample seating at the long bar covering the west side of the building, a waiting area with tables made from old school board games such as Sorry where couples can enjoy a cocktail, perhaps before dinner.

It’s clear that Bazett and Modrow have put a lot of thought into this enterprise. They’re looking to make Sacramento a better place, and it is, after all, worthy. Anyone visiting the Golden Bear over the last nine years and watching it change should see the logic in Hook and Ladder. Bazett and Modrow want to move from bar-restaurant to restaurant-bar. For those ready to shift gears a bit from those late night Bear experiences to a quality meal and the nuance of a consistent bar, Bazett and Modrow have one option to add to Sacramento’s restaurant list: Hook and Ladder Manufacturing Company.

Sacramento artist taps into a childhood obsession for his latest show

Pop art in the ‘60s and a growing critique of consumer culture at the end of modernism led art into an aesthetic of mash ups, parodies and pastiche. Pulp art, comic books, baseball cards and the developments of global branding strategies all collided into Wacky Packs, a series of stickers that mocked consumer goods through parody, produced by Topps Trading Company in 1967, and originally illustrated by Art Spiegelman (writer/artist of the graphic novel Maus) and Norman Saunders. Fast forward 45 years, the influence of these seemingly benign stickers can be found in the artwork of Bruce Gossett.

Gossett’s works have been seen at a few select galleries around Sacramento and sold at various car shows over the past decade, but his current work draws specifically on the playfulness and base impulses of a childhood fascination: Wacky Packs. His artwork follows this tradition of plagiarism and parody, using existing advertisements and iconography from the custom car world to create tongue-in-cheek fine art works that connect an adult world of masculine custom hot rods with the juvenile playfulness of puns and gore.

Gossett has developed his art over the years working with multiple graphic forms, all of which have influenced his relationship to the canvas, his preferred medium. He’s printed T-shirts, rock and car show posters, stickers and done customized airbrushing and detailing on cars. He once tried his hand at stand-up comedy, only to realize he didn’t like the spotlight and has since found his calling in a small, insulated shed-studio in the back yard of his West Sacramento home. Gossett spent years going up and down California, attending car shows, selling his works: T-shirts, posters, stickers, fine arts. And the influence of this culture has been foundational to his development as a graphic and fine artist.

But it’s not just car culture in general that Gossett finds alluring, it’s a specific subspecies of that broader category, those custom car creators, the seedy underbelly of that combination of Detroit automobiles and California counter culture. This DIY renaissance of the automobile, the material object that transported America from farmlands to urban spaces, appears in the work of Gossett as an image set to be appropriated and employed according to a particular set of aesthetics.

These counter culture references are manifest in his current work, the Speed Equipped series, which will be shown for Second Saturday in October at So-Cal Speed Shop on Del Paso Boulevard. The Speed Equipped show focuses specifically on parodies of logos for hot-rodding companies like Moon Speed Equipment, from which the show takes its name. Gossett has created a set of produce brands with the low-brow humor of those Wacky Packs, and he has even been tapped by Anti-Hero Skateboards and local John Cardiel to create the artwork for a pro-series of decks. Gossett’s works span multiple culture groups and as such he’s a significant contributor in the battle against bourgeois ideals and high-art. He’s a working class artist, and that’s just why we like him.

Tell me about your new show, Speed Equipped.

I was obsessed with Wacky Packs in the ‘70s. They were parodies of national products. You know, household products, Windex and stuff like that. They basically mocked them and made fun of them. They were stickers in chewing gum packs. I remember kids covering their closet doors with them, much to the chagrin of their parents. I got obsessed with them. It was funny. The imagery was so base and crude, like it was painted with a broomstick or something. The humor was just great.

Finally, I thought about it one day, and I’ve never seen parodies of the speed equipment. I’ve always been immersed in the car thing, and I thought why not make fun of the icons of the rod and custom world. It’s something I’ve been working on over a two-year period. I’d like to get them out there and get them seen. I think there’s a generation that grew up in the ‘70s around Wacky Packs, skateboarding, punk, irreverence and that audience totally would get it.

I’m also showing some of my Builders Series. It’s the guys that build cars that I dig, but they’re the new generation of builders as opposed to the old generation. It’s not fair cars and Sunday drives, lawn chairs and car shows. There’s a new generation of builders and hot-rodders and the vast majority of them are coming out of the skateboarding world.

Can you explain how that series is different for you? How it’s a change of direction from your previous work?

The Builders Series is more photo-based. Sometimes it’s the vehicles they build, and I’ll focus on that. Other times I’ll start introducing images of the builder, so it’s a little more personal. It’s difficult, painting portraitures and capturing likenesses. It’s more representational, photo-realistic, but I’m making them psychedelic, lots of drips, lots of maneuvering of the surfaces so that you know it’s a painting as opposed to an airbrushed, photo-realistic work.

What’s the best and worst parts about being an artist?

Being locked in the studio is boring, frankly. There’s nothing more I’d like to do than be in the studio for 10 hours and paint. But by that eighth hour, I’m probably pretty sick of it. The days are weird. There are times when it’s fun; there are times when it’s work. I think I like the beginning and the end best. I like when it hasn’t been touched and I first lay in backgrounds, working from the rear forward. You’re establishing a mood when you first start, so it’s fun. Anything is possible. And in the end, it’s always nice to finish something. You’re happy it’s out of the way.

Once I finish something, I don’t want to look at it for a while. Then a week later I’ll obsess over it for about a week, and then I’m usually pretty good with it. For that reason I always have half a dozen paintings going at any given time.

How do other forms, graphic design, T-shirt printing, etc., influence your work?

These are like complex graphics really. My knowledge and experience over the years from different industries, sign painting, pin-striping, graphic applications for hot rods, on vehicles, I get a lot of influence from those other forms. To produce really clean graphics you work rear forward. Do your infill colors and then hit the black lining. It’s really the cleanest way of producing stuff.

When did you decide to take your artwork seriously?

After about the first year, I took it seriously. I started in 1989. I’ve always designed stuff and did things with paint. We stole Testors paints from Thrifty’s and pay for a ten-cent ice-cream cone, and we’d customize our skateboards. I’ve always been around cars, my family was in the car industry. I wanted to get away from it, so I actually tried my hand at stand-up comedy. That didn’t go real well. Then I took a class at City College, the material was stale but I took to it real easy. I realized not only that I had an aptitude for it, but that I enjoyed it. And I was useless in other areas. I just had a short attention span, and the art thing seemed limitless. It really took off in the mid 90s when I really started pursuing more of a car based or an automotive bend.

What is it about cars and hot rod culture that you find so alluring?